Sometime before mayhem descended and much before the crowd was denounced as one of the criminals, the nervous anger that slithered through it had begun to dissipate.

But then, the firing started.

It was February 4, 1922. A crowd of volunteers who identified themselves as Mahatma Gandhi’s satyagrahis, the ones who were following his instructions on the non-cooperation movement (NCM), had marched to the Chaura police station. The event gets its name from the railway station of Chauri-Chaura that lay behind the police station. The name was a portmanteau of two adjacent villages that lay some 23km from Gorakhpur city in eastern Uttar Pradesh.

Three days earlier, on February 1, three satyagrahis—Bhagwan Ahir, Ramrup Barai and Mahadeo—were beaten up on the orders of Gupteshwar Singh, the sub-inspector of the station, when they were picketing Mundera Bazaar, a prosperous market of pulses, raw sugar and rice. Of the three, Ahir received the most severe beatings.

Ahir had been a soldier in World War 1 for two years and had been posted at Basra. The policeman’s anger against Ahir was the greatest for he drew a government pension as an ex-soldier and yet, as Singh perceived, he wanted to overthrow the same government.

Kallan Ahmed, the grandson of Nazar Ali, one of the leaders of the movement, who came from the village of Dumri Khurd—which was the epicentre of the political activity in the region—said: “Ahir was a strong man. But so merciless was the beating that he struggled to get back home.”

Over the next three days, a spate of meetings was held, and it was decided that the volunteers would march to the police station to ask Gupteshwar Singh for an explanation for their behaviour. Letters were sent out to neighbouring villages in an approximately 10km radius, asking volunteers to gather at Dumri Khurd on the morning of February 4. It was at this village that a mandal committee of the NCM had been formed the previous month—on January 13, 1922.

Ironically, some of these meetings were held in front of the home of Shikari—the approver deemed most reliable by the courts. Shikari’s son Ashik Ali still lives in Dumri Khurd and is not free of the taint of the past. “I know nothing of the event,” he told THE WEEK.

On the morning of February 4, volunteers, including Shikari, went from door to door in the village asking for contributions of jaggery and roasted rice–refreshment for the volunteers. The meeting venue was a threshing ground in the village. (This is disputed by the elderly residents of Dumri Khurd, who say it was held in an orchard of mango, jackfruit and shisham trees in the local cemetery). Here, sacks had been laid out for volunteers to sit on, in groups of six. Ali made a speech extolling the volunteers. He also said that anyone who left midway would be guilty of defiling their religion. Not a single volunteer left.

Historical accounts of that march, which started sometime between 1:30pm and 2:00pm, indicates that just like the meeting, it was also an orderly affair. As the crowd marched to the police station, it swelled as passersby joined in. Though the speculation about the strength of the crowd varies, the High Court judgment in the case puts it between 1,000 to 1,500.

At the police station, the volunteers spoke to Singh. It was, by some accounts, courteous, with the sub-inspector going as far as saying that Ahir was like a brother to him. With the matter resolved, the crowd moved on as planned to picket Mundera Bazaar.

“And then someone said to Singh: ‘What a shameful act this is. You being a Thakur bowing to these low-caste men’,” recalls Sharda Nand Yadav, the great-grandson of Bikram Ahir, one of the 19 men hanged for the violence that followed.

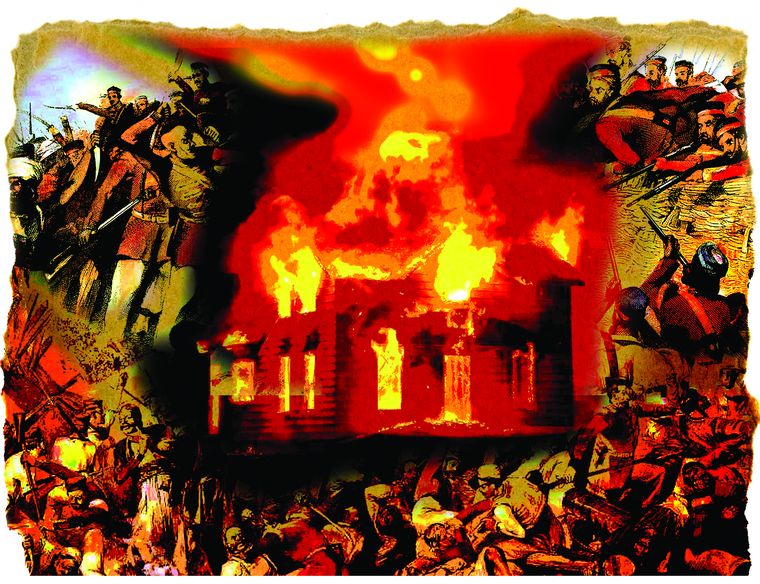

At this taunt, Singh ordered his chowkidars to hit their lathis on the ground, and the armed police to fire in the air. The large part of the crowd which had moved ahead sensed danger and returned to pelt the police station with ballast picked up from the railway track. A lathi-charge ensued and the police then fired into the crowd—killing at least three and injuring many others. This further enraged the crowd. Outnumbered, the police retreated into the police station. Some of the volunteers seized kerosene oil from the market and set the police station on fire. Other volunteers cut off the telegraph wires of the local post office to prevent the news from spreading.

Twenty-two policemen (including constables and chowkidars) died in the fire. One severely injured chowkidar died a day later.

Also read

- Ahead of Aug 15, Vice President Venkaiah Naidu takes stock of India’s long journey

- When ordinary Indians took on the British

- Fearlessness, discipline, communal harmony―the big lessons from Kakori martyrs

- How 356 sepoys of Bhopal contingent defied begum, British to set up a parallel govt

- Attingal revolt was among earliest acts of resistance against British imperialism

- Anjengo’s Eliza

- The real story behind Sanyasi rebellion

- Revisiting sites that shaped Indian polity

An Indian National Congress report of an inquiry into the incident would later note: “Twenty-three men were beaten to death and all except a few of them burned. The thana was set on fire and the men who attempted to escape were driven back into it.” Yet, even in that fury, the volunteers offered safe passage to women and children (including the pregnant wife of Singh).

The Gorakhpur Sessions Court said this about the killings: “The burning of the victims took place while some of them were still alive.… They poured kerosene oil on the corpses and set fire to them.” It would also link the event directly to the non-cooperation movement, “in the sense that if it had not been for the movement, it could not possibly have occurred”. Gandhi was central to the event for he called for the NCM and then stopped it. On February 12, Gandhi wrote in Navjivan an article titled, ‘Crime of Gorakhpur’. Four days later, in Young India, he called the violence the “deadly poison from Chauri Chaura”.

The Congress Working Committee in its meeting in Bardoli, Gujarat, on February 11-12, 1922, passed resolutions condemning the “inhuman conduct of the mob at Chauri Chaura”, tendered its sympathy to the families of the deceased policemen and called off the non-cooperation movement as “the atmosphere in the country [was] not non-violent enough for mass civil disobedience”.

There was nothing on the atrocities that the police had forced on the volunteers both before and after the incident. It was labelled a “kand”—a word for an abominable incident. The police launched a massive hunt for the perpetrators of the violence. Womenfolk scurried away to their paternal homes.

“Chauri Chaura” became a metaphor for shame. Though its enormity could be gauged by the fact that the poorest had risen to commit an audacious act against a police force.

It remains somewhat of a mystery why the distress that lay beneath the event at Chauri Chaura was not recorded then by even Munshi Premchand—a prolific writer who captured the agony of the peasantry in searing detail. The department of history at Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Gorakhpur University (DDU) was set up in 1958. Yet, till very recently it produced nothing of worth on Chauri Chaura.

Then in 2021, the Union government and the Uttar Pradesh state government announced that the centenary of the event would be celebrated with year-long celebrations. On January 25, at the Constitutional Club of India, New Delhi, was released a Hindi book titled Chauri Chaura, A Re-evaluation: A Local Event of National Significance edited by Himanshu Chaturvedi, a professor of history at DDU.

Chaturvedi said: “In history, it is not the event but its narration that is important. And the narrative on Chauri Chaura has been misguided and has divided [the people behind it] into [different] castes. Terming it subaltern is demeaning. The people who participated in it stood for the nation.”

Chauri Chaura was, in fact, a fight of the “little people” led by Muslims, dalits and backward classes. Its leaders were men who were not even accorded the respect of having their full names listed in court documents. The same records prefixed Gupteshwar Singh’s name with “Thakur”.

Shahid Amin’s Event, Metaphor, Memory: Chauri-Chaura, 1922-1992 (1995), is the first academic work on the subject. In its prologue, Amin, a retired professor of history from Delhi University, describes it as the story of “anonymous characters from a self-defining event of Gandhian nationalism”.

For Amin, the most fascinating part of his research for the book was the “strong presence” of Gandhi as the “author” of the movement. “Without his visit to Gorakhpur the preceding year, and the electric excitement it generated, the kind of mobilisation that happened would not have been possible,” he said. Yet, on February 4, 2021, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi virtually inaugurated the centenary celebrations at the Chauri Chaura memorial, he omitted any reference to Gandhi.

Subhash Chandra Kushwaha’s is the second published book on the event. Written, originally in Hindi (in 2014), the book’s English version Chauri Chaura: Revolt and Freedom Struggle (2021) draws material from the doctoral thesis of Anil Kumar Shrivastava and a booklet written by Ramamurti—a Gandhian from Gorakhpur.

Kushwaha is dismissive of the contention that martyrs have no castes, pointing out that the two high caste men (among the 19 who were hanged) were accorded the respect of their surnames while the other 17 were not.

“Characters from specific castes have been brought in to claim that this was a movement of all,” he said.

Kushwaha believes that the government’s efforts to recast the movement in a light that links it to the idols it cherishes are bound to fail. “Claiming a role in what was done by people from the margins of society is a distortion of history. That is just an election ploy,” he said.

He further explains this warping of history with reference to a filmmaker who wanted to know who the heroes of the movement were around which a movie on Chauri Chaura should revolve. “I said Nazar Ali and Lal Muhammed. The filmmaker said that was not possible in the current climate,” said Kushwaha.

Nazar Ali was an ex-soldier and Lal Muhammed was a seller of coarse clothes. Both were wrestlers—an important fact as news of activities planned for the non-cooperation movement often and most swiftly travelled through the akharas, which were meeting points for men from different villages in the region.

Mohammed Mainuddin, the great-grandson of Lal Muhammed said that the fact that his great-grandfather was “the biggest hero” of the event had brought no respect to the family. The Chauri Chaura Shaheed Smarak also leaves one confused. It has just two stone plaques engraved in Hindi and English about the details of the event. Many of these details are incorrect.

As one enters the Smarak, to the left are painted pictures of the “shaheeds” of Chauri Chaura. All bear a generic look, distinguished only by a Gandhian cap here or a moustache there. At the centre of the Smarak is a reddish-brown stone monolith with flanking plaques bearing the names of the 19 martyrs who were hanged. Around it is a fountain—its water smelly and thick with algae. At one place on a brightly painted wall is written ‘Shaheed Smarak—Chauri Chaura Kand—February 1922’, next to a drawing of three nooses. Notice the use of that odious word kand and the missing date.

The Smarak also has a library—with not one book on Chauri Chaura, except one copy of a booklet written, just in time for the February 4 kick-off, by Manoj Kumar Gautam, the deputy director of a Buddhist Museum in the district. The only historical document available in the library is a copy of the High Court judgment on the case. The only guide available to walk visitors through this is Lal Babu, the chowkidar, who admits to not having read anything on Chauri Chaura. “I only know what I have heard,” he said.

The District Magistrate of Gorakhpur, K. Vijayendra Pandian, said that the government had acquired two acres adjacent to the memorial to build, among other things, an amphitheatre, and a digital library. The descendants of Chauri Chaura’s “political sufferers”, as Sharda Nand Yadav calls them, have more modest demands—such as a small memorial in Dumri Khurd, a stone plaque listing the names of not only the martyrs but also the many others who played their roles in the movement, and some literature on it for the young to read.

There have been some attempts at reviving the memories of the movement. However, four generations down, the glories of martyrdom seem amorphous. In Rajdhani lives Akhtar Ali, the great-grandson of Abdullah, who was a key figure in the event. It is his name that figures in the title of the case that was filed at the sessions court—King-Emperor versus Abdullah and others.

“It is not a question of glory when all you are struggling for is two meals a day,” said Akhtar Ali who works on construction sites in different states. It was that sense of being left with nothing that was coursing through the peasantry of Avadh in the colonial period.

Chandra Bhushan Ankur, professor of modern history at DDU, drew a parallel between the distress of the peasantry under the British and of farmers today. “An imperial ruler, a native landlord and no control over one’s land—that lay at the heart of the distress then,” he said. “Now, one of the fears is that corporates will take over farming and there will be no safety nets.”

Mohammed Sajjad, professor of modern Indian history at Aligarh Muslim University, said today’s Indian peasantry is more assertive unlike the one in British India. “The [current] government is pushing them into a corner, hoping for them to indulge in violence so that it can respond likewise,” said Sajjad. “The peasantry was provoked in Chauri Chaura—but that fact though known was not popularised.”

Hundred years after Chauri Chaura, its subdued voices have only grown louder. But its lessons seem to have grown feebler.

Or, perhaps the nation’s collective will to listen has grown weaker.

Note: The details of events, unless otherwise specified, are from Shahid Amin and Subhash Chandra Kushwaha’s books. The names of people and places are as they appear in the judgment of the sessions court.