Scary yet humbling. That is how the health care community in India describes its experience of the Covid-19 pandemic that affected more than 80 lakh people and took more than a lakh lives. The novel coronavirus in itself was a challenge, an enigma that kept unravelling at a breathtaking speed. We were clearly unprepared, and it showed—from supply chain disruptions and lack of personal protective equipment and ventilators to staff shortages and exhausted caregivers.

But the crisis forced hospital administrations to come together and rise to the challenge of treating an overwhelming stream of patients. This, while trying to understand the virus, even as routine surgeries and elective procedures got cancelled, leading to a major occupancy drop and significant revenue losses. As public hospitals were converted into Covid-19 centres, patients who depended on them were lost. Unnecessary delays in non-Covid treatments led to a surge of preventable emergencies and non-Covid deaths, thereby compounding the panic.

“The pandemic has been quite a teacher for hospitals and health care institutions across the country,” says Dr Ramesh Bharmal, dean of T.N. Medical College and B.Y.L. Nair Charitable Hospital and director of medical education and major hospitals, Mumbai. “We have learnt our lessons early on and have emerged stronger than ever,” he says. In April, the civic-run hospital got converted into the city’s biggest Covid-19 facility with more than 1,600 beds. Over time, it treated more than 6,000 Covid-19 patients and aided delivery of close to 1,000 babies, born to coronavirus-infected mothers. But the journey was anything but smooth. Heaps of biomedical waste in yellow bags were reportedly seen lying unattended outside its premises. There was an acute shortage of Remdesivir when more than a hundred of its critical patients needed the life-saving drug. Another civic-run hospital faced enormous challenges in disposing of unclaimed dead bodies of Covid-19 patients and acute staff shortages. But these hospitals managed to keep their head above the water.

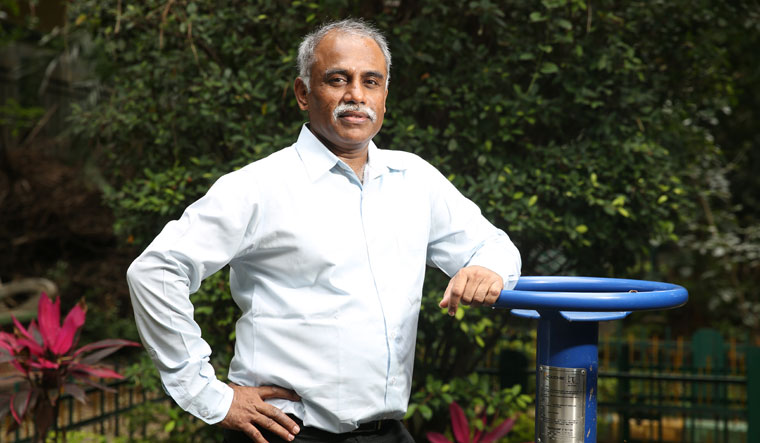

Most hospitals went through the same experience. “Resilience is one of the foremost lessons we learnt through the pandemic,” says Dr K. Hari Prasad, president of Apollo Group of Hospitals, Hyderabad. “It has only been because of the relentless and selfless service put in by the health care staff, not just in Apollo but across the country, that we are presently in a better situation. It is easy to criticise hospitals but the community must acknowledge that these institutions have been at the forefront of the fight.” Almost 2-3 per cent of Apollo’s more than one lakh staff across India contracted the disease. “Over a period of time, we started posting only our infected staff in Covid-19 wards because of their developed resistance to the virus,” he says.

Across India, both public and private hospitals were facing a desperate shortage of manpower from March to June. “Even with the government allowing us to recruit across levels, we were unable to get people,” says paediatrician Dr S.R. Lakshmipathy, nodal officer of Covid-19 at K.C. General Hospital in Bengaluru’s Malleswaram area. “They were demotivated, scared and some were aged and had co-morbidities.”

Within three months, the hospital moved from dedicating 20 beds for Covid-19 to being a full-fledged 100-bedded Covid-only facility. Early on, it lost many sick patients, mostly at the time of arrival itself. “Despite lending maximum support to our patients, we were unable to save them,” says Lakshmipathy. Of the nearly 2,000 admissions till date, close to 200 people have died at the facility. The biggest takeaway, says Lakshmipathy, has been the need to boost the morale of the team at all levels. “I remember the nightmarish situation we faced when our attendants refused to turn up. It was a challenge to find people who would do odd jobs, like cleaning, washing and carrying the bodies,” he recalls. “We need leaders who can motivate staff, who are equally vulnerable to the virus as patients.”

The situation was no different in hospitals in Maharashtra, which saw more than 20,000 deaths and nearly six lakh cases in August alone. In Nagpur, which had the highest number of Covid-19 cases in the state after Mumbai and Pune, Alexis hospital faced a “very high attrition rate” during the pandemic as the amount of work had “more than doubled”, says Nilesh Agrawal, administrator in-charge of Covid-19 at the hospital.

Jaslok Hospital in south Mumbai even arranged for buses for its staff after it faced a manpower crunch of close to “50-60 per cent across categories”. Sunil Karanjikar, head, human resources, Jaslok Hospital, suggests having backup accommodation for the staff within three kilometres from the hospital. “This way, they can travel even when transport is not available and we will not lose so many man-hours and essential help in times like these,” he says.

The lack of clear communication guidelines and its percolation down the hierarchy in hospitals has been another problem area, says B.R. Venkateshaiah, medical superintendent of K.C. General Hospital in Bengaluru. “There was much confusion everywhere especially in terms of the protocol to be followed,” he says. “For instance, we had a number of mothers coming to us for delivery and there was a confusion over their Covid-19 status as the test results would mostly come after the delivery had taken place.” Luckily, none of the babies got infected and they were all healthy and breastfed.

Inside the trauma care centre at the AIIMS, Delhi, psychiatrist Dr Srinivas Rajkumar T. says that the management of mental health among Covid-19 patients would have vastly improved “had the government not denied the existence of mental health issues among Covid-19 patients and formulated guidelines early on”. “We observed that mental health issues were also a major cause for hospitalisation of Covid-19 patients and it plays a huge role in recovery as the virus can break even the strong-willed,” he says. “We had so many cases of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the past few months of the pandemic.” According to the guidelines laid down by the health ministry, there are at least three groups affected by mental health during this pandemic. Firstly, patients with confirmed Covid-19 infection may develop mental health problems such as depression (about 30 per cent of the diagnosed patients) and symptoms of PTSD (96 per cent). Secondly, patients with pre-existent psychiatric disorders may experience a recurrence or worsening of symptoms or develop additional psychiatric problems. Thirdly, mental health issues were seen in the general public, too, including anxiety, non-specific psychological distress, depression, stress, insomnia, hallucinations, paranoia and suicidal ideations.

According to Dr Harish Pillai, CEO, Aster-India and Aster DM Healthcare, there were a few loopholes that impacted a hospital’s ability to manage the pandemic. These included rapidly changing regulations, arbitrary price capping on services without proper costing, disruptions in the supply chain owing to the initial phase of strict lockdowns and inconsistent behaviour of health care workers (especially those deployed in non-Covid units) resulting in staff infections. Yet, lessons were learnt here, too. “Nationally it is clear that the health care expenditure as a percentage of GDP needs to be incrementally hiked to an aspirational 5 per cent,” says Pillai. “The enormous resource gap in health care workers needs to be filled and much more investment needs to be made to have better and larger health care facilities in the northern and eastern states. We have now realised the acute shortage of epidemiologists, infectious diseases experts and health care economists.” He also thinks it necessary for hospitals to be designed based on zoning principles that segregate patient traffic. Hospitals should have proper heating, ventilation and air conditioning design, focusing on fresh air flow cycles. The number of beds with piped oxygen supply and those with ventilators also play a crucial role, he says.

The pandemic sure has led hospitals to redefine their strategies and policies for the long term. Right from revising the hospital visitor policy and making it more restrictive, to minimising the presence of bystanders and leveraging technology in the form of web portals and mobile apps to help relatives keep a tab on ICU patients, schedule appointments and make payments, hospitals are taking the challenge of revamping themselves head on.

“The new norm is that every patient who comes in, if planned for admission, will either go for surgery or chemotherapy. But first he has to undergo a Covid-19 test,” says Dr Rajesh Mistry, director, oncology, Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani hospital in Mumbai. “And only if found negative, will he or she be admitted. Plus, the hospital has to take measures to prevent the spread of infection while the patient is in the hospital.”

In the nine months inside the Covid-19 ward at Jaslok Hospital, head nurse Dhanashree Parab, 47, acutely felt the lack of training and knowledge of essential medical concepts among nurses. “We need to keep our nurses well-equipped, too, in terms of knowledge and know-how,” she says. “Sadly, only doctors are given that priority. But given how nurses discharge responsibilities while fighting on the frontlines, trainings should be prioritised for them, too.” Jaslok Hospital underwent a massive disinfection exercise after it was declared a containment zone and more than 60 of its staff tested positive between April and May.

As trials for India’s Covid-19 vaccine begin across state-run hospitals in Mumbai, Bharmal says that we have come a long way. “I know there were hiccups, but that was bound to be there, given that nobody had any clue about how the virus would behave in the first few months of the pandemic,” he says. The hospital has made a number of on-ground policy changes, including revising the discharge policy, which was “most essential because otherwise there was a stagnation and we could not admit more patients,” explains Bharmal. Among infrastructure changes, CCTVs have been installed inside wards, nursing stations and screening OPDs so as to control the activities from a dedicated war room. The entire manpower came together at Nair, including professors and students from the attached medical college. Dr Surbhi Rathi, professor of paediatrics, turned into a skilled administrator when she broke down the entire operation into smaller teams for each aspect. “Formulating of pathways within the hospital so as to keep Covid and non-Covid patients separate in such a large hospital became the foremost task, alongside setting up of screening OPDs,” she says.

Hospitals in India did break their back in tackling Covid-19, but they stood up to the challenge and how.