The virtual world looks much like the real world now. There are gardens, streets, art galleries, cafes, skyscrapers and dog parks in a 3D system. In addition, the entire system is decentralised; you can vote (which will carry a weight proportional to your investment) on the rules that will govern your world. Four years ago, parcels of land in the city were sold for as low as $17. By 2021, the prices were in six figures. Welcome to the ‘metaverse’ of Decentraland, available on the Ethereum blockchain.

Have you ever fancied collecting era-defining artworks, a Monet or a Pollock? Now, for as little as $1, you can earn fractional ownership of highly sought-after digital artworks like the legendary Shiba Inu ‘doge’ meme (valued at around $175 million), or the modern absurdist pieces like ‘The Last Shawarma’ (valuation of six figures), which recreates ‘The Last Supper’ with characters from Marvel’s Avengers series.

All of these are just the tip of the iceberg. There is a digital assets revolution going on—from decentralised finance (DeFi) to non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and the evolving concept of the metaverse—and its proponents say it will remake the world as we know it.

The anatomy of cryptocurrencies

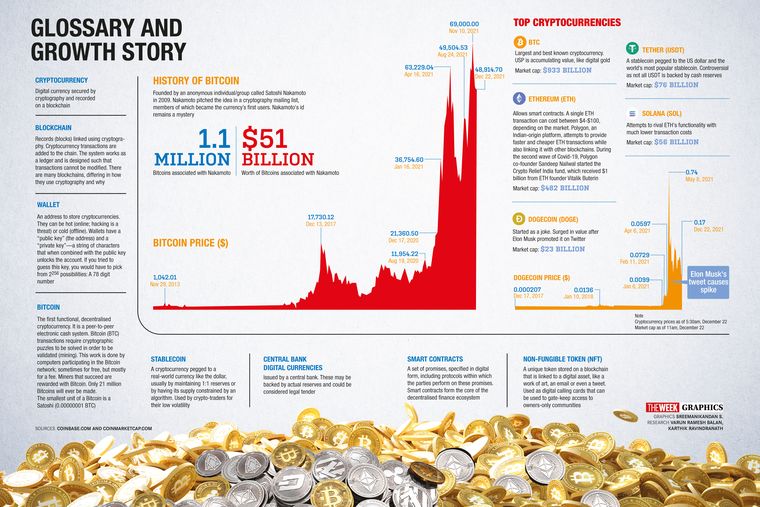

It all started in October 2008, with the release of the first cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, which was 3,000 lines of C++ code compiled by a programmer called Satoshi Nakamoto (most likely a pseudonym, and could be a group of people). In Nakamoto’s peer-to-peer currency paper that introduced Bitcoin to the world, a specific kind of decentralised ledger technology (DLT), called blockchain, was also introduced.

Imagine a system with no centralised authority where ledgers—records of accounts and transactions used by banks—are distributed among all the participants in that financial system. In blockchain, the ledgers are updated in blocks of entries—each of them time-stamped—linked to all of the previous entries. All entries are immutable—they cannot be amended under any circumstance. All the participant nodes in the system will maintain a continuously updated ledger. There are numerous versions of blockchains. They can be public and permissionless (like Bitcoin), or private and permissioned (which can be regulated in various degrees).

This decentralised concept offers both opportunities and challenges. How could a system work among a group of participants—there could be bad apples—if they were given the option of pseudonymity? Who will update the ledger? How will we reach a uniform version of truth?

Bitcoin solved a lot of the long-standing issues with cryptographic consensus methods with a combination of private and public keys, and carefully aligned economic incentives. Suppose User A wants to transfer 1 bitcoin to User B. The transaction data would be authenticated, verified, and moved to the ‘mempool’ (memory pool is a holding room for all unconfirmed transactions), where they will be collected in groups or ‘blocks’. One block becomes one entry in the Bitcoin ledger, and around 3,000 transactions will appear in one block. The ledger would be updated every 10 minutes, and the system would converge on the latest single version of truth.

The next big question is, who in the system gets to write the next entry in the ledger? That is where the consensus protocol comes into play. Bitcoin employs something called Proof of Work (PoW). It is akin to a race—the nodes in the system are pitted against each other to determine who can solve the complex mathematical puzzle to derive the block hash first. This process is called ‘mining’, and the miner who first solves the puzzle gets the chance to place the next block in the chain. The miner is heavily incentivised to be an honest player—if the block is validated by all nodes, she is rewarded with a certain amount of bitcoin. Once the block is placed, the transactions are completed and the bitcoins are transferred.

In essence, with PoW, your identity in the Bitcoin system—and your weightage in it—is directly proportional to the computational power you expend on it. The biggest problem with PoW is the environmental cost. Miners used as much energy as Finland’s total consumption last year.

The significance of Bitcoin

In a cryptographic sense, Nakamoto’s white paper precipitated huge advances. It was the first to propose a solid solution to the knotty Byzantine Generals Problem (a game theory problem that describes the difficulty that decentralised parties have in arriving at a consensus) within a global permissionless system, the issues of double spending (where the same bitcoin is spent twice), and Sybil attack threats (when an attacker creates a large number of identities to take over the system).

In an economic sense, Bitcoin leans heavily on the ‘deflation is good’ Austrian school of thought—libertarian, and against any sort of government intervention in markets—repudiating the prevalent neo-Keynesian and monetarist orthodoxy. For the Austrian theory advocates, Bitcoin is the only remaining version of ‘sound money’, which is something “capable of obstructing the government’s meddling in the currency system”, as economist Ludwig von Mises wrote in 1912.

For them, the fiat currency system (sovereign currencies with floating exchange rates) is essentially intrinsically valueless, and ripe for unbridled inflation and debasement leading to destruction of purchasing power. Bitcoin is the exact opposite—it is deflationary, it has a fully non-discretionary monetary policy governed by algorithms, it has limited supply, and, as long as demand does not dip, the price would surge.

The digital gold

In every metric, Bitcoin tries to take after the yellow metal. Gold is a finite resource. Bitcoin copies that scarcity in the digital domain—they are finite (21 million in total), and this cannot be changed. The more gold is mined, the harder it is to get. In a similar way, the more bitcoins are mined, the harder the process becomes, thanks to the algorithm. Every four years, miner rewards are cut in half, in what are popularly known as ‘halving events’. It is not impossible to synthesise gold from other elements—it is just that the power required for the process makes it prohibitively expensive. The same is the case with Bitcoin. The quantum of resources required to capture 51 per cent of the nodes (and thus the system) is substantially higher than any incentive.

The metaverse

On October 28, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, in the company’s annual Connect conference, announced the rebranding of the parent company into ‘Meta’. Not many were surprised. Zuckerberg had never kept hidden his fascination for the metaverse—a term popularised in the early 2000s by science fiction writer Neal Stephenson—or an ‘embodied internet’. You are ‘inside’ the web through an amalgamation of Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) technologies. In Facebook’s metaverse, you enter in and out of new worlds, where your avatar can participate in conferences, attend concerts, collect art and explore territories.

Zuckerberg shared tantalising fractals of a psychedelic realm where literally everything was possible, cracked a few jokes of him being a robot, spoke about his vision for interconnected virtual homes, virtual worlds and virtual workspaces, and played all the right notes for the right crowds. He spoke about the metaverse not being controlled by one company, about privacy, and the evolution of an “open, participatory economy where creators and developers can make new experiences, and unlock a massively larger creative economy than the one constrained by today’s platforms”.

It is not just Zuckerberg. Many companies, including Microsoft, are planning big forays into this space.

Currently, metaverses exist, though at a basic level, in games like Fortnite, World of Warcraft and Roblox. All these are dedicated worlds unto themselves running virtual barter economies worth millions of dollars.

How is metaverse connected to cryptocurrencies? Before delving into how the puzzle finally comes together, a brief understanding of the current state of the cryptocurrency market is necessary.

The crypto surge

From Bitcoin being the sole player in the blockchain ecosystem in 2009, cryptocurrencies have come a long way. There are some 10,000 cryptocurrencies traded on the open market now, most of them various shades of game-changing tech, pump-and-dump speculative assets or outright money-grab scams. The market is worth around $3 trillion.

In 2015, the Ethereum blockchain (currently the second largest in market capitalisation after Bitcoin), and its ether tokens, emerged on the market. Ethereum, with its principal ideologue Vitalik Buterin and seven other co-founders, had an entirely different vision. It did not position itself as a payment system, but a platform on top of which decentralised apps (Dapps) could be built. Ethereum was flexible, programmable and fast. Unlike Bitcoin, which did not recognise the outside world, Ethereum facilitated the transfer of all kinds of values—data, real estate, commodities and financial transactions.

The most important aspect of Ethereum was the phenomenon of ‘smart contracts’. They are self-executing programmes, an extension of the ‘if this, then that’ aspect of basic programming—statements get executed or rejected based on the fulfilment of underlying conditions. For instance, there could be a smart contract that mandates transfer of five ether coins from User A to User B if a certain sports team lost a match. Since the contracts were on blockchain, they were absolutely immutable and no party could challenge or renege on their commitments.

Ethereum and smart contracts sparked a surge of innovation. First came the decentralised finance (DeFi) sector. Instead of normal banks, DeFi had decentralised lenders like AAVE, Curve, Balancer and Compound that provided same services. You could deposit your coins and earn interests, or you could get loans.

This was followed by decentralised insurance companies like Nexus Mutual and decentralised exchanges like Uniswap and Pancake Swap. The rise of stablecoins (cryptocurrencies pegged to real-world currencies) and of Oracles followed.

Oracles are the medium through which blockchains, which are completely blind to any data off the chain, access real-time, quantified information from the outside world. For instance, if an insurance claim was made against a natural disaster, Oracles can verify the event and its time and forward the off-chain data to the DeFi insurance app.

After DeFi came non-fungible tokens (NFTs), which has sparked something akin to a mini-revolution in the entertainment industry. Though quite counter-intuitive, think of NFTs as the ability to own artworks, videos, songs or collectibles on the internet, with ownership records securely maintained and transferred via the blockchain. In simple terms, you can right-click and download all the gifs and pics that you want, but the monetary and other benefits accrue only by the person whose name is indelibly marked on the blockchain as its owner.

Proponents of NFTs claim the technology is revolutionary in two ways. First, it helps artists—especially emerging ones—escape the clutches of middlemen like record companies and art galleries who have always pocketed a lion’s share of the financial benefits. The artists could engage and enter into mutually beneficial agreements directly with the audience. Everybody from Amitabh Bachchan and Salman Khan to Eminem and Ellen DeGeneres have entered the NFT marketplace.

Second, on a wider scale, NFTs introduced an element of scarcity—the same attribute that gives Bitcoin its value—into the infinitely reproducible nature of the digital realm (you know how easily you can make a copy of a digital image or a song).

After NFTs came decentralised autonomous organisations (DAOs), the decentralised successors to limited liability companies (LLCs). DAOs are governed by rules written in code and have members with voting rights (they are open to just about anyone). They have a structure that eschews traditional company hierarchy and bureaucracy.

Ethereum still monopolises the NFT and DeFi sectors, but the grip is slipping because of the continuing irritant of high ‘gas fees’, or the variable charges paid for transactions on the network. Third-gen chains like Cardano, helmed by Ethereum co-founder Charles Hoskinson, are promoting themselves as completely scalable, sustainable solutions to Ethereum’s problems. Companies are increasingly setting up shop in competitors that advertise higher throughput at cheaper prices. Polkadot and Cosmos are working on making blockchains interoperable.

Ethereum, however, has undergone seismic changes to keep up with the times, switching to the Proof of Stake (PoS) consensus protocol and to a larger framework of Ethereum 2.0. It has also implemented updates like EIP-1559, through which it becomes more deflationary.

The Indian scenario

From India, a lot of entrants are making splashes in the cryptocurrency world. Polygon, helmed by Sandeep Nailwal and Jayanti Kanani, operates as the premier scaling solution to Ethereum, providing inter-connectibility to blockchains.

Co-founder and CEO Edul Patel defines Mudrex as an asset management company bringing high-performance investment products to everyday investors. “Earlier, these kind of investment products were available only for High Net Worth Individuals (HNI). What we are trying to do is democratise these investment processes and sell it to everyday investors. Our growth has been 30 per cent month-on-month, and have 50,000 active investors, and close to $25 million AUM,” said Patel. “In crypto, all companies are publicly traded from day one, which opens windows for investors for massive wealth creation. We have features like Mudrex Coin Sets [baskets of cryptocurrencies managed by experts] for that,” he said.

Aaryaman Vir co-founded Ludo Labs, an NFT project facilitating direct interactions between footballers and fans, out of love for the sport. “Ludo Labs has launched a collection of NFTs, which will give the owner the ability to interact directly with their favourite players. It has a lot of real-world utilities. These NFTs can be traded in on the Ludo Labs platform for something tangible. That could be a signed jersey, it could be a chance to meet or play football with your favourite star, play video games online, or engage in a Zoom call,” Vir said.

Chingari, India’s Tik Tok alternative, recently made its crypto foray with the release of its native GARI token. You can earn GARI by joining the social media network, uploading original audio, and viewing, commenting and engaging with the videos on the network.

GARI is an example of the emerging new promise of social tokens, and the growing culture of ‘tokenisation’. Suppose you are a creator or an athlete or even a major league sports team. You can release NFTs or social tokens that offer real-world perks, governance privileges, or a share of current and future success, and establish a symbiotic relationship with fans/audience/supporters.

“Ownership via tokens and communities is a powerful concept. It makes the whole system more participative. Your consumers and users become shareholders, and governance and policies become transparent. All of this creates new risks and challenges, of course, and it is certainly going to take some time, and a lot of experiments, for us to reach a place where everything works smoothly,” says Nitin Sharma, India partner and global blockchain lead at early-stage venture capital firm Antler Global.

This is exactly where Zuckerberg’s (and many others’) “new economy” narrative, and the intersection with the metaverse, comes into play. And, the larger concept of a new kind of internet called Web3.

The concept of Web3 can be understood in two ways, says Sharma. “One aspect of Web3 is ownership of platforms by communities, and value creation for developers and users [unlike the current social Web2 where all ownership and value creation is centralised in the hands of a few companies]. This makes the Internet more peer-to-peer. Alongside this, there’s the element of users getting complete control of their identity and privacy in a decentralised way, where their data is not used or monetised without their permission. Similarly, the layers of the Web infrastructure from storage to computing can also be decentralised,” he said. Antler Global has made a commitment to invest in 25 to 30 Indian Web3 startups in two years.

The most bullish of cryptocurrency observers speculate that all of these trends could converge in the metaverse, coming to full fruition in the digital world. In theory, in the metaverses, assets like Bitcoin could become the underlying reserve currency, Ethereum [or any of its competitors] could host the financial ecosystem, and NFTs could become the identity/ownership layer that decides everything from your digital avatar to the amount of virtual property you own.

“There is a new internet getting created with Web3. A financial system is getting built with DeFi. Bitcoin, Layer 1s like Ethereum and Solana, community tokens, NFTs and DAOs are all building blocks of Web3. Now, when Web3 also converges with other technologies like VR, AR, and AI, we get a rough equation of what the metaverse could look like,” says Sharma.

One of the earliest examples of Web3 philosophy in play is the Brave Browser. Unlike most internet browsers where you are treated to a constant barrage of invasive ads, Brave offers you the choice to opt in and view whatever ads you wish to see. In return, you get paid in Basic Attention Tokens (BAT).

But, is any of this possible on scale, or is it just wild speculation?

Promises and reality checks

Analysing anything related to cryptocurrencies requires nuance. On the one hand, you have the traditional financial investors and institutional economists, turning their nose up at any mention of the “magic internet coins”, dubbing the whole market as “intrinsically worthless” and a massive speculative bubble that can crash any time. On the other, you have cryptocurrency maximalists who hold lofty dreams of a brand-new world in which decentralised currencies and systems supplant every single “corrupt” institution in the world—from banks to governments.

The truth, as always, lies somewhere in the middle.

A lot of money and time is being spent by humans in the virtual world. The gaming sector offers a glimpse of just how much potential a metaverse economy holds. Youngsters every year spend billions of dollars in virtual gaming worlds for all sorts of ‘skins’, armoury and accessories. In 2018, the market for virtual skins was an estimated $50 billion, according to a Bloomberg report. Now, extrapolate the figures. The revenue possibilities for creating ownership and a global market for virtual items—catering not just to gamers, but the whole of the internet—could be immense.

Also, the gaming sector has been a reliable indicator when it comes to predicting churns in the tech sector. Concepts like ‘gold farming’, in return for real world barter value, were rife in games like Runescape in the 1990s itself.

Some of the earliest adopters of technologies like bitcoin were gaming systems—World of Warcraft had bitcoin as in-game loot in the early 2010s. Fortnite and Roblox were metaverses long before the term came into vogue. In 2020, rapper Travis Scott performed a virtual concert inside Fortnite, earning $20 million. Gaming is now leading the push into the more immersive forms of metaverse.

Then comes the immense possibilities of play-to-earn games like Axie Infinity—where you can own in-game assets and earn tokens like Smooth Love Potion (SLP) or Axie Shards (AXS) in return for the time you spend playing. From April to August, the number of users on the game jumped from 30,000 to a million.

The rise of GameFi (Game Finance) is crucial in more ways than one. The crypto sector as a whole is accessible only to the internet native, and its organs like DeFi only to the crypto native. Theoretically, GameFi could change that by introducing its cryptotokens to an entire generation of developing/rural economies just by playing a simple game on a smartphone.

Now, time for a reality check. In the last week of October, a new cryptocurrency hit the exchanges. SQUID, a play-to-earn crypto, inspired by the South Korean Netflix series Squid Games, became a global phenomenon. It launched at less than a cent, but rose explosively to trade at $2,856 in a week. A day later, the prices crashed 99.999 per cent, after the promoters of the coin took off with close to $3 million. Thousands of investors lost a lot of money. And it was just one of many such frauds.

Crypto is still a nascent market and it is prone to hellish dips and euphoric highs; sometimes crashing 60 to 70 per cent on the back of one Elon Musk tweet. There are no regulatory authorities and there is absolutely no regulation. From a customer perspective, this means you can get ‘rugged’ (rug pulled under you by fraud actors), face exchange hacks and hardware wallet hacks, and lose your wallet access, and there is absolutely no recourse available.

When it comes to the “philosophies” of Web3, former Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey is one of the vocal detractors. “You don’t own ‘Web3’. The VCs and their LPs do. It will never escape their incentives. It is ultimately a centralised entity with a different label. Know what you are getting into,” he tweeted on December 21. Along with questions of Web3 as a mere marketing moniker, there are also concerns on the possible “hyperfinancialisation” of everything, as a result of the tokenisation culture.

In addition, for all the lofty rhetoric of subverting state suppression, cryptocurrencies have not faced anything remotely close to nation-state retaliation. Only China has criminalised possession and mining of cryptocurrencies. Most countries have been ambivalent so far, but that may not be the case in the future.

India, where cryptocurrencies are in that grey area between legality and illegality, has often raised the threat of bitcoin as financing terrorism along its volatile borders. The Modi government has signalled it will soon implement official laws and regulations to govern the marketplace. Prime Minister Narendra Modi himself had warned in November that the technology should not be used to “undermine democracies”

There is need for some clarity, said Nischal Shetty, founder of cryptocurrency exchange WazirX, in an interview with THE WEEK in August. “One of the things I would really forward to, is if not regulation, some guidelines for the industry. It would give some sort of clarity to existing startups and ecosystem. If possible, bring in some regulatory oversight so that innovation can continue, while at the same time you can keep bad actors at bay,” he said.

Only one thing seems to be certain. The world is standing at the brink of a seismic change. The question is, which metaverse will we choose?