Smelling jasmine at India’s Tahrir Square—Jantar Mantar. I am going there. Are you?” This was one of the many social media posts that called upon people to join the agitation launched at Delhi’s protest hotspot a decade ago, to demand the enactment of the Jan Lokpal Bill.

Comparisons with the “Arab Spring” were apt, for Jantar Mantar saw a rare flood of people, especially the youth, bringing to mind the series of anti-government protests that had rocked the Middle East in the preceding months.

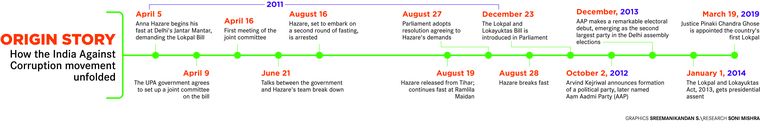

It became more appropriate as spring had arrived in India’s capital when veteran activist Anna Hazare took the stage at Jantar Mantar, demanding that a law be passed without delay for setting up an anti-corruption ombudsman. It was on April 5, 2011, that Hazare, who was till then not so well-known in Delhi, started his hunger strike. The timing was perfect as the Congress-led ruling dispensation at the Centre was struggling to free itself of numerous allegations of scams. In response to the pressure built up on his government by the civil society, the then prime minister Manmohan Singh had added to the season-inspired description of the situation to say, quoting English poet P.B. Shelley: “If winter comes, can spring be far behind?”

Singh’s response was misplaced since the all-too-brief spring is a season of transition, followed in the northern plains by a punishing summer. And, Anna Andolan, as the IAC movement came to be popularly known as, heralded a summer of discontent.

The Gandhian from Ralegan-Siddhi, a hamlet near Pune, was seen as a simple, elderly, straight-talking commoner taking on the high and mighty. The response that the movement received from people surprised not just the government but also the organisers of the campaign; Hazare’s hunger strike had a ripple effect across the nation. It stirred the otherwise politically-nonchalant urban middle class and brought the youth to the streets.

A decade later, Jantar Mantar saw another agitation challenging the Central government. There was a strong throwback to the summer of 2011, but there were many dissimilarities, too; and the elements of the more recent protest threw light on the far-reaching changes that have taken place in the country’s political atmosphere over the last decade.

Hazare, the face of Anna Andolan, was absent from the scene. Following the disintegration of the IAC core group, Hazare has receded into the background, holding dharnas (strikes) and anshans (fasting) on various issues, but with far less public involvement than the IAC campaign.

Occupying centre stage at the recent Jantar Mantar event was Arvind Kejriwal—the brain behind the IAC movement. Kejriwal, now chief minister of Delhi, was the lead speaker at the agitation, a far cry from 2011 when the Indian Revenue Service officer-turned-activist preferred to work behind the scenes and had to be dragged onto the stage.

Kejriwal’s Aam Aadmi Party, the political outfit he founded along with a section of the IAC leadership, is in power in Delhi, and the recent agitation was meant to protest the Union government’s move to bring in a legislation that gives more powers to the lieutenant governor of Delhi, thereby curtailing the authority of the state government.

If the AAP can be described as the most successful political startup of the last decade and Kejriwal the fastest-rising leader, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his party were arguably the biggest beneficiaries of the IAC movement. An outcome of the Anna Andolan was that Modi got an opportunity to build an election campaign on the promise of fighting corruption in the Lok Sabha elections in 2014.

Modi has since consolidated his position, moving on from the anti-corruption plank to issues closer home to the hindutva brigade, while the Congress has hurtled from one electoral debacle to another, unable to recover from the devastating loss of 2014.

Also read

- BJP government, too, did not want the lokpal law

- IAC’s goal was to display the power of people

- RSS and BJP had a role in the campaign

- The IAC campaign has done more harm than good

- The movement failed to provide a credible alternative

- We are establishing ourselves at the national level

- The IAC movement was hijacked by Kejriwal

Also, even while some faces at the recent agitation by the AAP had also been seen during the IAC movement, several others were missing; they either chose to go back to their original vocation or found space elsewhere in the political sphere. During the IAC heyday, a motley group of people espousing diverse ideological streams led the campaign. If Hazare, with his Gandhian methods, was the face of the campaign, legal stalwarts like Justice N. Santosh Hegde and Shanti Bhushan shared the stage with bureaucrat-turned-activists like Kejriwal and Kiran Bedi. Added to the mix were people from diverse fields—activist-lawyer Prashant Bhushan, poet Kumar Vishwas, former journalist Manish Sisodia, and spiritual leaders, Baba Ramdev and Sri Sri Ravi Shankar. The campaign also attracted several social activists such as Yogendra Yadav, Mayank Gandhi, Sanjay Singh and Gopal Rai.

The group has since disbanded, and some of the former IAC members, prominent among them being Yogendra Yadav and Prashant Bhushan, carried on for a while in the AAP before they parted ways with the party.

Kejriwal and the AAP have been attacked by ex-IAC members for losing track of the principles on which the campaign, and later the party, were formed. The AAP, critics say, has little to distinguish it from the traditional political outfits, and Kejriwal is called out for making ideological compromises for the sake of electoral success. The party, however, looks to expand its national footprint, riding on the success of its model of governance in Delhi.

Coming back to the main demand of the IAC campaign, Lokpal has become a reality. While the law was passed in December 2013, the ombudsman was finally appointed in March 2019. However, activists slam the Lokpal law as a weak legislation and are disappointed with the performance of the anti-corruption watchdog so far.

The legacy of the IAC campaign is a mixed bag. While it has had a profound impact on the country’s politics, the anti-corruption sentiment has died down. The whiff of jasmine has faded away.

Perhaps, some other time, and on some other issue, Jantar Mantar will come alive once again.

In the meantime, prominent members of the IAC movement share with THE WEEK their memories of those heady days, their assessment of the campaign’s outcome and what lies ahead.