It was May 2015—early summer in Beijing—when Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his host, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang, attended a tai chi and yoga show at the Temple of Heaven. The tai chi symbol, known to most Indians as Doordarshan’s yin-yang logo, is seen as the epitome of balanced energy. As Li and Modi stepped into the square in front of the temple’s Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests, 400 tai chi and yoga experts from China and India made perfect poses, depicting a balance of strength.

Fast forward to May 2020. The summer breeze turned into a storm and the yin-yang balance got upset when Chinese troops, squatting in the Galwan valley in Ladakh, pounced on a platoon of unarmed soldiers of India’s Bihar Regiment, and beat 20 of them to death with nailed rods, pikes and poles.

Though a minor skirmish for two armies that are among the world’s largest, the incident upset the equilibrium which had been maintained for decades and reinforced with the border agreements of 1993 and 1996. It was restored soon—so to speak—when, on Beijing’s own admission, another battalion of the Indian Army pounced on the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) troopers and killed battalion commander Chen Hongjun and troopers Xiao Siyuan, Wang Zhuoran and Chen Xiangrong. Later, the Chinese Communist Party’s (CPC) Central Military Commission (CMC), headed by President Xi Jinping, honoured them. According to some sources, 45 soldiers were killed.

With blood drawn for the blood that was spilled, it may look like a draw on the high Himalayas for now. However, this balance has been perched delicately for a year now, after several rounds of field commanders’ conferences and even an agreement to retract a few of the combative steps from the Pangong lakeside. They will stay there “in immediate depth” (150km-200km), as Army chief General M.M. Naravane said on May 28, from where they can move forward at short notice.

The PLA has built new troop shelters at Rudok, Kangxiwar, Gyantse and Golmud. “Our troops are also in a high state of readiness and alert,” he said. Rotated troops who have served a few months on the mountains are not being sent down to peace stations, but are asked to stay as a backstop to the forward areas. Both sides are now estimated to have 50,000 to 60,000 troops each in these “immediate depth” positions, even after the February disengagement in Pangong Tso.

Battlefield blood is nothing new for the Indian Army. It has been bleeding in combat every day for the past three decades in counter-insurgency operations in the Kashmir valley, and had also fought a limited conventional war in Kargil, complete with the use of airpower, two decades ago. In 2019, Indian fighter planes flew into hostile airspace and dropped precision bombs on enemy targets, killing more than a hundred dreaded terrorists and terror-cadets, and even engaged in an aerial dogfight downing an F-16. In short, the Indian forces have often been in combat operations, and are always combat ready.

But the PLA’s case is different. The Galwan incident was perhaps the first taste of combat—though without firearms—that it had with an actual enemy after getting a bloody nose in Vietnam in 1979. More than a generation of PLA officers and men had enrolled, served, been decorated and retired since then, without having seen combat. Despite its huge size and the dazzling electronic and cyber gadgetry, all the combat wisdom that the PLA today has is simply drawn from Sun Tzu and his interpreters, and the sand-model exercises.

“The PLA has been facing a challenge of absence of combat experience and a lack of realistic training. It has been widely accepted even within the Chinese establishment,” said Lieutenant General (retd) D.S. Hooda, former northern Army commander. “These weaknesses can only be overcome with doctrinal and training refinements.”

The combat inexperience has been noted by several of China’s own military thinkers. Some of them have openly warned that the PLA may not be able to win a real war against a major power. The thought is particularly distressing for the political and military leadership who have set definite goals for attaining parity with the United States, not only economically, but also strategically and militarily.

Though the Chinese goal of matching the US has been declared earlier, it was only after Xi’s rise that the target of 2027—to mark the centenary of the PLA—was set. The progress on this was reviewed at the CPC’s plenary last November, where it was reiterated that China’s “national defence capabilities and economic capabilities should be strengthened at the same time and reach the centennial goal of building a modern military by 2027.” The review is extremely crucial for Xi and also for the CPC, which celebrates its centenary in July. “Get combat ready,’’ Xi told the uniformed men of the PLA and the People’s Armed Police, as he signed the first order of the CMC last year. “Be ready to act at any second.”

Analysts in India have come to believe that the PLA’s deployment in eastern Ladakh was, among other things, an attempt at validating certain doctrines that should enable the PLA to mobilise and deploy forces in the manner the US and India can. Indeed, the Ladakh standoff has not yet offered any actual combat, but both sides have been using it for testing and validating several of their doctrines of deployment, mobilisation, logistics management, involvement of air power, use of cyberspace and battlefield management.

For India, it has been part of an on-and-off validation process depending on the frequently changing strategic picture and on the money that it can afford, while for China, it has been part of a long-term strategic vision, with definite goals prepared by the CPC and Xi. China has not revealed its assessment of the validation exercise, but China watchers in India’s strategic establishment believe that there is a sense of disappointment in Beijing. Several of the goals apparently have not been met.

As head of the CMC, Xi has been forcing a series of reforms on the 9.15 lakh-strong PLA. If being at par with or surpassing the US is China’s long-term strategic goal, at the tactical level, the goal is to be the overwhelming power in Asia where India has been the major roadblock.

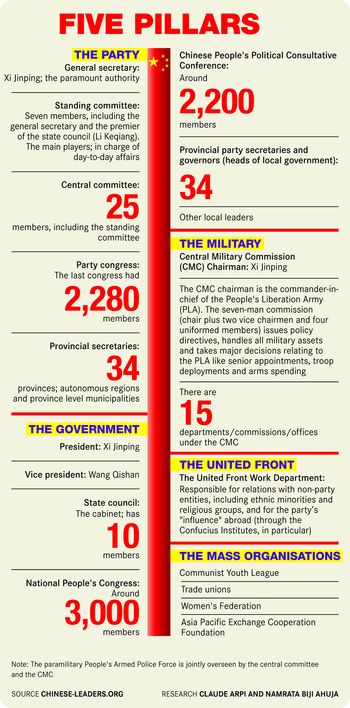

One of the largest exercises was to restructure China’s seven military regions into five joint theatre commands, and to reorganise the four general departments into 15 departments and offices. A separate army headquarters has been established, and the Second Artillery Corps was upgraded to a full service by establishing the PLA Rocket Force. Under the new command system, the entire Indian border is looked after by the western command.

Indian experts believe that most of the reforms in the new western theatre have been designed to acquire a capability to overwhelm the Indian Army on the Himalayas. Since its formation, the western command has conducted two training exercises—in 2019 and 2020. On the eve of every such annual training exercise, a training mobilisation order (TMO), which is a set of instructions for the conduct and goals to be achieved in the exercise, is issued. The TMO for last year’s deployment in Tibet differed from the TMOs of the previous years—it asked the troops to move further forward than in the previous years to positions in Korla, Yecheng, Xaidulla, Kangxiwar, Yangbajain and Shiquanhe for exercises.

The eight-point TMO of January 2019, accessed by THE WEEK, had asked the PLA to adhere to certain operational and capability-level goals given by Xi. It called for conducting military training competitions, highlighting command and joint training, preparing the tactical leadership to take lead in establishing authority, increasing the training on the new technologies that had been acquired, and so on. It also asked the western command to focus on “strengthening realistic confrontation training and preparation to win in an emergency war situation.”

THE WEEK has learnt that in 2020, too, the Xinjiang Military Division, which is under the western command, sent its three formations—4 Motorised Infantry Division, 6 Mechanised Infantry Division and 11 Motorised Division—for these exercises. These movements were deliberately done with open signal communication, so as to be captured by Indian signal units. “Apparently, the idea was to draw out the Indian troops, too, to forward positions, and see how India would counter a move by the PLA,” said an Indian officer who had served in Ladakh. “The unusual thing about the movement in 2020 was the distance they closed into the border. All these training areas are located in such a way that they could serve as launch pads for actual offensive operations against us,” he said. According to a recent statement by General Naravane, the training areas are at a depth of 1,000km to 1,500km from the Line of Actual Control (LAC).

Thus, by late February and early March last year, the PLA had stationed a huge number of troops in the rear areas between Kangxiwar in the north to Rudok in the south, overlooking the contentious areas of Chip Chap, Galwan, Hot Springs, Dambu Guru, Pangong Tso and Spanggur Tso. By June 25, the build-up in the Finger areas had touched about 4,200 soldiers (about four infantry battalions) and another 4,600 behind the Spanggur Tso gap.

Also read

- These men ensure PLA is unlikely to quickly forget the Indian warriors in Galwan

- We are in a new cold war, says former US general Robert S. Spalding

- Indian military needs new doctrinal thinking, writes retired Lt Gen D.S. Hooda

- India needs a dedicated mountain strike corps to tackle China

- Unified theatre command: Why Army and Navy support it, while Air Force is hesitant

- China's defence upgrades are organic, writes Xie Chao from Tsinghua University

While the Indian military leadership was focused on the tactical front, and trying to mirror-deploy forces, the PLA was testing its mass mobilisation doctrines all over China, based on a table-top exercise conducted between January 2 and 12, which indicated the kind of support that a tactical operation against India would require from other commands.

Indian intelligence agencies gather that the exercises and the deployment against Ladakh have, while validating mobilisation doctrines, also exposed several weaknesses of the PLA vis-a-vis the Indian Army and its deployment. To the surprise of the PLA, India deployed close to two full divisions, plus a few quickly mobile formations, thus making about 40,000 to 50,000 troops available for any action on the mountains. They were also equipped with light tanks, self-propelled howitzers and surface-to-air missiles. The IAF, too, came into play with the Rafale multirole fighters. Indications are that India is now determined to keep at least one division in eastern Ladakh, even if there is further disengagement. And, the Chinese are not backing off either. Even after the partial disengagement in February, Chinese tank formations have been relocated to a staging area near Rudok.

The deployment and tactical wargames have also revealed that the PLA infantry has not yet been fully mechanised. There are also problems of standardisation of equipment which can create logistical nightmares during operations. “The PLA is yet to complete the task of mechanisation,” contrary to what Xi had said in 2017, said General (retd) Robert Spalding, a US expert on the PLA. All the same, the Ladakh action, said China expert Avinash Godbole, “may have been based on the PLA’s calculations of its ability to change status quo at multiple locations at a single stroke, especially when India was faced with the Covid crisis, lockdown and the consequent economic slowdown.’’

India’s countermoves apparently were not on the lines that the PLA’s theatre commanders had war-gamed for. Initially, India went for mirror deployment of forces, which was defensive in nature. “Since April 2020, both the PLA and the Indian Army managed to surprise each other with the scale and the speed of their military build-up in the remote Ladakh region as also in each side’s willingness to test the other’s threshold,” wrote Colonel Abhishek Singh, who has served on the LAC, in a recent paper for the Delhi-based Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS). “The Chinese did not hesitate in raising the ante by their violent actions in the Galwan Valley in June 2020, and India’s preemptive occupation of the Kailash Range in end August 2020 was an equally brazen response to China’s continued belligerence.”

The Indian Army’s Kailash Range action was not on the lines that the Chinese had anticipated. “It found the PLA ill-equipped to oust us from those positions,” said an officer who served in Ladakh.

The PLA is learnt to have been surprised by India’s capability to quickly mobilise troops and induct them in forward areas. “The roads and bridges built on the Indian side since 2003-04 were found to have enabled the Indian formations to not only quickly reach the flashpoints, but also deploy themselves in offensive posture in mirror formations against the PLA,” said an intelligence officer.

Apparently, one area where both sides seem to have found problems is in cross-terrain movement. “They have found that they can quickly reach the front, but moving from one hill feature to another laterally was not satisfactory,” said the officer. “When we occupied certain hill features, they could not move troops laterally and had to bring troops from the rear to counter us. Use of helicopters was also limited. On this count, we seem to be better equipped with our Siachen-hardened heli squadrons.”

The anti-India mobilisation is also learnt to have exposed weak links in the PLA’s ability to mobilise rapidly. If they want to compete with the US, “they first need transport aircraft, rapid response forces and power projection units,” pointed out Srikanth Kondapalli, a leading China expert at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. The mobilisation also exposed a “lack of synergy between the human element (soldier) and its modernisation plans,” added seasoned Tibetologist Claude Arpi. Several hundred troops, trained in Tibet’s Qinghai plateau, were found to have been less acclimatised; they had to be often supported with portable oxygen containers, and were rotated faster than Indian troops. There are indications that the PLA is reviewing its human resource policy totally, so much so that it has frozen all recruitment. “There was no recruitment last year,” said an intelligence officer.

All the same, it is not yet time for India to rest on the laurels. “China is a fast learner, and the Chinese will surely rectify what went wrong in Ladakh, even if they appear to have not gained much from the adventure on the ground,’’ said Arpi. The PLA has been building field hospitals not far from the forward areas and are also procuring additional snow mobility vehicles, indicating that the troops are here to stay. The PLA camps at Shiquanhe and Rudok, around 40km and 80km from the border respectively, have permanent winter accommodation, well equipped medical facilities, power supply and mobile connectivity which enable troops to stay for longer periods. But the Indian side is not as well equipped, with troops largely dependent on diesel generators for electricity and having patchy communication networks.

“This year, China is also planning for smart borders, and the allocation of nearly $29 billion for Tibet in its 14th Five Year plan indicates certain thrust areas, including converting certain civil infrastructure such as airports, fuel depots and even hospitals for dual (civil and military) use,” said a China watcher in the Indian Army’s operations directorate.

In fact, “the exploitation of civil sector resources to support and boost the capabilities of the PLA is not a new practice,” wrote Major General D.S. Rana, provost marshal of the Indian Army, in a recent paper published by CLAWS. “Instead, it is now a streamlined procedure and part of China’s recent and pivotal national strategy, named as military-civil fusion (MCF). The role of private companies supporting PLA mobilisation and subsequently sustaining troops in harsh conditions during the ongoing standoff in eastern Ladakh has been widely publicised by the Chinese state media.

The same is also frequently evident in China’s military-industrial complex. Recently, China conducted an exercise in which the workers in car factories were mobilised by the PLA. The exercise simulated a requisition order for large platform trailers. Car factories temporarily reoriented their equipment and staff towards converting 20-tonne semi-trailer trucks into larger and sturdier vehicles, capable of transporting a 40-tonne Type 59 main battle tank within eight hours for deployment of heavy armoured vehicles in border areas.”

China is also planning to run bullet trains across Tibet almost till the Arunachal Pradesh border in the next two months, though the plans to connect Tibet to the mainland with high-speed trains have not taken off. The PLA is learnt to be encouraging villagers from elsewhere in China to move and settle closer to the LAC while the Indian side is getting depopulated. “They never had so many people there before,” said Naravane. “They need to build additional infrastructure to house the additional people.”

Indeed, Chinese experts dismiss the claims. “Whether it is military modernisation goals, centenary goals or the TMO, China is keeping strategic focus on its own development, which is in line with the consensus among the CPC leadership,’’ said Xie Chao, assistant professor at the Institute for International and Area Studies at Tsinghua University, Beijing. He pointed out that China does not set goals and follow courses to achieve them in competition with another country. “Goals are set as per the natural course of events, and there is no need to make a specific plan to exceed someone. This also means that making progress on its goals, step by step, will make the PLA a world class force,” he said. However, he admitted that such goals are reviewed by the CPC regularly and publicly.

Indian analysts expect a thorough review of the goals around July 1, when the CPC will officially mark a century. Though the Covid-19 pandemic has dulled the celebratory mood of the centenary, major announcements about economic, strategic and military goals are expected. “The entire army needs to strengthen its performance so as to do a good job of ensuring a good start to the 14th plan, and of the 100th anniversary of the founding of the party,” Xi recently told the PLA leadership.

Observers in Delhi say that signs of an aggressive military policy have been there ever since Xi sidelined Li. Xi has been, of late, moving his Tibet commanders to positions of power and influence in the central leadership. Thus, General Zhao Zongqi, who headed the western command during the Galwan clashes and retired last December, has been appointed deputy chairman of the foreign affairs committee, an influential body of the National People’s Congress.

Two other PLA generals, too, found their way into the NPC, displaying the growing influence of the PLA in political decision-making. General Wang Ning, who was heading the Armed Police Forces, was appointed deputy chairman of the NPC Committee on Constitution and Law. General Zheng Weiping, former political commissar of the Strategic Support Forces, is now deputy chairman of the NPC Committee for Education, Science, Culture and Health. “The PLA presence in the parliamentary body will ensure sharper focus on military requirements,” said Arpi.

Chinese strategic experts, however, deny all these. The Chinese strategic culture urges rulers to “try peaceful means before resorting to force,” said Xie. “The principle is ‘xian li hou bing’, which literally means prioritising diplomatic negotiations and resorting to military forces are equally important in achieving strategic goals.”

With R. Prasannan