Sourav Ganguly, the BCCI president, did not see it coming. Neither did selection committee chairman Chetan Sharma. The team and coach Rahul Dravid had no inkling either. Just like that, India’s most successful Test captain took off his crown and walked away from his throne.

On the evening of January 14, after South Africa clinched the Test series 2-1 in Cape Town, Kohli told the boys that it was time for him to go.

He then told selector Abey Kuruvilla, who was on tour with the team. The former India pacer was stunned. The selectors wanted Kohli to continue, but he had made up his mind. Sharma was informed immediately. Kohli, meanwhile, called up Ganguly and BCCI secretary Jay Shah.

The loss to the Proteas had hurt a lot. After wins in Australia and England, this was the ‘final frontier’, and India were tipped to win. It would have been another notch on his bat.

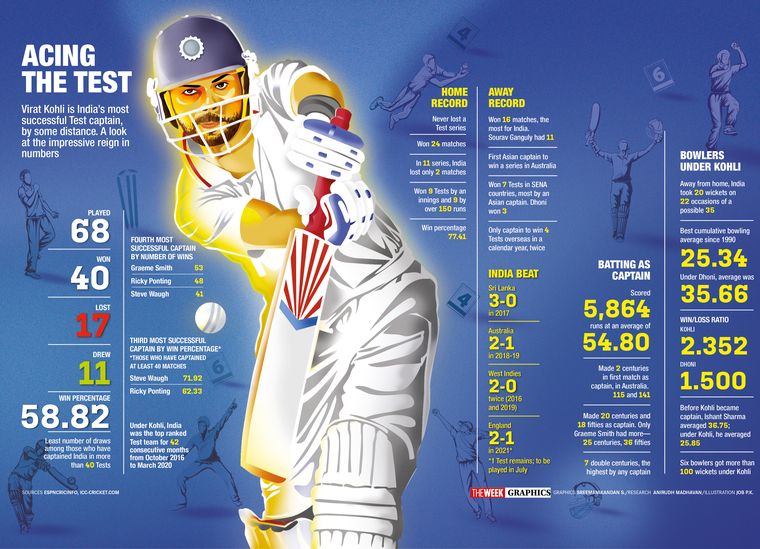

In his seven years as skipper, Kohli’s men had dominated at home and were competitive everywhere else. Kohli won 40 of 68 games as captain, had taken India to the top of the International Cricket Council rankings and had marched into the inaugural World Test Championship final.

Sure, a win in South Africa would have been great, but that is not the reason for the resignation. The seeds of discontent had been sown earlier. It had reached a point where Kohli was not enjoying being captain, or even his batting.

Reportedly, in the conversation he had with Ganguly after the third Test in Cape Town, Kohli said he was not waking up fresh and happy. So, he wanted out. He told the selectors the same.

“I have always believed in giving my 120 per cent in everything I do, and if I can’t do that, I know it’s not the right thing to do. I have absolute clarity in my heart and I cannot be dishonest to my team,” he had tweeted.

He had thanked the BCCI (he took no names), his teammates, former coach Ravi Shastri, the support staff and, lastly, former skipper M.S. Dhoni.

The call took many by surprise. Former India captain Kapil Dev told THE WEEK: “These days you do not get surprised by much. When he quit the T20I captaincy, one thought perhaps there was too much on his mind. From what we have read and heard, nobody wanted him to give up captaincy (then or now). He is a fantastic player; we should respect his decision.”

Former India coach Madan Lal called it a personal decision. “I feel he should have taken this decision a year later,” he told THE WEEK. “He has been the most successful captain for India. He was aggressive and brought in a fitness culture in the team. He has shown the world that India are a top test team. I do not understand why people are criticising him for not winning ICC trophies. As a selector or board official, I will not interfere with a captain who is getting results. He was definitely sore about the way the ODI captaincy was taken from him.”

Kiran More, former chairman of selectors, was more pragmatic. “I think every cricketer goes through this,” he told THE WEEK. “He has been a captain for seven years. There comes a stage when you think it is time to let go. There is always pressure when you are a skipper. It was his individual decision, not the selectors’. Rahul Dravid did the same when he was skipper.”

The BCCI responded to the decision with carefully scripted acceptance. Ganguly emphasised that this was Kohli’s personal decision. “He will continue to be a very important member of this team and take this team to newer heights with his contributions with the bat under a new captain. Every good thing comes to an end and this has been a very good one,” he said.

The winds of change had been blowing for the past two years, and they had fanned the flames. Before Ganguly and Shah stepped in, Kohli was all powerful. He had had a smooth, unquestioned ride for five years; then came the bumps. Kohli was able to fend off any “intrusions” till the time Shastri was by his side. But things unravelled much too quickly after he left.

Shastri’s reaction to Kohli walking away said a lot. “Virat, you can go with your head held high,” he tweeted. “Few have achieved what you have as captain. Definitely India’s most aggressive and successful. Sad day for me personally, as this is the team we built together.” He never wanted Kohli to give up the T20I captaincy, which he did last September, and was clearly unhappy with this call as well.

In between, Kohli was stripped of the ODI captaincy, and Rohit Sharma was named successor. What hurt Kohli the most, reportedly, was that the selection committee chairman told him he was being “removed” as the selectors were not keen on two white-ball captains.

What followed was a public contradiction of statements. A day after the selectors picked Rohit as ODI captain, Ganguly said that he had asked Kohli not to resign as T20I skipper with the World Cup around the corner.

In the media conference before heading to South Africa, Kohli said that nobody asked him to reconsider and that the BCCI top brass had called his decision “progressive”. He also said that he came to know that he was being removed as ODI captain 90 minutes before the selection meeting for the Test squad. “There was no prior communication,” he said.

The BCCI then fielded Sharma. In a news conference three weeks later to announce the ODI squad, he stood by the board’s version. “Everyone who was present in the meeting asked Kohli to reconsider,” he said. Though the BCCI has denied any gaps in communication, the events leading up to the South Africa tour showed in a bad light the workings of the board and the selectors.

Raj Kumar Sharma, Kohli’s childhood coach, told THE WEEK: “It is not a decision taken in haste. It surprised me, because I wanted him to continue for some more time.” He admitted that Kohli had, in the past few weeks, been concerned about the entire episode regarding the ODI captaincy. “But he was very clear that he wanted to step down,” he added.

There is no denying the fact that Kohli the person and Kohli the player defined Kohli the captain. They all feed off of each other. Thus, quitting the Test captaincy has to be seen as an emotional decision. The board and the selectors had no role to play in that call.

A very senior board official, who interacts with Kohli regularly, told THE WEEK: “[When] he stepped down as T20I captain, the board tried to persuade him not to do so. The board had no role in him stepping down as RCB (Royal Challengers Bangalore) captain either. Chetan Sharma had told him that the selectors did not want two white-ball captains on the morning of the Test squad selection meeting. It is very difficult to get him (Kohli) to change his mind once he has decided on something. He has a fixed mind. It was the same when the Anil Kumble (coach) episode happened; it is the same now.”

Reportedly, Sharma had also called Kohli when he got to know that the latter was going to step down as Test captain. But their conversations, apparently, have been few and far between, and Kohli has not encouraged such calls.

To understand Kohli’s “cussedness”, one must look to the time when he called all the shots. He got a free run in terms of making team decisions and picking players. He also had the results, the backing of Shastri and a non-interfering Committee of Administrators that Vinod Rai headed. He knew where he wanted to take his team and led from the front.

Over the past few months, though, Kohli reportedly felt that the board and the selectors were not backing him enough. That Sharma was brought in to refute his statement had hit Kohli hard. “He felt the BCCI was not standing by him,” said a source close to Kohli.

Said Dev: “They should have sorted out the issues between them. Pick up the phone, talk to each other, put the country and team before yourself.” He also said that, as a skipper, it is not necessary to get everything you want from the selectors. “In the beginning, I also got everything I wanted,” he said. “But, sometimes, you may not get it. That should not mean that you leave the captaincy. If he has left it because of that, then I do not know what to say.”

Differences with selectors vis-a-vis player selection was just part of the problem for Kohli; his own tepid run in Tests did not help. There is no doubt that the selectors and the BCCI were caught napping. They had not yet formalised the succession plan; after all, there was yet another ICC Test Championship cycle that Kohli was to lead the team in.

The board, though, is not too worried. Rohit is the front-runner for the job and K.L. Rahul is seen as a possible successor. Rohit, 34, is likely to be a stopgap captain. Former Indian captain Sunil Gavaskar has batted for the 24-year-old Rishabh Pant, but the BCCI bosses apparently feel that he needs more time before being given a leadership role.

“Why are we ruling Rohit out? He is a committed player,” said a senior BCCI official. “As for his recurring injuries, that is part and parcel of a sportsman’s career. In 2007, the selectors chose Dhoni out of nowhere to lead India in the first T20 World Cup. He was not even in the leadership group then. So, I do not think there is a leadership vacuum post Virat’s resignation.” The board is looking to groom Rahul as the Test vice captain, though the question of who will be given the reins eventually remains open.

If there is one positive that everyone would hope comes out of this, it is the return of Kohli the champion batter. “People running him down as a cricketer is not on at all. He will now play cricket dil se, just wait and watch,” predicted More.

Added Dev: “He is a fabulous player; [I want to] watch him play so much more and score runs, especially in Test cricket.”

There is, after all, the pesky question of century number 71.