Last year, when the pandemic began wreaking havoc in India, people in Kerala formed a new habit. Every day at 6pm, they would gather in front of the television to listen to a man who was not known to be media-friendly. Like a disciplinarian headmaster who rarely smiled, he would give updates regarding the pandemic and the measures the state government was adopting to mitigate the crisis. He made sure that nobody in the state went hungry, asked men to support women in household chores, and even advised people to take care of stray dogs during the lockdown. He would wind up the briefing at 7pm, but in that one hour he gave Malayalis something they deeply valued during the difficult times—a sense of security.

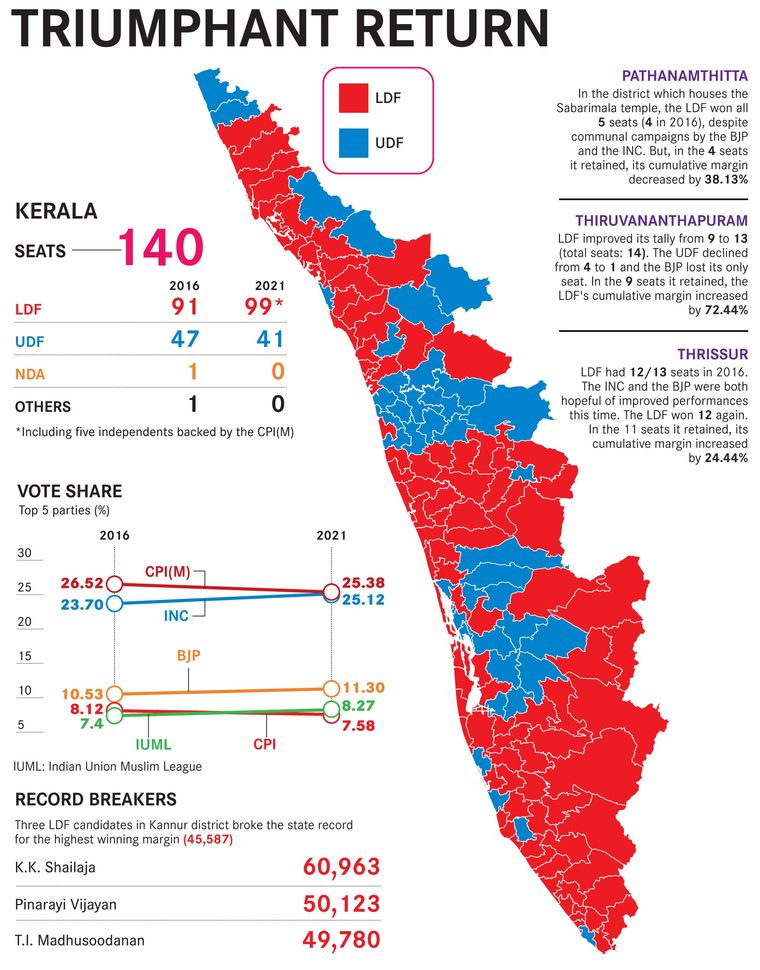

No wonder that Kerala has re-elected him, Pinarayi Vijayan, as its chief minister for the next five years, too. Under Vijayan, the CPI(M)-led Left Democratic Front (LDF) swept the assembly polls, winning 99 of 140 seats. The Congress-led United Democratic Front bagged 41 seats, while the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance drew a blank, losing even the lone assembly seat it had won in 2016. Vijayan has become the first Kerala chief minister to complete his term and win the following election.

“This election belongs to Vijayan,” said writer Paul Zacharia. “The opposition stood no chance, because people trusted him. He delivered on what he had promised and people could not imagine anybody else in that chair. Malayalis were watching what was happening in other states, and they knew they were in safe hands.”

According to actor-writer Renji Panicker, the way the government handled the Covid crisis played a crucial role. “The caring hands of the government reached every home, through food subsidies and initiatives of civic bodies and the health department,” he said. “The common man could feel the presence of the government in their lives. They felt safe; they wanted that feeling to continue.”

The fight was hardly easy for Vijayan. National leaders—Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Union Home Minister Amit Shah and Congress leaders Rahul and Priyanka Gandhi—were criss-crossing the state, attacking the state government and personally targeting Vijayan. Helping their cause were Central agencies like the Enforcement Directorate, the National Investigation Agency and the customs department, which have been after the chief minister’s office ever since it was alleged that Vijayan’s principal secretary was involved in the gold smuggling scandal that broke in July last year.

But Vijayan remained unfazed. What gave him confidence was the way the LDF had swept the local body polls in December last year, when the smuggling controversy was at its peak. “We trusted the people and the people trusted us,” said Vijayan about the poll results.

Apart from social security measures, the LDF government also highlighted its track record of good governance in the run-up to the assembly polls. The public health care and education systems in the state got a leg up like never before in the past five years. The government also implemented an array of infrastructure projects. “Malayalis had many reasons to give the LDF a second term,” said J. Prabhash, former head of the political science department at Kerala University.

It may be Vijayan’s confidence that gave the CPI(M) the courage to field new faces in place of its 33 incumbent MLAs, including ministers Thomas Isaac and G. Sudhakaran. This was seen as a huge folly, especially when the Congress fielded candidates who were popular. But, as the results showed, Vijayan’s confidence was not misplaced.

“He is not your typical conservative communist chief minister; his outlook is quite in tune with the times,” said D. Dhanuraj, head of the Centre for Public Policy Research in Kochi. “This has attracted young voters cutting across caste and religion. That Vijayan could establish himself as a leader who did well in the hour of crisis, while the opposition had no such figures, worked wonders for the LDF.”

Some clever social engineering, too, worked in the CPI(M)’s favour. The most important among them was the induction of the Kerala Congress (M)—a predominantly Catholic party known for its anti-communist rhetoric—into the LDF. The decision had upset the puritans in the LDF and a part of the cadre. But it is evident from the results that the KC(M)’s entry benefited the LDF in central Kerala.

Vijayan also wooed back the Muslim community, which had voted for the UDF in 2019 Lok Sabha elections. The Indian Union Muslim League (IUML), a constituent of the UDF, got fewer votes this time even in its bastions in Malappuram district. It won only 15 seats, three fewer than in 2016. Even a section of the Nair community, which traditionally supports the Congress, voted for the LDF.

Under Vijayan, the LDF also set the poll discourse. “The CPI(M) had a story to tell and it had a master narrator in Vijayan,” said Prabhash. “The Congress did not have a story; nor did it have a good narrator.”

Said psephologist Sajjad Ibrahim: “The LDF, especially the chief minister, attracted almost all sections, cutting across age, class, caste and gender barriers. That is the reason behind this sweep.”

The Congress’s only solace is that the BJP did not get any seats. The poor show, despite a high-voltage campaign by the Gandhis, shows that the Congress is in crisis. “The results have exposed everything that was wrong with the state unit,” said Nizam Syed, a political observer. “But it has also exposed the central leadership, especially the Gandhis.”

The factions in the Congress’s state unit had buried their differences to present a united front. The central leadership was also directly involved in selecting the candidates. “But all that was of no use, as we did not have a party structure on the ground,” said a candidate who was defeated. “It was wrong of us to believe that all the photo-ops that Rahul and Priyanka Gandhi had created would be converted to votes.”

The Congress’s decision to bank on the controversy regarding women’s entry to Sabarimala also backfired. “The Sabarimala issue helped the Congress in 2019 elections,” said Prabhash. “But when it decided to peg its campaign on the same subject, it proved that it had nothing new to tell the voters.”

The Congress organisation had also become lethargic. “It failed to realise that the anti-communist sentiment that is the backbone of UDF politics is no longer there,” said Zacharia. “The new generation does not carry the remains of the liberation struggle [in the late 1950s] that had divided Kerala society into communist and anti-communist blocs.”

The biggest loser is undoubtedly the BJP, whose vote share plummeted to 11.3 per cent. In the local body polls, it had got more than 20 per cent votes in 35 assembly constituencies. There are allegations that the party sold votes to both the UDF and the LDF, but the leadership denies it. “The minority communities, especially Muslims, consolidated against us in all constituencies where we had a chance,” said state BJP president K. Surendran.

Whatever be the truth, the road ahead seems bumpy for the BJP. “If we are to grow, we would have to either capture Hindu votes from the CPI(M) or win over a section of minority communities,” said a senior RSS functionary. “This would have been possible had we won at least two seats. But with this bad a result, we will have to wait longer.”

Malayalis, meanwhile, have resumed their habit—of waiting for Vijayan’s daily briefing at 6pm.