A round 9pm on April 25, 2020, Dr Balram Bhargava received an SOS call. Dr Manmath Das, a retina surgeon from a hospital in Bhubaneswar, was calling in for advice on a peculiar case. Bhargava, director general of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) was all ears.

A 30-year-old diabetic with complete loss of vision in the right eye had arrived at Das’s hospital, travelling 120km. For a year, he had been using his left eye without much trouble, but that particular day he sensed a sudden drop in vision in the left eye, too.

Das knew that the man had to be operated upon the next morning, or he could lose his remaining vision. But he was apprehensive as he did not know the patient’s Covid-19 status, and with the limited testing available then and the time it would take for the report to come, it would be too late. Many cautioned him against doing the surgery, as he stood the risk of getting infected and passing it on to his two small children and aged parents at home. But Das’s conscience did not let him rest; he knew that the surgery could give the young man a new lease of life. Time was running out and a decision had to be made quickly.

Bhargava immediately checked the case load of the block from where the patient hailed. It was a green zone, meaning there were zero Covid-19 cases. He then asked if the patient’s family members or the vehicle driver had any symptoms; none, said Das. Bhargava needed no further information. He asked the surgeon to take all possible precautions, for himself and the patient, and to go ahead with the surgery. The operation was a success and the patient’s vision in the left eye returned to normal.

As the pandemic ravaged the country, such were the emotionally charged moments of desperation and despair that called for the ICMR director general’s direct advice and intervention— sometimes even at 3am. Before March 2020, Bhargava had never slept with his phone next to him; he was not on WhatsApp either. The pandemic changed all that. “Every other person turned into a spammer with unsolicited advice on tackling the virus. I had to really fight to make a point,” he says.

While the ICMR emerged as the frontal agency tackling Covid-19 in India, Bhargava became its go-to person. In his career spanning three decades, Bhargava, a cardiologist by qualification and professor at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, has served as physician to some of the most high-profile state dignitaries, including past vice presidents and the prime minister. Thanks to Covid-19, he found himself learning the ropes of public health and virology, alongside media and public relations and crisis management. His mantra was simple: “Dip into solid science, stay calm and carry on.”

Bhargava is the 12th director general of the 110-year old ICMR (formerly Indian Research Fund Association). While he took charge of ICMR only in 2018, his first brush with the institute was when he was barely four. It was early 1960s, and ICMR’s first director general, Dr C.G. Pandit (1948-1964), had visited King George’s Medical College (KGMC) in Lucknow, and met Bhargava’s father, Prof Krishna Prasad Bhargava—a physician, professor of pharmacology and later principal of KGMC. The young boy, “curious and studious by nature”, grew up on the KGMC campus. He spent 30 years of his life there, studying medicine and specialising in cardiology. “Whatever I am today, it is thanks to my life spent in Lucknow,” says the 60-year-old Bhargava.

On a November morning, we are seated inside his spacious office at the ICMR headquarters in New Delhi. The entire facility looks clean and is adorned with flowering plants. His office, too, has plenty of potted plants. That, he says, is the first change he brought about after taking over as director general. “The second one was cleanliness,” he says. “And, the third was to bring in a culture of accountability.”

His colleagues from the 28 institutes that fall under the apex body refer to him as “one-of-a-kind taskmaster who has shaken up, corporatised and energised the research institute”. They add, “When Dr Bhargava is asked about the deadline of a project, his immediate reply is, ‘Oh! that was yesterday.’”

Bhargava laughs, before agreeing, “Yes, it is true and it was important to make them realise that they have limited time to do things… to complete their projects. Many projects were on extension and they were requested to stick to timelines. My instructions have been very clear from the start, that we will not do armchair research in an ivory tower just for the sake of it. It has to be translational, which means it has to add value to people and must be solution-driven.” He has published 250 research papers over 30 years, most of which are translational. “We are a nation in a hurry. We should aim for the ICMR to be top class in the world,” he says.

A taskmaster he is, but a soft-spoken one at that. Despite being seated barely a few metres from him, one has to lean in to catch his words.

On a table nearby is a stack of his recently published book—Going Viral—which is based on the making of Covaxin and carries a foreword by the Dalai Lama. “The main reason this book has been written was to talk about the advancement of science and research in India and as a tribute to scientists,” he says. “The science and research institutions of India need to be nurtured and promoted in a big way. For example, since 2018, the budget of the ICMR has doubled and we do not need to be fully dependent on foreign funds for research. We must do tertiary research that is relevant for India, rather than being part of some foreign study. What you see at present is Version 2.0.”

His colleagues and scientists working under him agree. Dr Pragya Yadav, a scientist from ICMR-National Institute of Virology, which played a key role in the fight against Covid-19, narrates an anecdote from September 2018 when Asiatic lions in Gujarat were infected with an epizootic infection caused by the canine distemper virus. The team, led by Bhargava, had detected the virus in samples from 68 lions and 6 leopards by RT-PCR.

“He aggressively pursued the study, made it public, followed up for vaccines for the cubs and took initiatives for their conservation,” says Yadav. “That was the first time we saw a director general being so serious about our research. This sort of decision-making and quick turnaround time has never been seen in the ICMR before. We used to do our work in the shadows with no one to question and no one to notice.” She has served under four director generals till date.

Another colleague who works at an ICMR institute points to Bhargava’s prompt action during the Nipah outbreak in Kerala in 2018. “Generally, what happens is that if there is an outbreak, people follow a protocol that goes through assessment of the disease, reporting, management, but Balram sir aggressively chased the virus,” she recalls. “He called for the monoclonals and developed clinical trial protocols. He got a team deputed to Kerala within 24 hours. His quick thinking got us prepared in time.”

This ability to think on his feet and get things done shone in Bhargava early on. While practising at KGMC in the late 1980s, he came across an 85-year-old patient who had slipped into a coma; she remained in that state for two days. Scans and blood tests were done, but they did not reveal the cause.

At the time, new machines to measure sodium and potassium levels had been installed at the medical college. During the night, Bhargava, out of the blue, measured her sodium levels. He found it to be extremely low—94mEq/L; the normal level is 130 plus. However, his team had no access to sodium. All they had was normal saline, which is 0.9 per cent saline, meaning it has only 0.9g of salt in 100ml of solution.

At 2am, he and his colleagues went hunting for sodium. They found a 4.5 per cent sterile sodium solution at an emergency chemist, which was then used for inducing abortion. They took it, diluted it and administered it to the patient, who woke up in a couple of hours.

“The point is to enjoy the process. I am completely in love with what I do, especially as a doctor and clinician,” he says. “And the credit for that goes to my teachers who shaped me and led me towards this path.”

His eyes well up. As he reminisces about his biology teacher G.R. Sahni, who taught him from Class 8 at the Colvin Taluqdars’ College in Lucknow, his voice wavers and becomes even more softer. “I may get emotional as I remember my past, so pardon me,” he says. “He was the one who made me fall in love with botany and biology. That is how I fell in love with medicine. I owe him my career and my life.”

He pauses for a bit before adding, “I also had excellent teachers who taught us English and Hindi literature.” As if on an impulse, he begins reciting verses by renowned Hindi poet and writer Bihari Lal, followed by Kabir’s famous couplets. And, just like that, the mood in the room changes. There is a lilt in his voice, a spark in his eyes and his face lights up as he snaps his fingers to the rhythm of his verse. “All this and more we learnt in school. Can you believe it?” he asks. “I know it all by heart.”

Sahni remembers him as a “brilliant student who was exceptionally gifted, both in academics as well as in debates”. He taught Bhargava till class 12, before moving out on deputation to the ministry of external affairs to teach students of Indian domicile in southeast Asia. “When he was awarded the Padma Shri, he called me and came over to meet,” recalls Sahni. “He introduced me to his colleagues as his most adorable teacher. I felt really honoured.”

But his connect with cardiology began with a heart-breaking incident—his father suffered a heart attack while he was a visiting professor in Canada; Bhargava was just 15 then. In a way, thanks to his father, he dived into research, too. In later years, his father took to chewing tobacco, which would upset Bhargava. He went on to write a seminal paper on the effects of chewing tobacco on the arteries. He even made a patient chew tobacco while performing an angiogram to prove that it constricted the arteries and led to clot formation.

It is 2pm, and we break for lunch. But Bhargava need not step out; he carries his lunch with him—two rotis and sabzi rolled and wrapped in an aluminium foil. “It is quick and I look forward to a surprise roll every day,” he says.

The youngest of four siblings—two sisters and two brothers—Bhargava was the most pampered one at home, says Dr Rani Bhargava, his eldest sister. Eleven years older to Bhargava, Rani is a general physician in Ahmedabad. His younger sister, who did her bachelor’s in education, and his elder brother, who runs an advertising firm, live in Delhi. “Ours was a very cultured, disciplined and fun childhood,” says Rani. “Our mother, being a graduate of music from Bhatkhande Music College, Lucknow, with a master’s in Sanskrit, taught us to appreciate the arts. We were also very well-travelled, thanks to our father’s frequent fellowships and postings as a professor in different countries. But each time, we would go as a unit. He never travelled solo.” Bhargava’s favourite city is St Petersburg, Russia.

The passion for medicine continues in the next generation, too; Bhargava’s sons, Raghav and Madhav, are both doctors. While Raghav is an endocrinologist in the UK, Madhav has specialised in general medicine and is at AIIMS now. The three doctors have been involved in the fight against Covid-19 in their respective capacities. When times were tough, they would brainstorm on how to better testing and treatment, and Bhargava would present those suggestions to the committees.

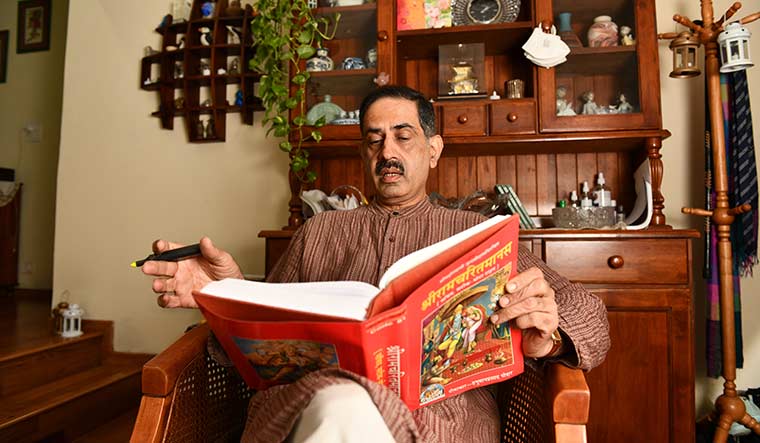

It is a languorous Saturday afternoon and there is a nip in the air when we arrive at Bhargava’s AIIMS quarters, inside the lush green neighbourhood of Asian Games village in south Delhi. His wife, Sunita, and younger daughter-in-law, Swati, are at home, so is Rani, who is recovering from an eye surgery. Each woman has a story to tell about Bhargava.

“All four of us have grown into well-rounded individuals as we were exposed to the world,” says Rani. “My little brother is domestic and professional in equal parts. A vegetarian, he knows how to cook sumptuous Uttar Pradesh fare.” Agrees Swati, who swears by his famous mixed grill platter that he serves with wine. “That is something the whole family waits for,” she says. Add to that some great conversation. “Papa can talk about everything under the sun, from carpets to carpentry, travel to wildlife,” says Swati, who works with the Atal Innovation Mission at NITI Aayog.

But it is his wife who spills the tea. “His idea of relaxation at home is to get things done… repair broken stuff, clean things... but never to sit idle,” she says, exasperatedly. “When you are not prompt and delay stuff, it angers him. In that sense, we are total opposites. I am laid-back, while he is always on the move.”

One thing all three women agree on is that he is “very helpful”, especially when it comes to finding somebody a job or getting someone an admission or finding a bed or doctor.

The ICMR director general is also a man of quirks—he enjoys James Bond movies, but only in theatres; he has a collection of Beatles records; he can devour green chillies and ginger—any amount and in any form; he can slip into a deep slumber anytime.

During our meeting at his office the previous day, Bhargava had shared something interesting. According to him, the two aspects that signify “the luxuries of life” are: a fireplace at one’s home and being connected to nature. When we meet at his house, he takes me to a balcony that is brimming with a variety of plants; and then to a small, makeshift fireplace in his living room that runs on biofuel, which, he says, he made on his own. “This is luxury for me,” he says, grinning his widest grin of the day.

Bhargava admits that he is one of those rare doctors who muster enough courage to operate on one’s family or are willing to be operated upon by their students. “I have faith in my students and I was sure I wanted them to place a stent in me,” he says.

What is that one thing that he dislikes about himself? “I feel I can improve on my communication skills and be more patient,” he says.

In 2019, Bhargava won the Dr Lee Jong-wook Memorial Prize for Public Health for his achievements as a clinician, innovator, researcher and trainer. Innovation holds a special place in his heart, especially cost-effective, frugal innovation. More than a decade ago, when the cost of stents had grown sharply in the country, he asked his brother-in-law, Anil, a jeweller in Bombay, to make a stent out of platinum iridium because that was the most biologically accepted metal.

“So, he made it and we studied the impact of that stent on animal models and demonstrated that those work better than many other commercially available ones prevalent at the time, mainly made of stainless steel,” he recalls. “I realised that we have to constantly innovate in our own country and develop our own medical devices because 80 per cent of the medical devices are imported.” It was at that time that he helped launch the Stanford-India Biodesign Programme to train young Indian innovators.

In the area of medicine, too, he introduced India to alcohol septal ablation (ASA) in 1995. He saw its application in London during a training programme. ASA is a non-surgical procedure to treat hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (the abnormal thickening of heart muscles) by injecting one’s heart muscle with alcohol. The alcohol is toxic and causes some of the heart muscle cells to shrink and die. This improves blood flow through the heart and to the body. “There were discussions about this technique, as it had never been tested in the world,” he says. “We did it and the patient recovered fully. Ultimately, ASA became an established technique, which was later adopted by many western nations.”

Though a medicine man through and through, there was a time when he “almost believed in miracles”. He cites the case of a former Union secretary who collapsed while playing tennis. Bhargava asked that the patient to be brought to the emergency unit at AIIMS. Bhargava gave him a cardiac massage, but he did not respond initially.

“We already had him on the ventilator and then we rushed him to the cath lab,” he recalls. “One of his main arteries was blocked. We opened that up. He recovered, but was on the ventilator for three to four days. After that, he caught ventilator-associated pneumonia. He recovered from that, too, and was then discharged.”

Six months later, the stent that had been put in got blocked. An angiogram was performed again and he was sent in for a bypass surgery. “He went for a bypass surgery and recovered,” he says. “After that, he oversaw the marriage of two of his children, and he is still fine. It is fascinating that an individual continues to live by way of his willpower despite the body going through so much.”

A typical day in the life of the ICMR chief involves back-to-back meetings with the health ministry and numerous secretaries of government of India.

Did he ever consider making a shift to the private sector or taking up a position abroad, especially since his specialisation in interventional cardiology is a lucrative field? “I was lured many times, but my elder brother advised me and helped me financially, whenever it was needed,” he says. “Being at AIIMS has allowed me to do research, teach and help patients.”

He says he had the opportunity to stay back in Washington and later in Glasgow, both places where he had been for training. But he chose to return as he “wanted to make a difference here” rather than being just another one lost in the mill there.

Decision-making, he says, is the most challenging part of his job, especially so during the pandemic. “We were going crazy,” he confesses. “Right from the drugs to be introduced in the market to the innumerable treatments people came up with for Covid-19 to the reasoning with the task force on multiple aspects, it was all happening simultaneously and anything could go wrong anytime. But in the end, we all worked as a team and the government extended its full support.”

Moreover, there were critics and the media to answer to. Bhargava’s book has been criticised in certain quarters for “showing the government in very good light”. “Not at all,” he says. “I want to put it on record that the government has been extremely cooperative and encouraging. It did lean on science, which was fantastic.”

Does he think Covaxin did not get approval as easily as other vaccines, especially Covishield? “Yes, that is true,” he says. “Perhaps, had it been called any other international biotech, it would have done well. Such is our mindset.”

If there is one thing he could undo in the way the ICMR handled the pandemic, it would be the way they communicated, he says. “We will communicate better. We have no regrets because we scientifically published everything and documented everything systematically,” he says. “I think initially we were slightly isolated as an organisation and could have been more seamlessly woven into the entire scientific work narrative.”

And, did he feel like hanging up his boots in the past two years? “Many times,” he says, with a sigh.