The National Directorate of Security, Afghanistan’s intelligence agency, got a tip-off from India’s Research and Analysis Wing last November about a Chinese spy ring in Kabul. The tip-off led the police to the apartment of a Chinese national who had come to Afghanistan three years ago to work in a Chinese company’s road-building project in Bamiyan, was teaching Chinese in a private school in Kabul, and also exporting pine nuts to Shanghai. The teacher-trader’s arrest in December led to the busting of a spy ring that involved 10 Chinese nationals living in Kabul, and an Afghan who ran the school.

That was perhaps the last hurrah one heard from India in the war-torn country. Though Vice President Amrullah Saleh, himself a former spy, protested to Beijing, China wanted its nationals back. Within days, the 10 Chinese nationals were put on a chartered flight without being charged, and sent home.

The tables have since turned, too dramatically. China’s diplomats are very much in their mission in Kabul now, even as their Pakistani friends are cheering the Taliban takeover of the country’s capital. India’s was among the first missions that shut shop and left, despite having spent $3 billion on building dams, roads, bridges, power stations, hospitals, schools and even the national parliament building.

Indeed, the return of the Taliban is bringing back memories of the troubled 1990s when, inspired by the Taliban and armed by Pakistan, insurgency peaked in India’s Kashmir, bombs went off in India’s shrines and markets, an airplane was hijacked to Kandahar, and terrorists were escorted to freedom.

While many are now worried about a resurgence of religious terror in the region, India’s security experts are not so concerned. “With the line of control fenced, and an enhanced anti-infiltration grid of sensors and guards in place, and the presence of Rashtriya Rifles, terror inflow will no longer be easy,” said Lt.-Gen. Mohinder Puri, former deputy chief of Army who had commanded a division in the 1999 Kargil war.

There are political reasons, too—signs are in the air that Taliban 2.0 may turn out to be moderate, allow civil freedoms, let women go to work, and girls go to school. They have even waved an olive branch towards India and, as the foreign office claimed on August 31, their representatives dropped in at the Indian mission in Doha for a meeting—the first official contact that India had with the group.

The Taliban may share power with non-Pashtun tribes such as the Tajiks, the Uzbeks and the Hazaras, and may refrain from exporting religious toxin and terror. They may even discipline, under pressure from China and the rest of the world, the other freebooting terror groups such as the Haqqani network and the East Turkestan Islamic Movement that are currently active in Afghanistan.

India’s concern is no longer about the revival of terror, but is strategic and military. The Taliban is seeking to build a legitimate state system to the subcontinent’s northwest, from where India had been invaded scores of times since the days of Alexander. It was essentially to secure India by ensuring a friendly state there that the British fought two costly wars in the 19th century, played the Great Game in western Tibet and central Asia, and followed an aggressive frontier policy towards the Chinese empire.

Even after the British left, India stayed secure with a friendly regime in Kabul that did not allow Pakistan to have the strategic depth it coveted. Pakistan had to keep a good share of its army and air fleet near the Durand Line, the legitimacy of which had often been challenged by the Afghan Pashtuns, leaving India to enjoy military superiority against Pakistan. All that went for a toss when the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in 1979, bringing “the Cold War to our doorsteps,” as a distressed India Gandhi bluntly told old friend Premier Alexei Kosygin of the Soviet Union, and throwing the country into a civil war involving religious bigotry, tribal feuds, American dollars, CIA spies, ISI terror, and the Pakistan army.

The rout of the Russians a decade later and the break-up of the Soviet Union brought home the worst nightmares that all the great games of two centuries had sought to allay. Having gained strategic depth with a regime that it virtually controlled in Kabul, Pakistan unleashed a strategy of territorial infiltration and export of terror into Indian Kashmir.

The arrival of an angry America another decade later, seeking to avenge the plane-bombing of its World Trade Centre, changed all that. In the next two decades, as the Americans and the NATO forces hunted down terrorists and the Taliban, India invested heavily in Afghanistan. However, “India failed in building organic links by understanding the sectarian tendencies and tribal sensitivities,” said Prateek Joshi, a foreign policy researcher at Oxford. “Simply building roads and electricity connections did not help.” In short, India earned popular goodwill, but not strategic dividends.

Now with a bloodied and bruised America, with whom India had allied too closely in the last one and half decades, fleeing, the old strategic nightmares are returning to haunt India. Old pals Russians, having got closer to China first and now Pakistan, are no longer on the same page with India on Afghan and central Asian issues. That leaves India, which has neither territorial proximity with Afghanistan nor has shown the strategic will to get involved, with no powerful friend in the region.

Technically, India does have territorial proximity, and that poses the biggest strategic worry. The northwestern corner of Jammu and Kashmir, the Gilgit-Baltistan region, brushes against the borders of Afghanistan in the northwest, Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to the west, China’s Xinjiang to the east and northeast, the Kashmir Valley to the south, and Leh to the southeast.

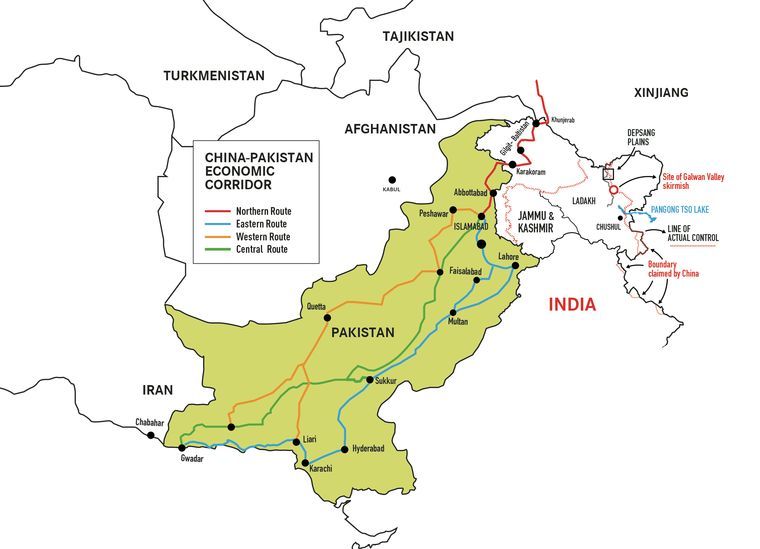

Under the direct rule of Islamabad, the region was made a full province early this year, in a tit for tat move against India converting its Jammu and Kashmir into another non-special state. A heavy share of India’s Army is poised on the line of control against occupied Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan, through which passes the ambitious China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Similarly, a large share of Pakistan’s army is poised on the other side of the line, threatening Indian Kashmir and the Ladakh region, which includes Kargil.

“[However,] with troops of about 40 countries being present in Afghanistan, there was no way Pakistan could have militarily menaced India in the last 20 years,” said an intelligence analyst. “Now that concern is gone; Pakistan is getting its strategic backyard under its control, and is free to do another Kargil-style misadventure.”

If China stayed away from Kargil 1999, leaving the field open to the US to put pressure on Pakistan, it may not do so in the event of another military confrontation. The People’s Liberation Army is already physically present not only in eastern Ladakh—putting pressure on the Indian Army since the Galwan crisis of last year—but also in the west, physically camping in the Pakistan-controlled Gilgit-Baltistan region, apparently involved in civil works such as widening the Karakoram highway. The highway is fast developing into the lifeline of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (one of the arms of Xi Jinping’s belt-and-road initiative), stretching all the way from China’s Xinjiang province to the Gwadar port on the Arabian Sea.

India might rest assured that its superior military strength can undo another Kargil threat, but the question is whether it can if China joins the game. “We have been talking of two-front war,” said noted strategic scholar Pravin Sawhney, co-author of the book Dragon on Our Doorstep and editor of the reputed Force magazine. “Actually, the two fronts have already amalgamated into one since August 2019. It is now a reinforced one-front threat that we are facing.” According to Sawhney, the military threat is already existing; with Kabul likely to join the axis, “the military threat is developing into a strategic threat.”

Many in the security circles believe that what happened in Galwan last year was a micro-level staging of the amalgamated threat. “Was it deployment and training of their [China’s] western theatre forces in a war-like scenario where Galwan was an overreach?” wondered IAF chief R.K.S. Bhadauria at a seminar last year. Or “Was it to fine-tune and enhance their military technologies and fill the gaps? Or was it just a misadventure that escalated?”

According to a source in the Army headquarters, it was the last. “Pakistan was apprehending some action by the Indian military into PoK, and it was at that stage that it got its Chinese friends to build up in Galwan, where 20 soldiers were killed in a scuffle without firearms,” he said. Now with Afghanistan under their control, “nothing prevents Beijing and Islamabad from scaling up the skirmish into a bold territorial invasion from the Karakoram sector,” he said. At least to secure their precious Belt-Road arm of the CPEC.

The widening of the Karakoram highway to four lanes (six on certain stretches) would enable not only factory trucks to move up and down the economic corridor, but also heavy military equipment. The highway cuts through the zone between Asia and the Indian subcontinent where China, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, India and Pakistan come within 250km of each other. Intelligence sources say that the PLA has built an alternate 8m- to 10m-wide road to Karakoram Pass to cut the distance from the pass to India’s strategic base at Daulat Beg Oldi (DBO). Satellites have picked up images of a 36km-long road near India’s Siachen glacier.

The Leh-Sasoma-Sasser Ridge crossing at Sasser La-Daulat Beg Oldi-Karakoram Pass, that separates Siachen from eastern Ladakh, is the main route that connects Leh with Chinese territory. A scene of action could be from the China-held Shaksgam Valley, which is in close proximity to the Karakoram highway that connects Gilgit-Baltistan to China’s Xinjiang province. Indian planners fear that the PLA will link the Lhasa-Kashgar highway to Karakoram Pass through the Shaksgam Pass, by tunnelling under the permafrost. Once the link is completed, the PLA will put pressure on DBO from the north so as to prevent the Indian Army from targeting the road.

The Indian Army is also apprehensive of Pakistan launching a localised offensive in north Ladakh, so as to gain territory that would provide depth to the CPEC. India could resist it with force, and even counter-attack elsewhere, but what if the Chinese, who are just a few hundred kilometres away, get involved? The Army is learnt to have war-gamed for three levels of threats from China—low, involving five to six divisions of about 10,000 troops each; medium, with eight to 12 divisions; and high, 18 to 20 divisions.

According to Sawhney, the PLA can mobilise up to 34 divisions on the Line of Actual Control, but “it would be difficult to bring more than 18 to 20 at the same time”, given the terrain difficulties. India’s war plan is based on a high-level threat, deploying nine mountain divisions and one infantry division, plus available elements of the 17 Mountain Strike Corps, the raising of which was in cold storage till late last year.

Sawhney estimates that China has built 16 airstrips on the Karakoram highway to enhance airlift capability, is laying optical fibre cable for communications from Rawalpindi to the Khunjerab pass, and has given the Pakistan military access to the high-resolution capability of its phase one BeiDou navigation system (equivalent to GPS).

Not only have the two armies fine-tuned their ways of operating together, but Skardu, which is just 170km by road and a few minutes by a war jet from Kargil, recently hosted a Chinese refueller aircraft. The two air forces have achieved a very high degree of equipment compatibility, interoperability and digital data linkage under the Shaheen series of exercises in PoK airspace. Indeed, India has fortified Ladakh since the Galwan misadventure with three additional divisions (approximately 60,000 troops), a squadron of T-90 tanks that can fire missiles, and armoured vehicles.

Though China has so far desisted from investing heavily in Afghanistan, that may no longer be the case. China has been engaging Afghanistan and Pakistan in a trilateral dialogue since early 2012, which has till date covered four rounds, the last in early June.

Also read

- Navtej Sarna: Taliban’s return is the next act of an unending Afghan tragedy

- 'The president fleeing destroyed us': Roya Heydari

- Repeating the mistakes of past wars in Afghanistan: William Dalrymple

- China eyes Afghanistan's trillion-dollar mineral deposits

- Afghan pop star Aryana Sayeed: We’re still in a society of backward-thinking individuals

“The US exit from Afghanistan has opened options for China in the region, both direct and through Pakistan, allowing it entry into Central Asia, a region it has been eyeing for long,” Bhadauria had warned nearly a year ago. If Iran, too, can be co-opted, that would give the BRI access to the Persian Gulf, allowing China to dominate not only the Af-Pak region, but also access to the Middle East. Despite their Shia-Sunni animosity, there are indications that Iran and Taliban have been talking for a while. Former Taliban leader Mullah Akhtar Mohammad Mansour was killed on May 21, 2016, by a US drone while he was returning after a long stay in Iran.

Pakistan, too, has been reaching out to Iran, an old friend of India that has been miffed in recent years with India’s strategic proximity to the US and Israel. While India is going ahead with its project in Chabahar port from where India hopes to get road access to Afghanistan, Pakistan, too, is reportedly asking the Iranians if they are interested in building a rail line between Chabahar and their own Gwadar. “Where would that leave our Chabahar project is anyone’s guess,” said a naval officer.

All the same, there are also experts who assure that there is no need for immediate alarm. “No one knows how the Taliban will react to its own people and what change it is talking about in its regime,” said former R&AW chief Vikram Sood. “But in the foreseeable future, Pakistan and China will be together on the strategic front. If Beijing puts a fast pedal on its expansionist policy, Kabul will be a central focus.”

There are also other fault lines that will open up further. “The Taliban will not divorce East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), which targets [China’s] Xinjiang,” where the communist state is persecuting Uighur Muslims. “Under such circumstances, investment, construction and operation of any economic corridor into Afghanistan will be risky,” he said.

Even Pakistan’s hold on the Taliban could prove tenuous, given that it is under pressure from China to rein in the Pakistan Taliban and the ETIM.

There are also uncertainties arising from Pakistan’s inability to secure Chinese projects. In July, nine Chinese nationals were killed in an explosion near the Dasu hydropower project, which is part of the CPEC. Another attack took place in Gwadar, in restive Balochistan.

These incidents have slowed down Chinese investment. Given such uncertainties in Pakistan itself, many believe that China will think twice before plunging into Afghanistan in Pakistan’s company. “I do not see China taking care of two basket case economies,” said Amar Sinha, former ambassador to Afghanistan. “China wants stability, peace, moderation in the region for its BRI dreams to fructify.”

Moreover, there are indications that all is not lost for India in Afghanistan. “Currently, the Taliban has no capabilities,” said Colonel S.C. Tyagi, author of Kargil Victory: Battles from Peak to Peak. “It wants to get legitimacy first. Yes, a nexus may develop with China in the long run, but we should use the goodwill we have in Afghanistan to prevent it.”

Lt.-Gen. C.A Krishnan, former deputy chief of Army, thinks that the possibility of an axis between Pakistan, Taliban-ruled Afghanistan and China against India is remote. “Afghanistan’s strategic assistance to Pakistan can at best be in the form of giving them an assurance of no threat from Pakistan’s western borders,” he said. “In fact, with the US pulling out of Afghanistan and Taliban snatching power, there is a possibility that China’s and Pakistan’s headaches in the region will increase. Beyond a sense of satisfaction about setting scores with the US and making it look small, Russia and China will be suspicious of the Taliban.”

Moreover, if at all a nexus threatens to develop, many believe that active diplomacy by India should be able to neutralise it. “India should reach out to the Taliban and make it clear that it will not walk away from the huge investments it has made in that country,” said former R&AW chief A.S. Dulat. “Just because the Americans have walked away, we need not copy them. The Americans are too far away, but we are too close for comfort. We need to find a way to stay and deal with them. And if Pakistan has so much control over the Taliban already, as we fear, that is all the more reason to engage them diplomatically.”

The ball, in other words, is in the diplomats’ court, not the military’s.