The year is 1961, when the US and the USSR are at the height of the Cold War, and all attention is focused on space. In October 1957, the Soviets had launched Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite, into the earth’s orbit, thus gaining a distinct advantage in the ‘race for space’. The next year, to regain lost ground, president Dwight D. Eisenhower signed an order for the creation of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). At NASA’s Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory in Hampton, Virginia, there was a segregated west side whose existence not many NASA employees knew of. This was where the coloured women—or the ‘West Computers’—who did much of the space agency’s complex mathematical equations, sat.

Theodore Melfi’s biographical drama, Hidden Figures (2016)—about the lives of three path-breaking West Computers—begins after the Soviet Union’s Vostok 3KA-2 successfully orbits the earth in March 1961, carrying a mannequin and a dog. There is a note of desperation in the voice of Al Harrison, the head of NASA’s Space Task Group, as he demands a human computer who is good with analytical geometry to do the agency’s orbital calculations. A missive is sent to the west side, and Katherine Coleman Goble Johnson becomes the first West Computer to work with the Space Task Group. As she enters a room full of white men who pay her scant regard, a trash bin is thrust at her. “This wasn’t cleared yesterday,” says one of the men. “Oh no, I’m not here to…,” she tries explaining, but the man has already left.

Meanwhile, nearly 5,000 miles away, the Russians make history when Yuri Gagarin became the first cosmonaut to orbit earth in April 1961. By this time, everybody in the US is paying close attention to the space race, the interest amplified by the new medium of television. The country’s space programme is being heavily covered by the media, with the American astronauts portrayed as national heroes on a crusade against the “commie villains”. It is almost with a sense of relief that NASA successfully put Alan Shepard in space a month later. For decades, no one would know the full extent of the role played by the West Computers in helping NASA do this.

Sixty years later, the action has shifted from space to Mars. February 18, 2021 is a tense day at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. It is the day when the space agency’s fifth rover to Mars, Perseverance, which launched in July 2020, is landing on the Red Planet. The team members of the Mars 2020 mission are spread across eight locations in the vast 177-acre campus of the JPL. Some are in the mission control room. The EDL (Entry Descent Landing) operations team is sitting upstairs. Across the hall is the surface mission control room, whose scientists are waiting to take over as soon as Perseverance’s wheels touch the ground of Mars. Then there is the Dark Room, which is the heart of NASA’s deep space networks. It is from where the spacecraft “phones home” to NASA from across the solar system.

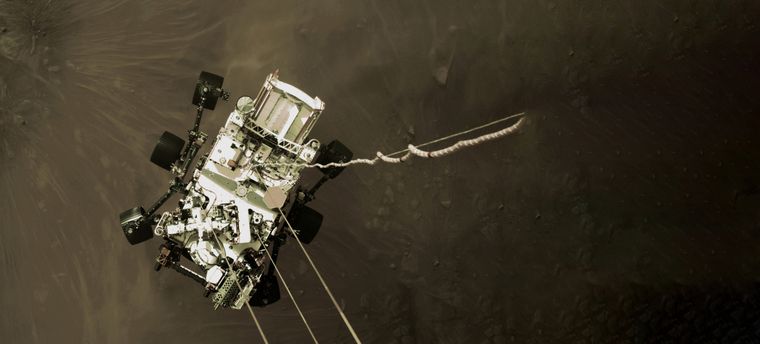

Landing on the surface of Mars is an extremely complex process. After the cruise stage separation (where Perseverance separates from the cruise stage hardware that it relied on to get it to the Martian atmosphere), the ground team at NASA will turn the transmitter off. Then the rover is left on its own to execute the manoeuvres necessary for the entry, descent and landing on Mars, which takes approximately seven minutes, known famously as the “seven minutes of terror”. In this time, many things must go right with sub-second timing accuracy; Perseverance must read over five lakh lines of code autonomously. The rover, which comes hurtling into the Martian atmosphere at 12,000 miles per hour, must first slow down to two miles per hour at landing. Once it is slow enough, it deploys a supersonic parachute to slow it down further. After Perseverance zeroes in on the place where it wants to land, it jettisons the parachute and lights up its rockets which help steer it to the landing spot.

Usha Guduri, the planning and sequencing subsystem manager for the Mars 2020 mission, had prepared meticulously for landing day—the culmination of five years of hard work. She had even got her daughter, four-and-a-half-year-old Moksha, a landing day present—a Wall-E soft toy. They were all at home, wearing NASA landing T-shirts, and watching the nail-biting live stream. Her parents had video-called her earlier from Hyderabad. Her husband Praveen was recording her reaction to the moment when the mission commentator announced “Tango delta nominal”, indicating Perseverance’s safe landing on Mars. “I had turned all red,” Usha remembers. “Once the landing happened, I was in jubilant tears. Moksha was jumping up and down.”

When Usha joined the Mars 2020 project in April 2016 to lead one of the six subsystems handling the ground software of the mission, she was five months pregnant with Moksha. On the day she had to present the preliminary design for the subsystem at a key NASA project meeting she went into labour. As her presentation came up, she signalled her colleague to take over and rushed to the hospital. When she came back after her maternity leave, things had to be ramped up fast. From two people, she built her team to over 30 members. While other teams are responsible for several aspects of handling the telemetry from the rover—including images, video and audio files—Usha’s team is responsible for the input that goes into the spacecraft.

“I always tell my team that we need to understand how privileged we are,” she says. “Whatever comes out of our tools gets into the spacecraft. With NASA missions, we cannot afford to build very fancy tools because we work under extremely tight time constraints. No matter what happens, you have to meet your deadline because if you miss the launch window for sending a spacecraft to Mars, then you have to wait for another two years to send it.”

The Mars 2020 mission is expected to be a game-changer for NASA’s Mars programme because this is the first time a rover will be sent there as the first step to bringing back samples from Mars, so that scientists can investigate the astrobiology on the planet to find out whether life ever existed there. Perseverance will self-drive on the surface of Mars for 200m a day, building a map of the terrain that it covers. It will then collect samples of Martian rock and sand, put them in small tubes, seal them and set them in designated places on the planet. Another mission in 2030 will collect the samples and bring them back to earth.

The technology with which Perseverance is outfitted is extremely complex, says Usha. This includes MOXIE; a testing method for producing oxygen from the Martian atmosphere; Ingenuity, the first-powered helicopter on Mars; and TRN or terrain relative navigation. Perseverance is the first mission that used TRN to land “with its eyes open” at a precise location on the Jezero Crater (believed to be home to an ancient river delta), which contains some of the most beautifully preserved delta deposits in Mars, and therefore, would have been an ideal place for micro-organisms to thrive. This also means that the loose sand and the hills and boulders of the crater made it an extremely dangerous place to land a rover. “We were completely mind-blown by how accurately the system worked,” says Usha. “On the landing map, you would see hazardous areas everywhere, and there was this tiny safe spot where the rover could land; it landed there beautifully.”

By now, Perseverance has taken more than 75,000 images of Mars and its microphones have recorded the first audio soundtracks of Mars—a muffled wind that sounds like what one might hear “listening to a sea shell or having a hand cupped over the ear”. On June 1, Perseverance left its landing site. Until then, it had been undergoing systems tests or commissioning. Over the next few months, the rover will explore a 4 sqkm patch of the crater floor.

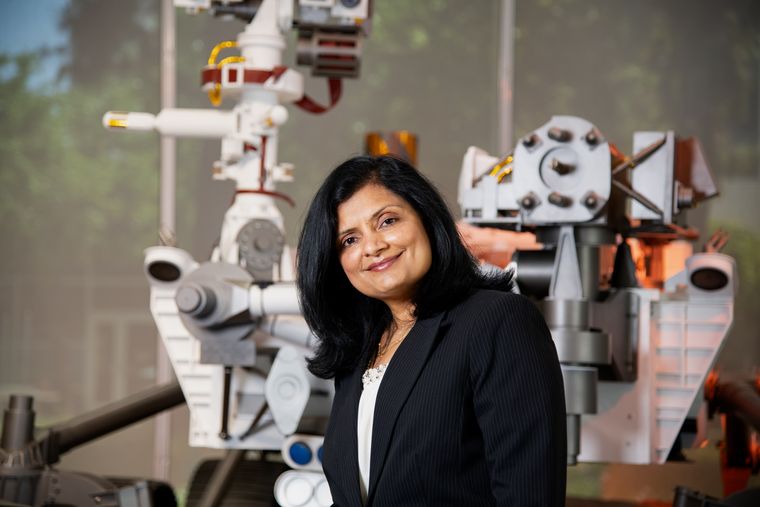

It is easy to detect the passion in Usha’s voice. Much like the West Computers of the 1960s, what these women do is not for the glory but for the joy. As Nagin Cox, 56, a systems engineer who is the deputy team lead of the engineering operations team on the Mars 2020 mission, once said, “I have never expected that anyone would remember my name. But I’m hopeful they will remember my missions.” The Bengaluru-born Nagin, who has won the NASA exceptional achievement medal twice, has been part of enough memorable missions for her hope to be realised. She was also a member of the teams that worked on previous Mars rovers like Spirit, Opportunity and Curiosity. She even has an asteroid named after her.

Nagin wanted to work at NASA-JPL from the age of 14. When she got there in 1993, for a long time, she wrote the acronym IWWTWTF at the top right-hand corner of every notebook. It stood for ‘I was willing to wash the floors’—a reminder of just how much she wanted to work at NASA. She had been too young to remember the Apollo moon landing, but she had seen some of the later Apollo and early space shuttle missions. That is when she realised that these landmarks in space exploration brought people together in a way few things did. “There were not even VCRs those days,” she remembers. “Because you could not record it, everybody would come together to watch [these historic space missions]. After the Apollo moon landing, nobody said ‘Americans’ landed on the moon. Everybody said ‘we’ landed on the moon.” Even as a little kid, she realised that there were big challenges that we could solve together—like curing diseases or stopping wars. Space, she saw, was one of them. Shows like Star Trek and Carl Sagan’s Cosmos further fuelled her interest in space. Another insight came when she saw that astronauts had only gone as far as the moon. But there were robotic spacecrafts that were sending back outstanding images from places as far as Jupiter and Saturn. Her goal was set: she was going to work on robotic missions at NASA-JPL. The destination had been decided. Now, only the journey remained.

Since the days of the West Computers, things at NASA have progressed admirably. The first American woman in space, Sally Ride, flew aboard the Space Shuttle STS-7 in June 1983. The 2013 astronaut class was the first with an equal number of men and women. NASA astronauts Jessica Meir and Christina Koch completed the first all-female spacewalk in October 2019. Several women have served in important roles at NASA Langley, including Lesa Roe, who was its centre director; Ellen Stofan, who served as chief scientist; and Elizabeth Robinson, who served as chief financial officer.

Still, it is not easy for women from ethnic minorities in high-tech industries in the US.

“As a coloured woman, I felt unwelcome when I joined the workforce in 2005 as a military contractor,” says Yogita Shah, an avionics domain lead with the Mars 2020 mission. She talks about feeling intimidated at meetings, especially when she was working in the aerospace industry, where she would be the only woman of colour in a room dominated by white men. “I used to feel like nobody looked at me,” she says. “It is not a pleasant feeling. I started doubting myself. Am I doing something wrong? Even after working hard, as a woman of colour, I have to prove myself every single day.” Sometimes, when she got passed over for promotions that she felt she deserved, she would find herself wondering about how much easier things would have been if only she had been born in the US.

Instead, Yogita had been born in Aurangabad. She did her schooling in different parts of Maharashtra when her father, a bank employee, got transferred every three or four years. Yogita grew up hearing him talk about how, if only he had a son, he would have made him an engineer. That is why, in her third grade essay, she wrote that she wanted to be an engineer when she grew up; she had no idea what an engineer did, though.

In the India of the 1980s and 1990s, women were discouraged from pursuing higher education, remembers Yogita. From a young age, she knew she would have to fight against this unfairness and injustice, because women, too, she felt, deserved freedom. When she joined the Government Engineering College at Aurangabad, members of her community were skeptical. “Why spend so much money on her education when eventually, you will have to get her married?” they asked her parents. Ironically, it was marriage that took Yogita to America and, ultimately, to NASA-JPL, after a 11-year stint with the aerospace industry.

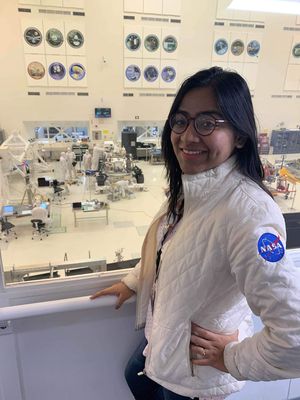

Priyanka Srivastava, 28, who was a systems engineer with the Mars 2020 mission and is now part of the Europa Clipper, NASA’s interplanetary mission, is one of the younger Indian women at NASA-JPL for whom it has largely been smooth sailing. “I have been extremely lucky to be part of great teams,” she says. “All my group supervisors have been women. In the Europa mission, for example, there is a 60-40 ratio between men and women. The lead chief engineer in the project is a woman. NASA is also making an effort to bridge the pay gap between men and women.”

She says it has been a privilege to work at NASA-JPL. “Because everyone is committed to working towards the same objectives, all the meetings are very goal-oriented,” she says. “At the same time, if you hang around by the water fountain, you will hear people discussing everything from their latest hiking trip to their favourite restaurants. This passion in diverse interests triggers so much creativity at NASA.”

Although Priyanka was born in the US, she spent most of her growing-up years in Lucknow. When Yogita did her electrical engineering in the 1980s, there were six women in her class of 80. By the time it came to Priyanka in the 2000s, in her electronics and communications engineering class at Panjab University, 25 of the 40 students were women. This generational progress goes back, beyond Nagin, Yogita, Usha and Priyanka, to almost the beginning of NASA.

The privileges these women enjoy today have been bought for them with the struggles of others who came before them, like Katherine Johnson, who did the trajectory analysis for Shepard’s space flight. But the real contribution of the brilliant mathematician, who was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2015, was in 1962, during America’s first manned orbital mission, described in the final scene of Hidden Figures. The IBM computers, linked with tracking stations around the world because of the highly complex nature of the mission, have been programmed with the orbital equations that mapped astronaut John Glenn’s flight on the Friendship 7 capsule from liftoff to splashdown. On the day of the launch, Harrison, the head of the Space Task Group, realises that the landing coordinates provided by IBM are not tallying. A call is made to Cape Canaveral, where Glenn is making the last minute preparations for the flight. When the problem is explained to him, Glenn is believed to have famously said, “Let’s get the girl (referring to Katherine) to check the numbers. If she says they are good, I’m ready to go.” A messenger is sent to the west side, where the West Computers, like the rest of the nation, is watching with bated breath. All eyes are on Katherine as she quickly does the math and comes up with the correct landing coordinates. Back at the Space Task Group, she hands over the document and the door shuts in her face. As she stands outside wondering what to do, Harrison opens the door. “Get in here,” he tells her. When she sailed through that door, she did not just make history, she opened the way for countless other women at NASA to do so.