When not only partition but also carnage accompanied India’s independence in 1947, Winston Churchill, who had never concealed his dislike of the freedom movement, claimed that anarchy would be free India’s fate. “The future,” he prophesied in September 1947, “will witness a vast abridgment of India’s population.”

There were other doomsayers, too. All proved wrong by India’s post-1947 stability, not to speak of population growth. Who wrought our nation’s stability? Who caused the Indian nation-state to grow? As with a family, perhaps a nation’s true builders are those who do not beat their own drum, those who may not even want anyone to know about them.

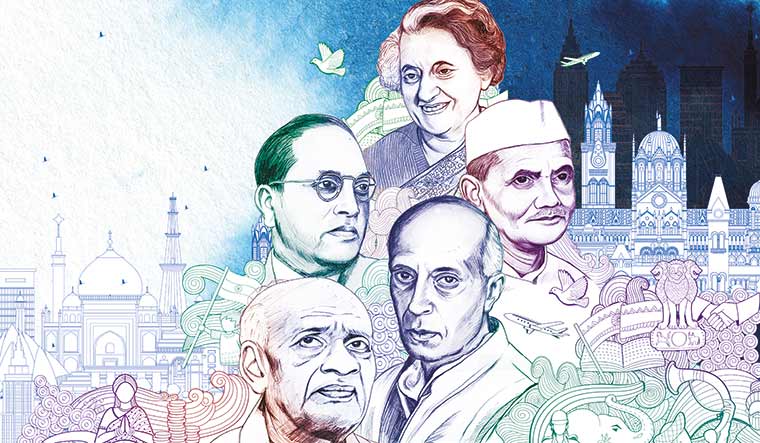

All the same, we know that India’s stability was initiated by Jawaharlal Nehru and Vallabhbhai Patel, who together led free India’s first government. In fact, the tide turned on January 30, 1948, when Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated. Indians had bonded with Gandhi from 1915 onwards. In Tagore’s words, “As soon as true love stood at India’s door, it flew open.” Within months of the 1947 carnage, hate took Gandhi’s life too. Shock and grief produced a recognition of reality: Indians had to set aside their enmities and live like brothers.

In 1949, piloted by B.R. Ambedkar, the Constituent Assembly turned this recognition into articles of the Constitution and solemn oaths of liberty, equality and fraternity. Someone born an ‘untouchable’ drew up the rulebook for a society that had condoned oppression for centuries. Hundreds of ‘high-caste’ legislators joined him in this project for equality, which was also a project for order.

The Constitution was a proud feat of history. Though amended dozens of times since, and not always wisely, it has remained a shield for democracy in perilous times, albeit a shield that only protects when judges and the media hold it high. Ambedkar’s role goes beyond the Constitution. His biting, unrelenting and profound critique of Indian society, and his public conversion to Buddhism shortly before his death in 1956, endure as reminders that traditions, situations and claims require frank scrutiny.

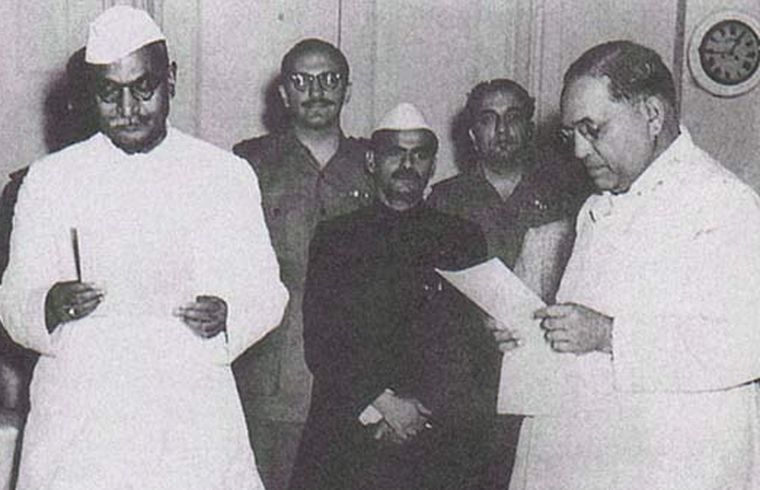

Patel was not yet 72 when in August 1947 he became the nation’s deputy prime minister, home minister, minister for information and broadcasting, and minister for the princely states. In 1947, however, 72 seemed quite a senior age. Moreover, years of struggle and imprisonment had damaged Patel’s body, and the Gandhi assassination produced a heart attack that curbed his exertions for months. In December 1950 he died. Well before his death, however, he had accomplished a remarkable exercise: Getting hundreds of large and small princely states to merge into the Indian Union.

His was not a solo feat, just as Ambedkar did not make the Constitution all by himself. In V.P. Menon, Patel had a sharp and seasoned officer who not only converted the verbal assent that Patel had secured from princes into binding legal documents where necessary but also obtained verbal assent himself. Another valuable Patel ally in getting the maharajas to fall in line was the last viceroy, Lord Louis Mountbatten, who was related to the English royals. Invited by Nehru and Patel to continue as governor-general, Mountbatten candidly told an assembly of rajas on July 26, 1947, that accession was in everyone’s interest.

Nehru with his anti-feudal aura was a third ally at times invoked by Patel. “If you don’t like my terms, would you like to settle with Pandit Nehru?” Patel only had to hint at the question, which was lodged in the rajas’ nervous minds from the start.

Others supported Patel, but he played the chief role. Another Patel accomplishment is less widely known but was almost as critical. Thousands of civil and police officers who until freedom were part of the Raj’s machinery for India’s governance had to work under new ministers in New Delhi and in the provincial capitals. For their involvement in Quit India in 1942, or in earlier struggles, many of these new ministers had been jailed for long and hard spells by officers now ‘under’ them. Possessing a unique influence in the Congress party, Patel also quickly won the confidence of the party’s recent antagonists, the officers. Trusted by both sides, he provided an essential bridge for India’s post-independence journey.

Loved by the masses and also by intellectual India, Nehru will live in history not because he was prime minister for 17 years, or because his writing and speaking skills were considerable, which they indeed were. At least two of his speeches, ‘Tryst with Destiny’ and ‘The Light has Gone Out’, are unlikely to be forgotten. Nehru lives in India’s story for a bigger reason: He strengthened the institutions on which a nation’s democracy rests.

Soon after India’s independence, many nations in Asia or Africa also got rid of colonial masters. Most of them farewelled democracy, too. India remained democratic because its legislature, judges, officers and media retained their independence. Many factors and people lay behind this achievement, which would have been impossible but for Nehru’s ceaseless efforts to keep our legislature, judiciary, services and media in decent health.

It may be true that Nehru, immensely popular until China’s success in the 1962 war, could have become a dictator had he wanted to. But that question may not be as important as it seems. Other leaders, too, were uninterested in becoming dictators, yet they might not have made the conscious work that Nehru put in, week by week and year by year, to instil strength into vital institutions.

This sweat by Nehru used to be well-known. His respect for Parliament, for our federal polity, for opposition MPs, for the courts, for a free press, his fortnightly letters to chief ministers, his enjoyment of cartoons lampooning him—until 2014 all this was frequently recalled. He merited criticism too, of course, and some of his failures were pretty serious.

Inevitably, Nehru made many political enemies. The significance of his contribution to India’s democracy was, however, captured in a remark that C. Rajagopalachari made when Nehru died in May 1964. Perhaps Nehru’s sharpest adversary at that time, Rajaji said: “A beloved friend is gone, the most civilised person among us all.”

Eight years before Nehru’s death, the redrawing in 1956 of India’s provincial or state boundaries to align them with linguistic frontiers—the so-called Linguistic Reorganisation of India—had made democracy more tangible to the common Indian. Though partition memories discouraged tampering with boundaries, and Nehru personally was disinclined to change existing lines, governance in the language of the people made clear sense. Nehru submitted to the democratic urge.

In his short premiership from June 1964 until his death in January 1966, Lal Bahadur Shastri made two bold moves. One of them, disliked by most politicians in north India, was to yield to the south’s opposition to imposing Hindi as the country’s official language. In thus yielding, Shastri helped preserve India’s unity. His second move, coinciding with a Moscow-sponsored Indo-Pak summit in Tashkent in the aftermath of the 1965 war, was to attempt a long-term reconciliation with Pakistan. Shastri’s sudden death in Tashkent put paid to this brave aspiration. In the years that followed, South Asia saw blindness, fresh wars in 1971 and 1999, and the construction of the nuclear bomb.

In 1971, follies by the generals who ran Pakistan, but refused to see the resentment building up in that nation’s eastern wing, revealed to the world the steel inside an Uttar Pradesh-born Kashmiri woman. Colliding with that steel two years earlier, Indian politicians had provoked Indira Gandhi into becoming a formidable leader. The emergence of Bangladesh, to which she and the Indian Army had made a solid contribution, did not quite lead to the kind of harmony in the strategic northeast India-Bangladesh region which some had expected, but the Indira Gandhi image was elevated.

In our land and beyond, people called her an image of Mother India. Some political opponents went farther and called her a goddess. Yet no one, it appears, is immune from history’s ups and downs. In the Emergency-linked fall in her stature, Indira was joined by many, including, notably and sadly, many judges, editors and newspaper publishers. There were memorable exceptions, such as the risk-taking Ramnath Goenka, who owned The Indian Express. Democracy was also defended across India by small journals.

In the judiciary, there was Justice Hans Raj Khanna, who revived something of the wounded Constitution’s spirit by dissenting from the Supreme Court’s lamentable 4-1 decision to accept the government’s claim that in an Emergency even the rights to life and liberty may be abrogated. As he knew he would be, Justice Khanna was superseded when the time soon came for a new chief justice to be appointed. Resigning, he earned a place in history. The examples of Khanna and Goenka, and others who revealed a similar spirit, tell us that a proper look at the post-1947 evolution of the judiciary and the media, though beyond the scope of this article, has to be part of our understanding of India’s journey.

Here it should suffice to say that contrasting traits—timidity and courage, conformism and independence—were demonstrated in both institutions. It might be added that throughout the post-1947 period a galaxy of satirists and cartoonists, many of them from southern India, people like K. Shankar Pillai, Abu Abraham, R.K. Laxman and O.V. Vijayan, to name a few, preserved the right to make fun of the mighty.

Forty-five years after freedom, in 1992, India became more democratic at ground level when the 73rd amendment to the Constitution authorised elected local councils to govern villages, blocks of villages and districts. Mandated reservation for scheduled castes, scheduled tribes and women in these Panchayati Raj councils (at all three tiers) has brought a measure of equity to the Indian soil. By reserving seats for women, the Panchayati Raj legislation pioneered a reform that has yet to reach state and national legislatures.

Another reforming measure that brought India closer to the world’s higher-ranked democracies was the 2005 Right to Information Act. In practice, the panchayat councils seem to have worked better than this RTI provision, which New Delhi and state capitals have frequently flouted by claiming, usually without justification, that providing the information asked for would jeopardise national security.

Even a quick look at the trajectory of post-1947 India must acknowledge the roles of two groups that may appear to be very different or even opposed: pioneers of information technology and other innovators in business and industry on the one hand, and, on the other, defenders of the rights of the marginalised, of our vanishing forests, of our right to breathe, our right to speak out, to protest.

The strategy of mobilising some Indians against other Indians has always been politically appealing. Before 1947, the Muslim League employed it successfully, and Pakistan was created. After 1947, caste-based or community-based parties often progressed by highlighting perceived discrimination.

From the late 1980s onwards, India’s most successful political mobilisation was achieved by openly or indirectly portraying India’s Muslims as an unpatriotic community and certain political parties as that community’s appeasers. In this strategy of communal ‘othering’, Christians have at times been joined to Muslims. At other times, India’s Christians are invited to join in ‘othering’ Muslims.

A political scientist looking at the last three or four decades of all-India politics (from which state-level politics may at times significantly differ) would say that the strategy of ‘othering’ Muslims (and Christians) trumped alternative strategies of ‘othering’ the Hindu high castes. The former strategy’s success was seen in the BJP’s emergence in the 2014 elections as India’s largest political force and in the rise of Narendra Modi. Both outcomes were re-emphasised in the voting five years later.

In democracies, political victories are notoriously impermanent. Still, the last three decades have shown that majority victimhood can at times be a profitable card to play. The world and India have also found, however, that ‘othering’ a section of the population has injurious consequences. One of those consequences is that democracy’s institutions are damaged or even destroyed. Another harrowing result is that many in different corners of our land, including the old, the disabled, the weak and the helpless, may face bullying, attacks and even death at the hands of aggressive super-patriots.

As the hallowed Preamble to our Constitution reminds us, “We, the people of India” promised ourselves and our compatriots “justice, social, economic and political; liberty of thought, expression, belief, faith and worship; equality of status and of opportunity; and to promote among them all fraternity assuring the dignity of the individual and the unity and integrity of the nation”.

And Article 14 of the Constitution lays down that “The State shall not deny to any person equality before the law or the equal protection of the laws.”

Any ideology that holds that because of their religion, caste or language some in our land are ‘authentic’ Indians while some others are not is clearly unconstitutional. Such an attitude also takes an axe to democracy, to India’s unity, to India’s relations with the world, and to the vision—which is also the Indian vision—of all of humanity as a single family.

How India will find strategies of partnering, not othering, of including, not excluding, of presenting to the world an India of a united and equal people, is not for an observer of India’s journey to suggest. Yet that may be the demand of our times.

Rajmohan Gandhi is a historian.