In 1870, Mayankutty Keyi, a shipping magnate from Kerala’s Malabar region, performed the hajj. The wealthy Mayankutty was not pleased with the facilities provided for Indian pilgrims in Mecca.

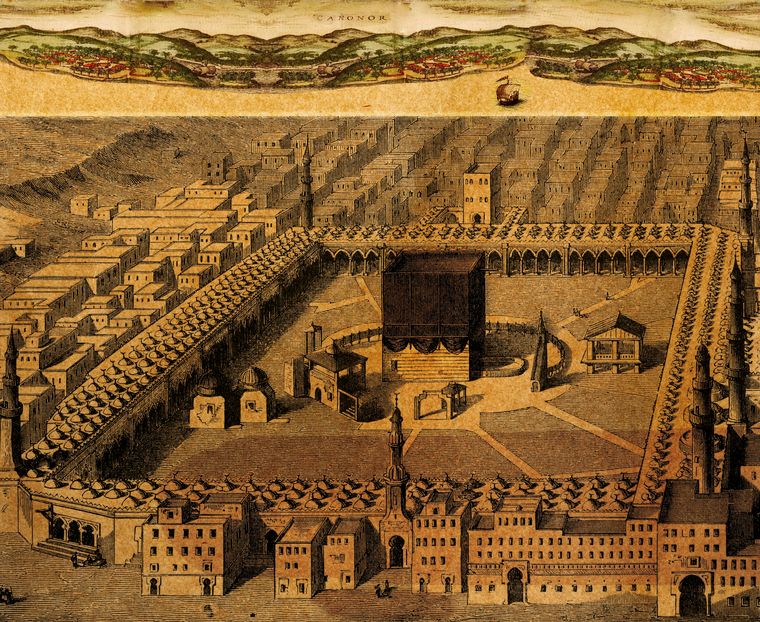

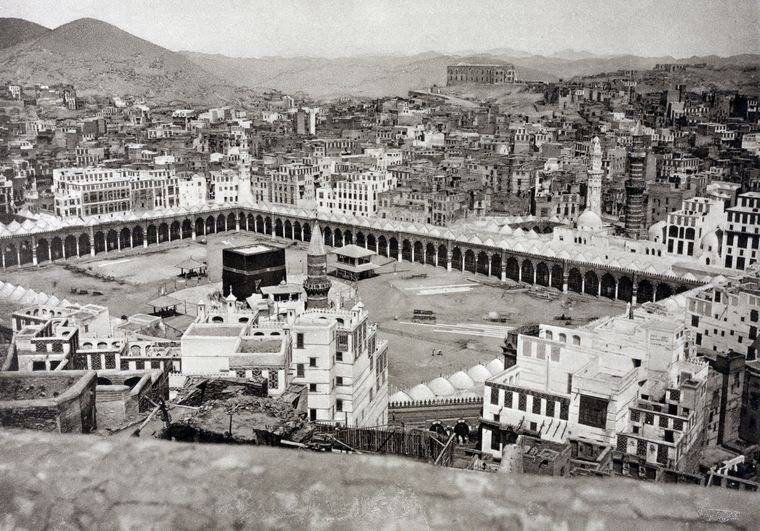

So, he bought 1.5 acres, barely 300m away from the Kaaba—the most sacred site for Muslims—and built a villa there with seven rooms and a huge hall. He named the villa Keyi Rubat, adding the Arabic word for rest house to his surname.

Buying the house was not a big deal for him, as he already had homes and warehouses across the globe—including in Amsterdam and Vienna. Keyi means ship owner in Persian. The Keyi family’s clients included traders of all sizes and even the biggest joint stock company of those times, the English East India Company.

Mayankutty’s father, Abdul Qadir Keyi, was a renowned trader who had hired great scholars to tutor his son. Barely three years before performing his hajj, Mayankutty did something that irked orthodox Muslims in Malabar; he translated the Quran into Arabi Malayalam, the traditional language of the Mappila Muslims of Kerala. He took 15 years to complete the translation, which he thought would make the Quran more accessible to the common man. Enraged puritans tied stones to the translated copies and dumped them in the Arabian Sea. Mayankutty ignored the critics and printed more copies.

Mayankutty married from the Arakkal family. It is the only Muslim royal family in Kerala, and it follows a matrilineal system. The senior-most member, regardless of gender, heads the Arakkal family. Before Mayankutty and his wife left for Mecca, he handed over his business operations to his brother. There are multiple versions of what followed. One is that the couple stayed on in the rubat and never returned. Another is that Mayankutty appointed Moosa Haji Malabari, a Malayali, as his nazir (representative) at the rubat, and returned home.

The fact remains that the rubat continued to host Malabari pilgrims for nearly a century. After the death of the nazir, the wakf department of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia maintained the property.

Around the same time, the Nizam of Hyderabad and the Nawab of Arcot also built rubats near the Kaaba. Later, many nawabs and elite Muslim families built rubats in Mecca, Medina and Jeddah. Being the first mover, the Keyi Rubat had more land than any of them.

The oil boom of the late 1930s transformed Saudi Arabia, and with it the holy cities. In 1956, the Saudi government took over Keyi Rubat’s land as part of a mosque extension project and allotted another plot, a little away from the original site. In 1970, the second plot, too, was acquired for expansion and a generous amount was issued as compensation. As Mayankutty’s legal heir could not be traced, the Saudi government ordered that the money be held in escrow by the treasury of the Awqaf department, which manages wakf affairs, until the heir is found.

THE BIG SEARCH

The Saudi government then launched the hunt for Mayankutty’s legal heirs. It approached the Indian government in 1971; the Indira Gandhi government forwarded the request to Kerala chief minister C. Achutha Menon and asked him to report back.

Like the Arakkals, the Keyis, too, are matrilineal. So, hereditary property is transferred from mother to daughter, or from brother to sisters’ children.

On November 28, 1972, the Thalassery tehsildar issued a certificate of legal heirship to C.V. Aluppy Keyi and C.V. Moidu Keyi, Mayankutty’s great-grand-nephews. The Arakkals challenged the certificate on three reasons: i) The Keyis’ claim that Mayankutty died childless is false; ii) Mayankutty’s children—a son and a daughter—were the legal heirs; iii) Saudi Arabia does not accept the matrilineal system. This challenge triggered a tussle that continues to this day.

FAMILIAL FIRE

Rafi Adiraja, head of the Arakkal Museum in Kannur, has ties to both families. His mother, Adiraja Zainaba Ayisha Beevi, was the 37th queen of the Arakkal dynasty; his father was C.O. Moidu Keyi. “I belong to both the families. Still, I am saying that the Arakkals are the legal heirs of Keyi Rubat, because that is the truth,” he said. Rafi said that the original deed of 1870 showed Mayankutty’s name with the suffix Elaya (the younger)—a title bestowed on him after his marriage to the Arakkal beevi.

Kozhikode-based Harshad Adiraja, a dry-fruits merchant from the Arakkal family, accused the Keyis of fabricating documents to show that Mayankutty died childless. “Mayankutty Elaya’s son, A.P. Ummerkuttty, wrote a book, Keyi History, in 1916. It clearly says that (Mayankutty) had two children—a son and a daughter. We are his heirs.”

The Keyis, however, insist that the Arakkals have only claims and no proof. “We have enough documented proof to nullify their claims,” said P.V. Zainuddeen, a lawyer representing the Keyi family. “The Kerala government had reported back to the Union government in 1972 itself that Mayankutty had no kids, and had chosen his two nephews as the heirs.” Zainuddeen's father is from the Keyi family, but he is not considered a Keyi because of the matrilineal system practised in the family.

FAILED MEDIATIONS

Successive state governments have been trying for a consensus ever since the tussle became public. Similarly, Indian Union Muslim League leaders such as chief minister C.H. Mohammed Koya, Sayed Abdul Rehman Bafakhy Thangal and Union minister E. Ahamed had mediated; the tussle outlived all three.

The first government-level attempt was made by the E.K. Nayanar government in 1998; it appointed P. Kamalkutty IAS to find a solution. “I could not make much headway as there was not much documentary proof available here,” recalled Kamalkutty. “So, I recommended a detailed investigation with the support of the Saudi Arabian government. But nothing much happened after that.”

The matter was followed up by the A.K. Antony government, which took over in May 2001. The government asked state wakf board CEO B.M. Jamal to submit a report. “I studied the matter in detail and even managed to get the original deed of 1870,” said Jamal. “But nothing much could be done as the state government has limitations in dealing with a foreign country. It needed the permission of the Union government to take it forward.”

The matter gathered momentum again in 2013, when the Saudis sounded out the Union government again. Chief minister Oommen Chandy then appointed T.O. Sooraj IAS to follow up. “I had collected all available documents,” Sooraj told THE WEEK. “Going to Saudi was necessary for joining the missing dots, but the state government did not give permission for the travel.”

The matter was taken up by the first Narendra Modi government, too. In 2016, Mukhtar Abbas Naqvi, the then minister of minority affairs, had sought the details of the case. But the tussle remains.

SPECULATORS AND SCHEMERS

There is no end to speculation about how big the amount with the Awqaf treasury is. In 1971, according to official documents, 1.4 million Saudi riyals had been deposited. Many international media reports value this at $1 billion (approximately Rs7,500 crore) today.

Sooraj admitted that there is no clarity about the amount. “There is no interest [system] in Saudi Arabia, but what is not clear is whether the amount will be adjusted for inflation since 1972,” he said. “There had also been talks that the money was invested in the land bank there. In either case, the amount would be humongous.”

The controversies have brought lots of attention—good and bad—to both families. According to Zainudeen, some international agents and middlemen have approached the family with some deals for lobbying. “The amount they promise is so huge that people will go crazy,” he said.

“There are a lot of conspiracies and vested interests in play. The money involved is that huge,” said a Keyi, who requested anonymity.

Rafi, however, said that since the rubat was taken away without due process, the Saudi were willing to meet any demand of the legal heirs. “The amount is what we ask for.... It can go anywhere up to Rs1 lakh crore,” he said.

Harshad said that he shudders at times “thinking of the amount his family is owed”. “We may or may not get it. But it does give a sense of satisfaction—may be a false one—that a huge amount is awaiting us in Saudi Arabia,” he said.

WAKF PROPERTY OR NOT?

Interestingly, there is a third claimant to Keyi Rubat—God, through wakf. Wakf property is a permanent dedication of any movable or immovable property by a Muslim, for a cause which is pious or charitable according to the shariah. A section of the Keyis insist that Keyi Rubat belonged to God. “It was certainly a wakf property dedicated to Allah. How can anyone even think of taking it home?” said Zainuddeen.

His view was corroborated by Jamal. “The wakf would be a continuing entity. A person creating the wakf cannot take back the property,” he said. “All that the legal heir can decide is the muthavally (manager) to look after it.” According to him, the Saudis may allow the legal heirs to bring the money to India. “But that money can be used only for religious purposes,” he said. He added that the state wakf board has requested the Central wakf board to re-establish Keyi Rubat as a rest house for hajj pilgrims from Kerala.

But Rafi says there is no evidence that the rubat was a wakf property. “Keyi Rubat was certainly a rest house for pilgrims, but that does not make it a wakf property,” he said. He pointed out that the legal heirs of the other three Indian rubats were compensated by the Saudis.

Rafi also said that Saudi Arabia, being a rich country, does not need the money. “They do not need our money, while our country needs it badly. We want to build something meaningful with the money to reinforce the secular culture of our land,” he said.

A Keyi, who wished to remain anonymous, told THE WEEK that he did not understand why some family members were insisting that it was wakf property. “Who will say no to such an amount?” he asked. According to him, many Keyis are no longer as rich and powerful as they used to be. “We would be grateful if we get at least a small share of the family fortune,” he said.

When asked about the delay in producing the legal proof, which both families claim to have, Zainudeen said there are hundreds of family members to be traced and established. “It will take some time,” he said.

Rafi, on his part, said he had set all the records correctly and would be making the “right moves” soon.

Both the families are meanwhile planning to take up the matter with the state and the Union governments again. Thalassery MLA A.N. Shamseer said that the Pinarayi Vijayan government would do its best to settle the matter amicably. “We all are proud of Mayankutty’s contributions. The need of the hour is to find his legal heir,” he said.

SAUDI’S PREROGATIVE

Despite these claims and counterclaims, the ball is in the Saudis’ court. “The last word, certainly, is that of the Saudi government,” said Jamal. “If anyone from the two families could stake their claim with evidence, then they will be accepted as the legal heir by the Saudi government.”

According to Kannur City Heritage Foundation director Muhammed Shihad, any proof should match Saudi records. “Only the Saudis have the [original] documents. The day someone can provide matching proof, the matter is settled,” he said.

Culture connection

The culture of north Kerala, especially that of the Muslim community, is a mix of Arab and Kerala traditions, thanks to long-standing trade links between Arabia and the Malabar coast. The sea trade to India was almost entirely controlled by Arabs, until the Portuguese landed. Many Arabs settled in Malabar and married into local families, cementing the blend of cultures. The origin of Arabi Malayalam is one striking example of this cultural blending.

The Keyis

The Keyis of Thalassery were wealthy traders and reportedly owned properties in all major ports in India, and some in Europe, too.

The Keyis started trading in the 17th century, when the French East India Company established a factory at Thalassery. Aluppy and Moosa were the pioneers. Their successor, Kunhipacki Keyi, who became the head of the family in 1809, was the first one to receive the honorific keyi (ship owner). He had a large number of sea-going vessels; reportedly, 650 at one point.

His nephew Moosakakka Keyi took the business to greater heights. When Tipu Sultan invaded north Malabar, he hid the Chirakkal Hindu royal family and then provided the Chirakkal raja with safe passage to Travancore. Tipu’s invasion hit the Keyis badly and it was the king of Venad who helped them rebuild their business.

The Arakkal royals

There are many stories about the founding of the Arakkal family, Kerala’s sole Muslim royals. A popular legend is that a princess from the Chirakkal Hindu royal family was saved by an Arakkal man from death by drowning. He gave her a dhoti after pulling her out of the river. The princess insisted that she was given a pudava—a Hindu marriage ritual—and that she would prefer to live with the man who first performed the rite.

The Chirakkal Raja, though not happy initially, accepted his daughter’s choice, granted her property and a palatial home. It is generally believed that the matrilineal system followed by them began with this princess and her inter-religious marriage.

In the Arakkal family, the senior-most family member becomes the head—regardless of gender. If the titular head is a female, then she will be called Arakkal beevi. The beevi’s husband’s name is suffixed with the title Elaya, to denote that he is the royal consort. That is how Mayankutty Keyi became Mayankutty Elaya. Historically, the Arakkal royals and Keyis have had strong ties through marriage.

Finding the rightful heir is key

V. Muraleedharan, minister of state for external affairs, told THE WEEK that the Union government will do everything possible to solve the Arakkal-Keyi dispute. “It has been going on for quite some time and needs to be sorted out,” he said. He said that the only official communication that the Indian government has received is a letter from the Saudi Arabian government requesting assistance to trace the legal heir of Keyi Rubat. “Being a native of Kannur, I have heard lots of stories about this rubat since my childhood,” he said. “The solution lies in finding the rightful heir, and that needs to be done.”

When Aurangzeb’s army took on the English East India Company in the Anglo-Mughal War (1686-1690)—the first Anglo-Indian war on the Indian subcontinent—the Arakkal royals sent their warships to support him. The company was humiliated in this war.

The Keyis were keen sportsmen. Cricketers such as C.P. Poker Keyi and Kunhipackey ‘Sixer’ Keyi had played against English teams, as Kannur was a cantonment for the Portuguese, the Dutch and the British. The family is also credited with popularising tennis in Thalassery, Kannur.

According to legend, Mumbai’s Malabar Hill, now an elite residential area, once belonged to the Keyis, who are Malabari Muslims. The port city would have been a natural base for this shipping family.

In the Arakkal family, the senior-most family member becomes the head—regardless of gender. Among the 39 titular Arakkal heads, 13 were women. Junumabi, the 23rd ruler, reigned for 42 years, and Aishabi, the 25th, ruled for 24 years.