In 2006, Assam chief minister Tarun Gogoi ridiculed Badruddin Ajmal, asking who he was. Ajmal had floated a new party the previous year to represent the interests of Muslims in the state. Gogoi did not want to reinforce the Congress' pro-Muslim image, so he kept ignoring the perfume baron. The grand old party was presented as the sole representative of the ethnic Assamese identity.

However, in early 2020, as the agitation against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) raged across the state, 84-year-old Gogoi finally shed his resistance and batted for an alliance between Ajmal's All India United Democratic Front (AIUDF) and the Congress to defeat the BJP.

The Congress's rainbow alliance for the assembly elections—including parties like the AIUDF, the left and the Bodoland People’s Front (BPF)—meant it was certain to increase its vote share and seats. But when the votes were counted, the alliance had almost the same vote share as the NDA, despite the latter facing the wrath of the people over the controversial citizenship law. The BJP managed better chemistry with the electorate, trumping the grand alliance's arithmetic.

The BJP created its narrative against the Congress-led alliance, terming it detrimental to Assam's interests, thus managing to turn the tide from anti-government sentiment to pro-incumbency. The polarisation was fuelled by fears of Bangladeshi Muslims capturing political power through the Congress-AIUDF alliance.

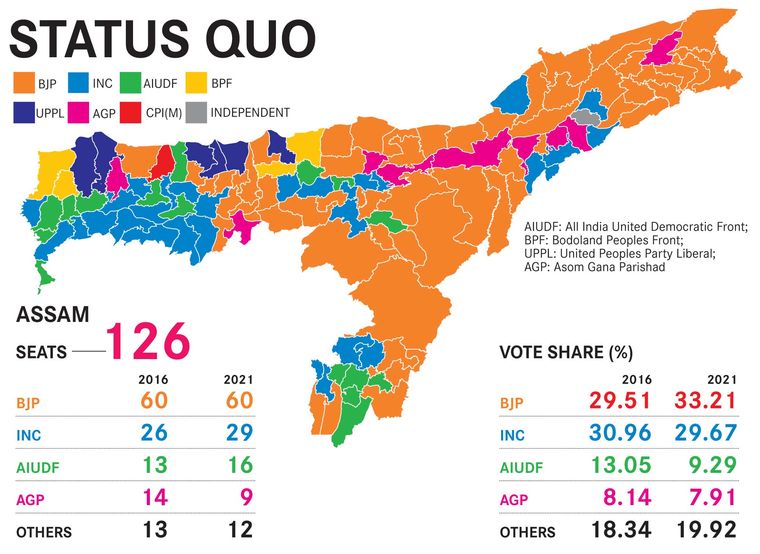

The newly constituted Assam assembly now has 31 Muslim MLAs—up from 29 in 2016—the highest in four decades. Of these, 16 are from the Congress and 15 from the AIUDF. While the Muslim vote may have consolidated behind the alliance, the counter polarisation meant the BJP cornered most of the seats in Upper and north Assam. The party returned to power by winning 60 seats and allying with Asom Gana Parishad (nine seats) and the United People's Party Liberal (six) in the 126-member house.

That Ajmal was painted as one representing the interests of illegal Bangladeshi Muslims worked in the BJP’s favour. “Thirty per cent of the population (of Muslims) creating trouble for the 65 per cent population” was the theme played by the BJP, especially by Himanta Biswa Sarma, to channelise anti-CAA anger towards the threat posed by the AIUDF.

Unlike in other states, where Muslims mostly opposed the CAA, in Assam, the opposition to the law was based on linguistic reasons as indigenous people did not even want Bengali-speaking Hindus to be regularised.

The polarisation in the state has thrown up an interesting trend. The Assamese sub-nationalism was represented by parties like the Asom Gana Parishad, which was born out of the 1980s Assam agitation as several All Assam Students Union (AASU) leaders formed it. During the anti-CAA protests, the AGP was thought to have left the cause as it was a BJP partner. Two new outfits were born out of the current agitation—the Assam Jatiya Parishad (AJP) and the Raijor Dal, again supported by the AASU.

The results show that people have reposed faith in the BJP—a national party—to stop illegal migration, over these parties representing Assamese identity. The AJP, which contested in 80 seats, failed to even win one, while Raijor Dal's Akhil Gogoi, currently in jail, was the sole winner.

The Congress, too, blamed the two new regional outfits for its loss. “There has been a unique development in the current elections. There is a big question mark on the role of the AJP and Raijor Dal,” said Jitendra Singh, Congress general secretary in charge of Assam. “These parties were formed out of the anti-CAA agitation. They have helped the BJP win several seats in the Upper Assam region. They in fact helped the same party they were meant to oppose.”

The feeling within the AIUDF is that aligning with the Congress did not help. “As it is, we used to win up to 18 seats when fighting the Congress. Had we contested alone, our count could have been between 22 to 26,” said Aminul Islam, AIUDF general secretary. “We contested 19 seats and won 16. The Congress contested 95 but won 29, of which the majority are Muslims. It should have been aggressive in reaching out to other communities. Its campaign was missing in Assam, as they only focused on minority areas.”

“The BJP turned the campaign into an emotional issue, and targeted Badruddin Ajmal only,” said Islam. “Like the Raijor Dal and AJP, we were also opposed to CAA, but instead of them making BJP their target, the two parties focused on us. This confused the voters in Upper and North Assam, and led to division in secular votes.”

The BJP has been a gainer in its nationalistic agenda to save Assam. Its ideological parent, the RSS, has been working in the state to win over local tribes and people so that the demographic profile of the state does not change further, and the political power remains with the ethnic majority.

“The Congress and the AIUDF were focused on one agenda and messaging,” said Pawan Sharma, BJP co-in-charge of Assam. “The people saw that. They heard their speeches. The people felt if our borders are not safe then what is left? If the culture is not safe or is insulted, if people don't get respect… they witnessed it.”

As Covid-19 doused the anti-CAA protests, the BJP focused on bringing the state’s ethnic tribal minorities into the fold, and even promised scheduled tribe status to six communities, which helped it win over the indigenous tribes in Upper Assam.

“The people of Assam have brought back the BJP and NDA for the enormous developmental work done in the past five years,” said Jay Panda, BJP state in-charge. “The focused attention given by Prime Minister Modi to the state and the northeast is more than any of his predecessors.”

With the BJP left to decide who will be the chief minister, both candidates, Sonowal and Sarma present strong cases for themselves. The BJP needs them both. By retaining its first government in the northeast, the saffron party has kept its gateway to the region open. Both men have important roles to play—to keep the state government stable and to keep an eye on the region.