It was probably India’s first surgical strike. In 1025 CE, Chola emperor Rajendra I changed the course of the subcontinent’s history and became the first Indian to raid an overseas territory. His navy made a stealth attack on the Srivijaya empire—now in Sumatra, Indonesia—and raided its 14 ports.

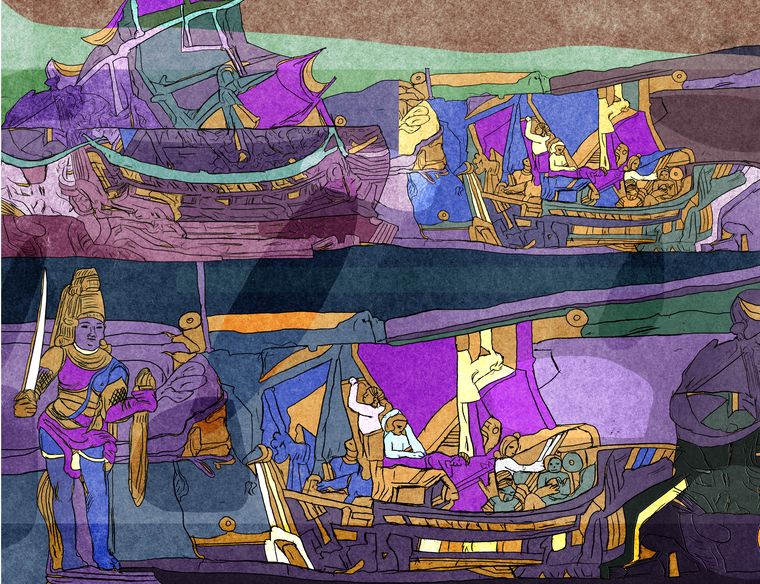

The strike took Srivijaya by surprise. Ships carrying elephants and flamethrowers sailed swiftly into Sumatra, making use of the monsoon winds. They first ransacked the capital city of Palembang and then moved on to other ports. King Sangrama Vijayatunggavarman was imprisoned. According to the Malay version of the story, Rajendra I took Vijayatunggavarman’s daughter Onang Ki as his wife.

Oddly, there is just one inscription by Rajendra I to mark the conquest. The Thanjavur inscription apoetically describes India’s most ambitious naval expedition: “[Rajendra Chola] having despatched many ships in the midst of the rolling sea and having caught Sangrama Vijayatunggavarman, the king of Kadaram [Kedah in Malay peninsula], together with the elephants in his glorious army, [took] the large heap of treasures, which [that king] had rightfully accumulated; [captured] with noise the [arch called] Vidhyadhara-torana at the ‘war-gate’ of his extensive city; Srivijaya [Palembang] with the ‘jewelled wicket-gate’ adorned with great splendour and the ‘gate of large jewels’.”

But this was not the first time the Cholas had taken to the sea to expand their boundaries. Rajendra’s father, Rajaraja Chola, had invaded Sri Lanka and established a seat of power in Anuradhapura. “Later, Rajaraja attacked the Maldives,’’ writes Noboru Karashima in The Concise History of South India. “To profit from trade, he sent envoys to the Chinese court.’’

The Cholas were possibly one of the longest ruling dynasties in the world. The earliest reference to the Cholas can be seen in the major rock edict of Ashoka in 3rd century BCE. It mentions them as friends of the Mauryan empire. The dynasty continued to rule till the 13th century. There are also references to the Cholas in Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, the world’s first guide to navigation and trading. Ptolemy, too, mentions them. The eastern coast of peninsular India got the name Coromandel from the Cholas. It is a corruption of Choramandala or Cholamandala, which means the realm of the Cholas.

The Cholas were great patrons of art, architecture and sculpture, building enormous temple complexes across the eastern coast. Their bronzes made the west sit up and take notice of Indian art. The image of Natraj was created and popularised by them. There had never been an image of a dancing Shiva before and as Charles Allen writes in Coromandel: A Personal History of South India, it was “an image so revolutionary that it could have been made only by powerful royal backing”.

But more than just their contribution to culture, the Cholas made their mark by being the first Indians to plant their flag outside the subcontinent. Apart from their powerful navy, they had an intelligence corps called ottru to monitor foreign vessels, while kallarans—reformed pirates—were deputed informally to keep a watch on rogue elements in the seas. They also had a coastal defence system complete with a coast guard.

The attack on Srivijaya is now being interpreted as a geostrategic manoeuvre. While it is commonly believed that Rajendra I crossed the sea as part of his desire to push the boundaries of his empire further, new research by historian Tansen Sen suggests that the attack was a pre-emptive strike with a commercial motive, aimed at averting a trade war.

In his book Zhu Fan Zhi (A Description of Barbarian Nations, Records of Foreign People) written in the 13th century, Chinese historian Zhao Rukuo says Srivijaya was forcing foreign ships to stop at their ports. Their navy would destroy those ships which refused to do so. Rajendra I’s attack was perhaps an attempt to defend the trade system as the Srivijayan interference was hurting the Cholas.

The 11th century was a period of great geopolitical turbulence. The rise of the Cholas, the Faitimids in Egypt and the Song dynasty in China ensured that the balance of power in the Indian Ocean region was in a state of flux. Trading activity in the Muslim world shifted from the Persian Gulf to the Red Sea, with Egypt becoming more powerful. The Songs were pushing for more trade and the Cholas had added the Maldives to their empire and had vanquished all challengers in the Bay of Bengal. Rajendra wanted to make the most of the situation. Capturing Srivijaya, which controlled the straits of Malacca and the Sunda, would give them a monopoly on trade.

Another reason that prompted Rajendra to launch the strike was an entreaty from the Khmer (Cambodia) king Suryavarman I, who had a running feud with Srivijaya, says maritime historian Sanjeev Sanyal. After the Srivijayan king turned to China for protection, Suryavarman reached out to the Cholas to set the balance right. With China trying to influence trade routes along with Srivijaya, the Cholas knew they had to act. A pre-emptive strike was their best option. And it worked. The audacity of the Cholas shocked countries of Southeast Asia so much that none of them dared to send an envoy to China for three years. The surgical strike was worth the risk.