After reading his own obituary in a newspaper, Mark Twain said, “the news of my death is grossly exaggerated”. Similarly, having been told about the disappearance of Buddhism in the land of its birth, I now realise that this understanding, rather misunderstanding, too, is guilty of gross exaggeration. Recent archaeological evidence from Krimila in Bihar show that new Buddhist monasteries, including the one led by Vijayashree Bhadra, a nun, were being established as late as the end of the 11th century CE, centuries after the alleged demise of Buddhism in India. Critically, Buddhist communities continued to exist in some villages of Patachitra painters from Odisha, there was the Shakya of Uttar Pradesh, the Baruah Buddhists of Bengal and the Himalayan communities stretching from Ladakh to eastern Arunachal Pradesh. Buddhist communities in Tripura link up with those in Bangladesh and onto Myanmar, forming a large Theravada branch that continues into the larger southeast Asia. (These are cited just to bring out the continuity and heterogeneity of India’s Buddhist communities and should not be seen as a comprehensive listing).

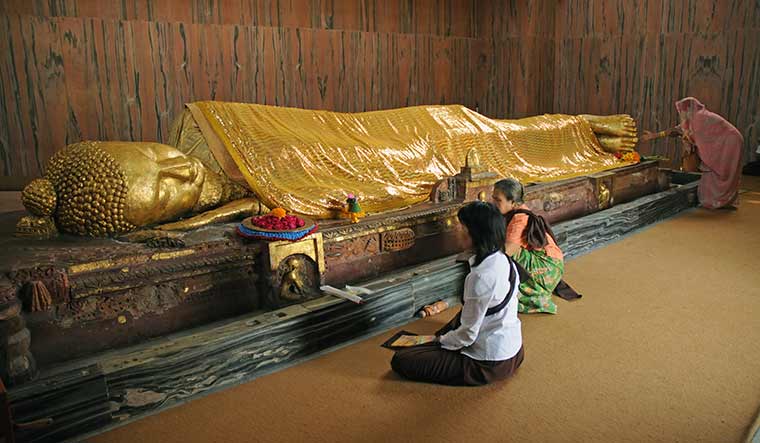

India’s Buddhist heritage, art and architecture, and ethics and values have been deeply entrenched in Indian traditions, so much so that it is well-nigh impossible to separate out diverse strands based on theological origin. Therefore, any talk about the revival of Buddhism in India is to misread history. What is definitely required, and is happening with government support, is to bring focused attention on this heritage and the presentation of its multifaceted manifestations before Indians and the world. What has happened is that we have not been able to project the Buddhist component on India’s heritage in adequate measure, affecting a double loss to both Buddhism and to India. One, that Buddhist sites—there are thousands across the length and breadth of India—are not as well-developed in terms of access, facilities and information. Fortunately, the development of the Devni Mori complex in Gujarat, Aastha Kunj in Delhi and Kushinagar in Uttar Pradesh, for example, show that things are changing. Second, most of the non-Buddhist world do not automatically link Buddhism with India, and do not see it as the land that gave birth to, and sustained Buddhism into becoming the world religion that it is. It is efforts in trying to correct the picture that is very important, and potentially can be misunderstood.

The International Buddhist Confederation (IBC) was set up in 2011 to bring Buddhist communities across the world on one platform. Many predominantly Buddhist countries have national mahasanghas, while many are less structured. There are important monasteries and academies, universities and lay congregations. The IBC has members in 39 countries. In Russia itself, there are members in three of its republics including the republic of Kalmykia, the only Buddhist majority region in Europe. Though funded by the government of India, the IBC is not a government body and, in the years to come, would have to raise resources from diverse sources so that it could potentially act as a successful platform to bring Buddhists across the world together. It is also necessary to dispel some feeling that the government of India is playing the Buddhist card as a strategic instrument In Asia, to counter efforts elsewhere to appropriate Buddhist legacy.

Grand celebrations are organised twice a year. One, during Vesak —Buddha Poornima, which marks Buddha’s birth, enlightenment and Maha Parinirvana. The other is Asadha Poornima, also known as Guru Poornima, which marks the first turning of the wheel of Dhamma, the day that Buddha delivered his first sermon at Sarnath. In addition, IBC and its members organise many local functions, including Dhamma talks for the benefit of believers and non-believers alike.

The IBC also attempts to work with national governments to highlight that country’s Buddhist heritage. An exciting journey to Uzbekistan, where the government has made considerable efforts to restore stupas near the city of Termez, on the borders of Afghanistan, has had to be postponed due to Covid-19 restrictions. Buddhist organisations and media groups from India, Republic of Korea and Japan formed the core of this contact group. There are the ruins of many Buddhist monasteries in the region, and the Kyrgyz Republic and Kazakhstan would be the next countries whose heritage must be better known.

Also read

- India should share its ancient knowledge with the world: The Dalai Lama

- Modi has been working to turn India's Buddhist heritage into strategic asset

- It is tempting to think Buddhism can boost India’s influence in the Indo-Pacific

- What triggered a Hindu-Buddhist dispute in the 19th century in Bodh Gaya

- Abode of peace

- The Buddha trail

India is not just the land of Buddhism historically, but also the centre of Buddhist Studies. Indian universities and academies even today get students in the thousands from foreign countries who come here to study Buddhism. With a view to strengthening academic partnership, the IBC with the support of the ministries of culture, tourism and external affairs (the Indian Council of Cultural Affairs) and the Nava Nalanda Mahavihara are organising a global Buddhist conclave centred on the theme of Buddhism in literature in Nalanda on November 19-20. In order to generate momentum and draw the participation of scholars from across the world, this conclave would be preceded by eight regional conferences including four in India. These would be at Dharamshala, Gangtok, Hyderabad and Sarnath (in India) and at Bangkok, Tokyo, Phnom Penh and Seoul. An academic exchange programme between scholars is also being launched, whereby the IBC would send Indian scholars to universities and academic institutions abroad, and invite foreign scholars to spend time in Indian universities and institutions.

As mentioned earlier, the IBC is also working closely with state governments to develop Buddhist sites, and create appropriate environment in such places for Buddhist organisations globally to set up their presence in these locations.

The effort is clear and it is not political, far from being geostrategic. India does need to project its rich Buddhist heritage, and re-establish itself as the primary centre for Buddhist studies. At the same time, being the home for almost all the holiest places of Buddhism, India must strengthen its partnership with Buddhist organisations across the world. The IBC and its partners do take the help of their respective national governments for facilitation of their work, but these do not go beyond the stated purposes of our institutions.

The last thing strategic thinkers should advocate is for India to play the Buddhist card, for any such approach would necessarily be transactional, and would fail to generate larger goodwill. Far from helping the country gain any strategic advantage, it would possibly result in backlash. India should, instead, strengthen its efforts towards making a large part of the world feel that India is their spiritual home, to which they would travel to renew their beliefs and help make the world a better place.

The author is director general, International Buddhist Confederation, New Delhi.