Shaikh Dawood Hasan turned 65 on December 26 last year.

He is the patriarch of a large, prosperous family in Karachi, but there was no celebration or even a family gathering on his birthday. His house—D-13, Block 4 at Clifton, an affluent seaside neighbourhood in the city—is guarded by plainclothesmen. But the house has been quiet for some time; its residents are away.

Five feet and six inches tall and of medium build, he appears clean-shaven in his passport photograph, quite remote from his grisly persona. Before he came to Pakistan as a fugitive and changed his name in the 1990s, he was better known as Dawood Ibrahim Kaskar. For nearly three decades, Hasan aka Dawood has been ‘eluding’ intelligence and security agencies across the world, despite the United States having declared a $25-million bounty on his head for his role in the 1993 Bombay blasts.

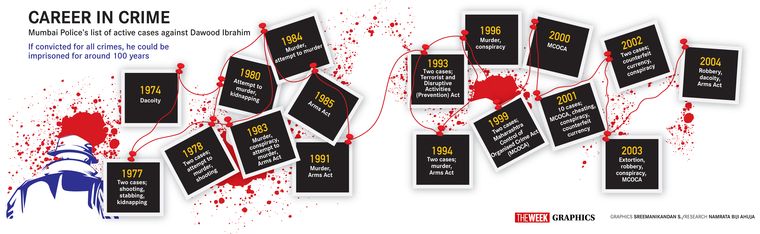

Though Dawood has long been India’s most wanted man, he travels around the globe under aliases without being caught at immigration points. The D Company, which he started in the 1980s, was a smuggling, murder and extortion syndicate. Today, it is a corporate empire with multiple verticals looked after by separate managers. It is spread across Asia, Africa, Europe and even North America, with distinct wings that run guns, plant bombs, print fake currencies, buy and sell real estate, run factories, smuggle drugs and kill people.

Indian agencies have discovered that Dawood is not in the pink of health. He has blood pressure-related problems, and there were rumours that he had contracted Covid-19. Sensing that the times are changing, Dawood is apparently keen to pass on his shady empire to capable hands.

The big question is: who will succeed him?

Dawood would know that the succession (or a division of the empire, if needed) has to happen while he is firmly in charge. For criminal empires like his tend to end up in bullets and blood, much like in the underworld movies he once produced clandestinely. Also, the Pakistani spy agency Inter-Services Intelligence, which has been helping him run his businesses, wants a smooth succession.

But this was not the only reason that Dawood chose to have a low-key birthday in Europe, away from his family. Dossiers with Indian intelligence agencies, which THE WEEK has seen, reveal that Dawood and his family are permanent residents in Pakistan with computerised national identification cards (CNIC) issued by the interior ministry. These are similar to India’s Aadhaar.

The dossiers indicate that he is currently in Europe; Pakistani sources say he is in the UK. But every country denies his presence on its soil. “Pakistan had asked him to leave the country for some time because of pressure from the Financial Action Task Force,” a top Indian government official told THE WEEK. “We know he is somewhere in Europe.”

Last August, Pakistan finally admitted that Dawood had been living on its soil. It released a list of 88 banned terror groups and their leaders who were under severe financial sanctions imposed by it. It included Jamaat-ud-Dawa chief Hafiz Saeed, Jaish-e-Mohammed chief Masood Azhar, and Dawood. The document had Dawood’s address as ‘White House, near Saudi Mosque, Clifton, Karachi’, and listed several properties he owned, including “House number 37, 30th Street, Defence Housing Authority, Karachi” and a “palatial bungalow in the hilly area of Noorabad in Karachi”. Pakistani officials later said these addresses were part of the UN’s sanctions list and that no such person existed in their own records.

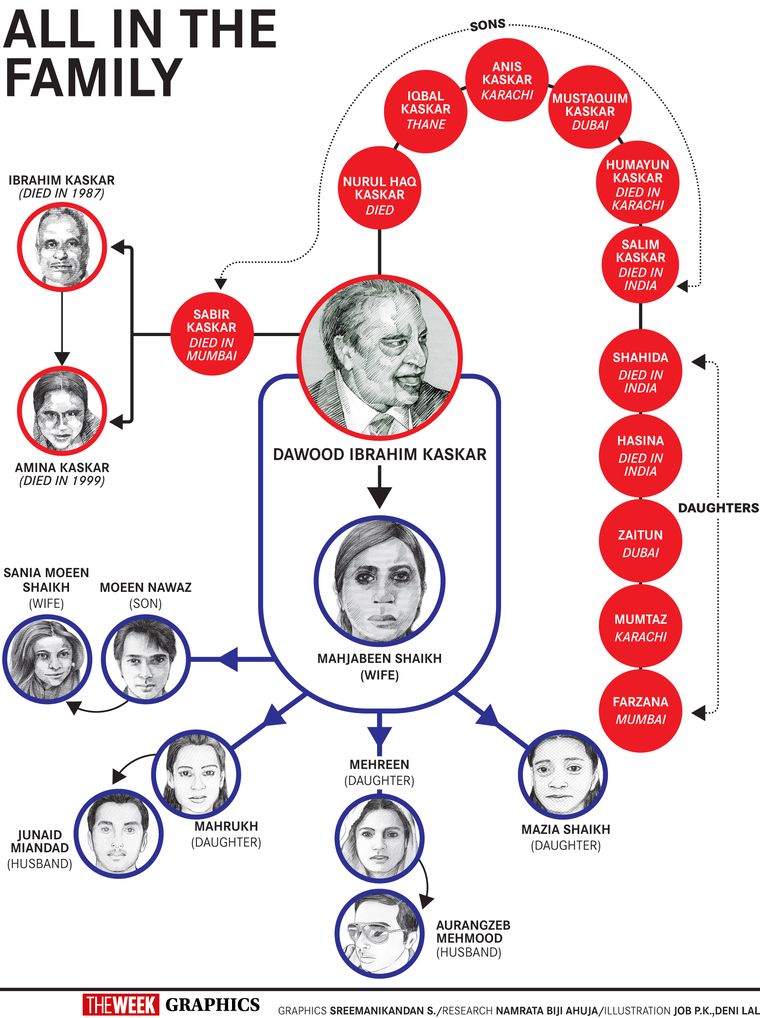

Having become a grandfather, Dawood has reportedly taken a back seat in family and business matters, apparently to make way for a successor. The second generation of the Kaskar family has grown in size, age and experience. Dawood’s immediate family includes his wife, Mahjabeen Shaikh alias Zubeena Zareen, 55; son Moeen Nawaz, 32; and daughters Mahrukh, 34; Mehreen, 33; and Mazia Sheikh, 22. Then there are Moeen’s wife, Sania; Mahrukh’s husband, Junaid Miandad; and Mehreen’s husband, Aurangzeb Mehmood. Mazia, the youngest daughter, is unmarried. All of Dawood’s children have permanent addresses in Karachi, with business interests and properties spread across Islamabad, Dubai and London.

Then there are Dawood’s siblings. Of the original 12—seven brothers and five sisters—only six are alive. One of the brothers, Anis Kaskar, is living in Karachi and another brother, Mustaquim Kaskar, in Dubai. Yet another one, Iqbal Kaskar, has been in Thane jail since his arrest in an extortion case in 2017. Sisters Zaitun, Mumtaz and Farzana are in Dubai, Karachi and Mumbai, respectively.

Though Dawood has been on the run for decades, he continues to maintain links with his relatives in Mumbai (see story on page 40). Mahjabeen, his wife, calls their relatives regularly to keep abreast of developments and exchange greetings on Eid and other festive occasions. She has ensured that her children meet and interact with their cousins regularly—often in Dubai. “It was the dream of Dawood’s mother that the family stays together,” said a distant cousin. “Mahjabeen has carried it forward by teaching her children to mix with the family despite all the constraints.”

Apart from blood relatives, there are Dawood’s two main aides, Chhota Shakeel and Fahim Machmach, who run businesses across the globe. “They are the Indian and international faces of the D Company, which now functions like a corporate entity with several verticals,” said Milind Bharambe, joint commissioner of police (crime) in Mumbai.

So, who will inherit Dawood’s empire? Or, if it is going to be broken up, who will get what?

Indian officers say three front-runners are: Dawood’s son Moeen Nawaz, son-in-law Junaid Miandad and the trusted second-in-command Chhota Shakeel. Dawood would like Moeen to inherit his mantle, but many in the D Company consider him to be “soft”. “Moeen is a hafiz (someone who knows the Quran by heart),” said a relative of Dawood. “He dedicates a lot of time to religious studies.”

Junaid, on the other hand, is known to have a sharp business acumen, and many expect him to succeed Dawood. Dawood’s brothers Anis and Mustaquim are also eyeing the throne. Mustaquim is in charge of the export-import business and runs the drug racket in Dubai. Anis is in charge of the gutka (tobacco) business and paper factories; he oversees the printing and distribution of fake Indian currency notes. In 2015, the US Department of Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control registered a case against Anis and his paper mill in Sindh under the US Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act for printing fake Indian rupee notes.

With five names in the running—Moeen, Junaid, Shakeel, Anis and Mustaquim—the endgame is near. It could be a break-up of the empire or a bloody succession war. Anticipating this, many of Dawood’s lieutenants have started aligning themselves with their preferred candidates, or are trying to gain full control of their branches and drift away.

Moeen has for long been Dawood’s first choice. The ISI also has had its eyes on him after he quit regular studies to become a hafiz. The ISI has always been wary of Dawood’s business acumen, even though it had used it to its advantage. Realising that his business interests would supersede his loyalty to Pakistan, the ISI has been grooming his son into a hardcore Pakistani asset.

Since the early 2000s, Dawood and his close associates have been making investments around the world—some beyond the reach of the ISI. He has been parking funds in the west, particularly in real estate in the UK, where his daughter-in-law lives. Moeen regularly visits his wife in London, where he also has business interests. But since he is not known to be as sharp as his father, rivals can rise up and claim the throne.

Moeen’s chief competitor is Junaid, 38, who is smart, well educated, shrewd and ruthless. Junaid is the son of former cricketer Javed Miandad, and he maintains that his family only has personal ties with Dawood. But there are rumours that his marriage is under stress, because of which his relationship with Moeen has reportedly soured. Dawood’s family, however, has denied such rumours; sources say Junaid is in Dawood’s good books.

But many D Company leaders, including Dawood’s brothers, view Junaid as an outsider. Also, Javed Miandad knows that India wants to break the backbone of the D Company. So the Miandad family may not like the possibility of Junaid succeeding Dawood—at least until the sticking points are ironed out.

Though they are ageing, Anis and Mustaquim view themselves as rightful claimants to the throne. They have been with Dawood through thick and thin, and feel that the family business should not be divided among outsiders. Dawood, however, reportedly has more confidence in Chhota Shakeel than his brothers, and that makes Indian intelligence agencies uneasy. For Shakeel, who stays in a mansion close to Dawood’s home in Karachi, is hand in glove with the ISI and focuses on India-related operations.

Most people in the D Company expect Shakeel to take over the reins. He has been Dawood’s trusted general and conscience keeper for decades, and knows the nitty-gritty of running the empire. Dawood also knows that the ISI would like Shakeel to succeed him. With the US withdrawal from Afghanistan imminent, the ISI’s arms in the country are likely to be activated again. Having the trusted Shakeel at the helm of the D Company would serve Pakistan’s geopolitical interests.

Much will depend on whom the lieutenants that run the empire’s various verticals will back. They include Javed Dawood Patel, alias Javed Chikna, an accused in the Bombay blasts case who lives in Karachi and runs drug operations in Mozambique and South Africa; Shafi Memon, who is based in Mauritius; Sameer Hanif, who runs several US-based operations and is reportedly close to Shakeel; Hazi Samat, a Pakistani national who heads businesses in Tanzania; and Madat Saburli Chatur, a Kenyan national of Indian origin who is in charge of operations in Kenya.

The D Company has invested in real estate in Dubai and London. The Dubai investments are looked after by Yasir Iqbal, Raees Farooqui, Anil Kothari and Faisal Jafrani. The hawala operations are controlled by Anis Lamboo, who is reportedly in the UAE. The betting business and other investments in the US are looked after by Javed Chhotani, a Pakistani national who was the link between Dawood and Indian bookies when the spot-fixing scandal in the Indian Premier League broke in 2013.

Another stakeholder who may have a say in the D Company’s future is Altaf Khanani, who runs a money laundering organisation called Khanani MLO from Pakistan. In November 2015, the US designated Khanani MLO as a transnational criminal organisation that moved funds for the Taliban and had links to terror groups such as Lashkar-e-Taiba, Al Qaeda and Jaish-e-Mohammed. It also launders money for Chinese, Colombian and Mexican cartels, and has been accused of facilitating illicit money transfers between entities in Pakistan, the UAE, the US, the UK, Canada and Australia. Details of Khanani MLO’s operations were revealed after Dawood’s lieutenant Jabir Motiwala was arrested in London in August 2018, for importing prohibited drugs to the US.

Similar arrests in the past few years have thrown further light on the D Company. The biggest of them was of Sohael Shaikh, son of Dawood’s deceased brother Noora Kaskar, in Barcelona in June 2014. The US Drug Enforcement Agency and the Spanish police arrested Shaikh for allegedly importing, exporting and distributing narcotics; providing resources to terrorists; and conspiring to transport missile systems allegedly to protect drug-trafficking syndicates. Shaikh was also accused of having links to Russian gangsters and the Colombian guerrilla group Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC). He was extradited to the US and was sentenced by a federal court in 2018. India, too, is seeking to interrogate him.

The US has designated Dawood as a “global terrorist” who runs guns for Al Qaeda and the Taliban; his aides Shakeel and Ibrahim “Tiger” Memon have been designated as “foreign narcotics kingpins”. But with the US keen to exit Afghanistan, a resurgent Taliban is expected to lift the D Company’s prospects.

Security agencies in India worry that the situation would embolden Dawood to strike in India again. The police in Delhi, Mumbai, Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh have received inputs that the D Company is re-activating its contacts in India. “We cannot put a figure to the number of people linked to Dawood or the D Company in the country,” said a Delhi Police officer. “But the support base is very much there. They also use assets of LeT and other Pakistan-supported terror outfits when required.”

The problem is that the D Company works with such finesse that it often leaves few footprints. On February 7 this year, the CBI closed a case of attempted murder that had been filed against Chhota Rajan. A former Dawood associate, Rajan had been on the run for more than 20 years; in 2015, he was extradited from Bali to India. He had fallen out with Dawood, and had even tried to kill him in 1998. Rajan, whose life is under threat, is now lodged in Tihar Jail.

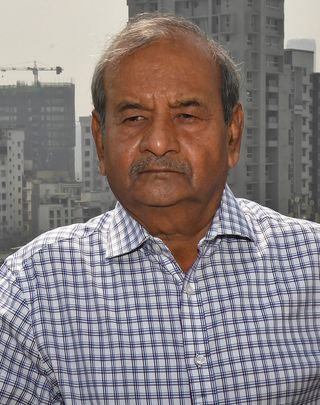

It is not just Dawood’s foes in jail who fear him; the officers who have investigated his wrongdoings also live with haunting memories. Suresh Walishetty, who was investigating officer in the 1993 Bombay blasts case, recalled how he walked a tightrope while establishing contact with the underworld in the heyday of the D Company’s smuggling operations.

“One day, when I was investigating cases against the [Bombay] underworld, my seniors asked me to establish contact with [the gangsters],” he said. “I knew that the Mumbai Police would not be able to save me if I got caught in the crossfire between them and various police agencies. I did not proceed until I got an assurance from the commissioner of police.”

Walishetty said he gradually established contact with the gangsters. “One day, news broke of the murder of a prominent figure and the Bangalore Police came to Mumbai. They found my numbers and addresses during investigation and started looking for me. My cover would have been blown.”

As luck would have it, since Walishetty knew Kannada, his seniors asked him to help the Bangalore Police in the case. “I was saved from further investigation only because my seniors were aware of my role,” he said.

The D Company, said Walishetty, had been using sea routes to smuggle in gold and silver. But now, the nature of Dawood’s businesses has changed. With the help of ISI officers, Dawood, Shakeel and Javed Chikna have been pumping in fake currency notes to India through Nepal and Bangladesh.

The D Company also controls a significant share of the global illicit drug market. Drugs from the Makran coast of Pakistan are split into two pathways—to the Maldives and Sri Lanka to the southeast, and to Mozambique, Kenya and Tanzania to the southwest. From the East African coast, the drugs are transported to South Africa and the west. The D Company has also established strongholds in many countries—especially in South Africa, where the presence of Pakistani immigrants has made operations smooth.

Politicians in India have long faced threats from the D Company, especially from Shakeel. In November 2015, shooters allegedly sent by Shakeel’s aide Abid Dawood Patel tried to kill two local leaders of the BJP in Gujarat. Shakeel was also allegedly involved in the bid to murder Pakistani-Canadian writer Tarek Fatah in June 2017. Another close associate of Shakeel—Farooq Gani alias Hazrat—helped an Indian national, Faisal Hasamali Mirza, to travel to Karachi via Dubai without requisite documentation. Mirza, who allegedly underwent training in making explosives, was later arrested in India.

A big question: would Dawood ever be brought back to India to stand trial?

The BJP had claimed in 2014 that it would nab Dawood from Pakistan if it was voted to power. But Pakistan continued to deny that Dawood was on its soil. “I wonder what stops India from seeking justice from the International Court of Justice to [obtain access to] Dawood Ibrahim, like it had done in the case of former Indian Navy officer Kulbhushan Jadhav,” said Bashir Wali, former director of Pakistan’s Intelligence Bureau.

Walishetty, however, believes that it would serve little purpose to bring in Dawood now. Proving cases against him, too, may be an uphill task, with “all the police officers who probed the cases having retired”. “I don’t think Dawood holds any significance today,” said Walishetty. “He will be a burden on the system if he is brought back. Moreover, no political party has the will to bring him back.”

A.B. Pote, former deputy commissioner of police (detection) in Mumbai, said Dawood still had a wide network of lawyers and prominent people capable of getting him acquittals. “[Dawood and his associates] are masters of the game. They know how to exploit lacunae in the law,” he said.

Senior intelligence officers said it was better to track and break Dawood’s empire than hunt him down. He may die in a few years, said an officer, but the empire could flourish under a successor or group of successors. “We need to cooperate with friendly powers to break its back,” said a senior Intelligence Bureau officer. “That is the only way to secure India.”