Look who walked into the new year with us—the virus, albeit in a new avatar. While a third wave was inevitable, as predicted by experts like K. VijayRaghavan, India’s principal scientific adviser, last October, the sudden surge in cases now “may be because the virus was waiting for the dawn of a new year to bite,” says Professor Gobardhan Das, head of department, molecular medicine, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

In India, in the first week alone, it infected an average of 1.12 lakh people daily—a 500 per cent jump from the daily cases reported the week preceding it. Ever since the third wave began on December 21, 2021, nearly 4,500 cases of the Omicron variant, the now dominant circulating strain that affects the upper respiratory tract as against the Delta variant that affected the lungs, have been detected across India (till January 11).

The last time India witnessed an exponential rise in cases was during the second wave—May 6, 2021, saw 4.14 lakh cases and there was an average of nearly four lakh daily infections for seven days. “I won’t be surprised to see India easily crossing that figure in the next week or so, given that the Omicron is at least 10 times faster than Delta that rocked us last year,” says Das. Globally, more than 25 lakh Covid cases were recorded on January 4, the highest ever since the pandemic began two years ago.

As of January 9, the reproduction number of Covid-19 for India stood at 4.03, much higher than the 1.69 recorded during the peak of the second wave. This means that a single infected person can now be expected to transmit the disease to at least four people.

Many frontline staff, including doctors, are also testing positive, leading to acute manpower crunch in several states. Nurse Labeena Lagey attended to Covid patients during the last two waves and is back in the Covid ward at Mumbai’s Jaslok hospital. “Earlier, all Covid patients were shifted to a separate building,” she says. “But, in the span of 10 days, all beds in the four-storey building are full, as are the beds in the separate ward that has been created in the main building. Although no patient is very serious, we are getting increasingly short-staffed as four of my colleagues tested positive in the last seven days.” The hospital is seeing double the number of patients it saw in December, says Dr Sunil Jain, head of emergency medical services, Jaslok hospital. “We are all taking our boosters,” he says.

And this is happening across hospitals in Mumbai, which has already recorded close to twice the number of cases reported during the peak of the second wave. At Fortis hospital, Dr Rahul Pandit, a critical care specialist, and his team have attended to “at least 300” Covid-positive patients in the last 10 days or so. Around 30 of the hospital staff tested positive in a week.

According to the Maharashtra Association of Resident Doctors, 287 resident doctors in Mumbai tested positive in the first week of January. At Safdarjung Hospital in Delhi, 150 resident doctors tested positive in the same period, says Dr Anuj Agarwal, general secretary of the hospital’s Resident Doctors Association. The stretch is evident from the fact that the Union health ministry has asked resident doctors to attend to patients even if they test positive, as long as they remain asymptomatic. “The patient load is increasing by the day,” says Agarwal. “Half of the beds in Safdarjung’s Covid ICU were occupied within a week.”

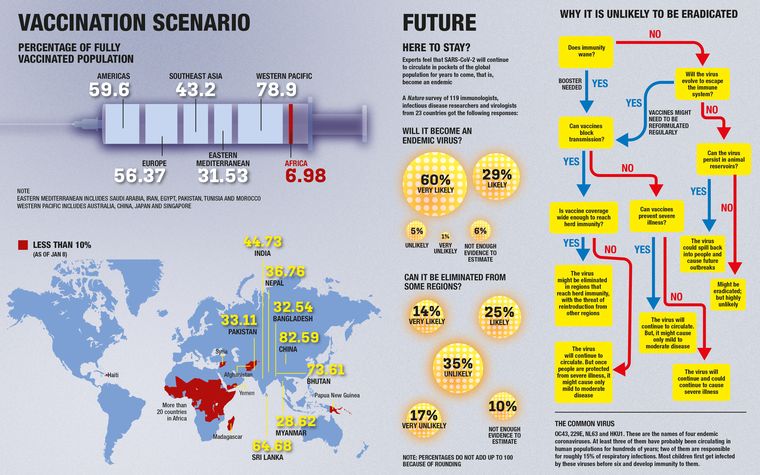

Some experts are calling this “the short but severe storm before the final lull”. “We are bracing ourselves for what is to come,” says Pandit, a member of Maharashtra’s Covid-19 task force. “The cases will keep rising until we peak, as witnessed in South Africa and the west. We are reaching towards endemicity, but not before we are put through the test a third time.”

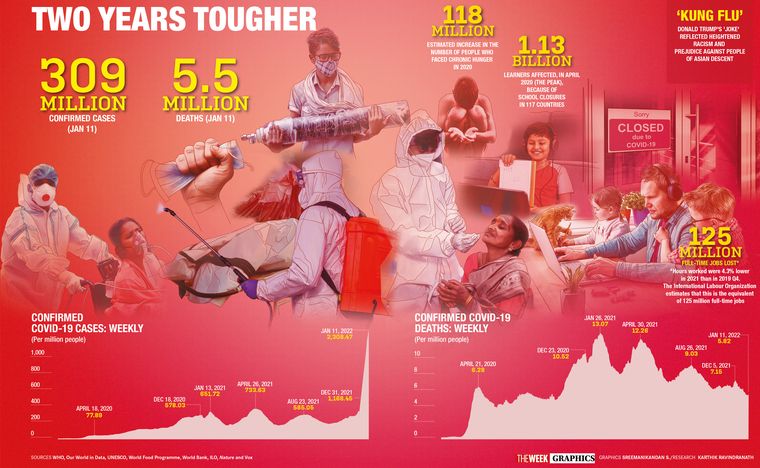

IN JANUARY 2020, the novel coronavirus seemed like a distant threat. Two years on, it has infected more than three crore Indians and killed nearly five lakh people. Worldwide, the death toll is 12 times higher. Just when we thought the worst was over with the waning of the second wave, in came the third wave. Schools are back to online mode again; staggered restrictions have been announced in several states; domestic air travel has reduced and offices have gone back to work-from-home—just like in March 2020. “Doing this all over again is depressing,” says Charu Mohanta, who is “frustrated” that her eight-year-old child is back to online learning barely a few months after in-person schooling had resumed. A fortnight ago, the Mohantas tested positive with “mild symptoms” at the airport just as they were to leave for a holiday.

Yet, two aspects give hope: One, unlike the previous two waves, Omicron is high on infectivity, “but low on fatality”, says Dr Avinash Supe, who heads Maharashtra’s Covid-19 death audit committee. Two, we have vaccinations. In the last two years, India has approved eight vaccines and administered 1.5 billion doses. More than 40 lakh children in the age group of 15-18 years received their first dose on day one of the inoculation drive, and the government hopes to achieve 100 per cent vaccination by May 2022. On December 28, less than a month after the first Omicron case was detected in Karnataka on December 2, India approved two Covid-19 vaccines—Corbevax and Covovax—and the antiviral drug molnupiravir for restricted use in emergency situations. And while there is not enough data on the efficacy of vaccines for kids, “it seems to be a safe bet due to the known technology as well as predictable adverse effects,” says Dr Srikanta J.T., consultant, paediatric interventional pulmonology and sleep medicine, Aster CMI Hospital, Bengaluru.

The two years of the pandemic, says Supe, highlighted the current inadequacies of our health care delivery system and the need for urgent improvisation. “From the government perspective, there definitely is an urgent need to increase the budget allocation for health care from the current 1.3 per cent to a minimum 3 per cent of the GDP,” he says.

The two years have seen us go through harrowing times—patients died for want of hospital beds and oxygen; ventilator supply ran dry; high infections led to severe manpower crunch at hospitals; there were not enough vaccines available then. Our health care system had crumbled under pressure, and our frontline workers, both in public and private hospitals, had burned themselves out. And now with cases rising, there is fear of a return to the past among health care workers.

“The mere thought that this will snowball into something bigger and the pressure that will follow is leading many to seek counselling,” says consultant psychiatrist Dr Avinash De Sousa. He has had “at least one case every day ever since the caseload began rising”.

BUT THERE HAS been a steep learning curve in between the waves. Doctors say the last two waves saw leading hospitals “come of age”. And now, hospitals are making themselves “pandemic-proof”. How? By creating state-of-the-art Covid management facilities; establishing self-sufficiency in oxygen building capacity; increasing bed capacity; augmenting infrastructure to ensure zero infection spread; leveraging telemedicine, remote patient management and emerging technologies; and taking to indigenous production capacities. With the increasing likelihood of new infectious diseases on the horizon owing to climate migration, creating facilities that can maintain operations during a pandemic has become essential, says Dr K. Hariprasad, president, hospitals division, Apollo Hospitals.

For instance, Apollo Hospitals introduced six-hour shifts, instead of eight-hour ones, and a duty rotation schedule to tackle exhaustion among nurses and floor workers in Covid wards. It took care of their travel, accommodation and food, too, and provided them with a Covid-19 risk allowance. A dedicated mental health helpline was also made available.

“Pre- and post-Covid health care will bear no similarities to each other,” says Dr Narottam Puri, FICCI Health Services, and former chairman, National Accreditation Board of Hospitals. “The transformation in the last two years has surpassed that in the last 20 years.”

India’s health care system, say experts, has embarked on a digital journey. As per a report by the Telemedicine Society of India, the number of online consultations went up three times between March and November 2020 and physical appointments went down by 32 per cent. As of August 2021, the National Telemedicine Service completed 90 lakh teleconsultations. Apollo Telehealth set up digital dispensaries in 100 primary health centres in Jharkhand.

Meanwhile, Meenakshi Mission Hospital & Research Centre, Madurai, equipped its security personnel with infrared AI helmets for contact-less body temperature checks of visitors and had safety robots keep the hospital sterilised 24x7 and carry meals to patients. This is part of the ‘Ultra Safety Program’ that uses cutting-edge tech for safety, says hospital chairman Dr S. Gurushankar.

Also read

- Covid-19 surge across Asia: What’s causing the spike in Singapore, Hong Kong?

- Fauci testifies publicly before House panel on Covid origins, controversies

- No pre-departure Covid test for travellers from China, five other countries from Feb 13

- Active cases decline to 7,175: Union Health Ministry

- Active Covid cases reduce to 12,307

- India records 625 new Covid cases, no deaths reported in last 24 hours

Experts have warned that in a country with a huge population, a small proportion of severe Omicron cases could put the health infrastructure to test. But a number of hospitals, big and small, have already boosted their infrastructure capacity. The P.D. Hinduja hospital in Mumbai has allotted 156 Covid beds across its two facilities in Khar and Mahim and has also maintained a separate building for Covid patients. “We are maintaining our beds across the two facilities,” says its COO Joy Chakraborty. “We will manage Omicron the way we managed the first two waves.”

Max Healthcare, meanwhile, plans to add close to 3,000 beds through brownfield and greenfield expansion in its hospitals in New Delhi, Punjab and Mumbai. And, Manipal Hospitals recently acquired Columbia Asia Hospitals and Vikram Hospital in Bengaluru. “In the last few months, we have established strong synergies with other stakeholders in the health care delivery ecosystem, which include government agencies, health care consumers and health tech companies,” says Deepak Venugopalan, regional COO, Bengaluru and Tamil Nadu cluster, Manipal Hospitals.

While the emergence of open-data initiatives that facilitate access to research data and scientific publications is helping hospitals collaborate, 3D printing is being used to address supply problems of ventilator valves, breathing filters, test kits and face shields. With the government easing regulations for drones, hospitals in tier 1 and 2 cities are hopeful of using the technology to spray disinfectants, conduct aerial thermal sensing and deliver medical supplies.

Hospitals are equipping themselves to administer newer drugs and therapies, too. Hiranandani hospital in Mumbai has administered the monoclonal antibody therapy for Covid-19 to more than 200 patients. “Symptoms improve within 48 hours and none of the patients has had a progressive course of illness if the therapy is given within the first five days,” says Dr Swapnil Mehta, consultant, pulmonology and sleep medicine, Hiranandani hospital.

AND EVEN AS hospitals are stepping up to the Omicron challenge, experts see a silver lining. “The filtered daily growth rate of cases at the national level has now plateaued at 34.9 per cent,” reads a report by University of Cambridge Judge Business School that has developed the India Covid-19 tracker. “This reflects the end of the super exponential growth phase of the current wave in a number of states and Union territories.”

Meanwhile, Deltacron, a new variant, has been found in Cyprus, raising doubts about an imminent fourth wave. But Das says that if Omicron continues to spread faster than Delta, then Deltacron will not be able to generate a wave. “In future, if at all it comes back, it will not be too severe,” he says, “and will hardly be found in a few places.”