Ranjana Malik, wife of former Army chief General V.P. Malik, still remembers that day in early 1998. Two young war widows walked into her office at the Army Wives Welfare Association in Delhi. “I do not want to live my entire life on my husband’s pension. I would rather wear his uniform,” 27-year-old Ravinder Jeet Randhawa told Ranjana. Ravinder was the widow of Major Sukhwinder Jeet Singh Randhawa, killed in action while leading a counter-terror operation in Jammu and Kashmir in 1997. She was accompanied by 25-year-old Sabina Singh; her husband, a helicopter pilot, had died in a crash in the northeast.

“The two young widows were told that they would get their husband’s full pay as pension for life. But they did not want that, they wanted to do something for the Army for which their husbands gave their life,” said Ranjana. “I was stunned to see their determination.”

Since there was no provision to induct them into the Army as war widows, and as they faced problems regarding age and marital status, Ranjana requested General Malik, who then headed the Army, to intervene, and he took up the case with the defence ministry.

After a few days, permission came through for them to appear before the Services Selection Board (SSB). Ranjana made it clear to Ravinder and Sabina that once they became officers, they would not be given any special concessions or preferential postings, even to take care of their young children. “They told me that they wanted to be like regular officers. Both took the examination and joined the Officers Training Academy (OTA), Chennai,” said Ranjana.

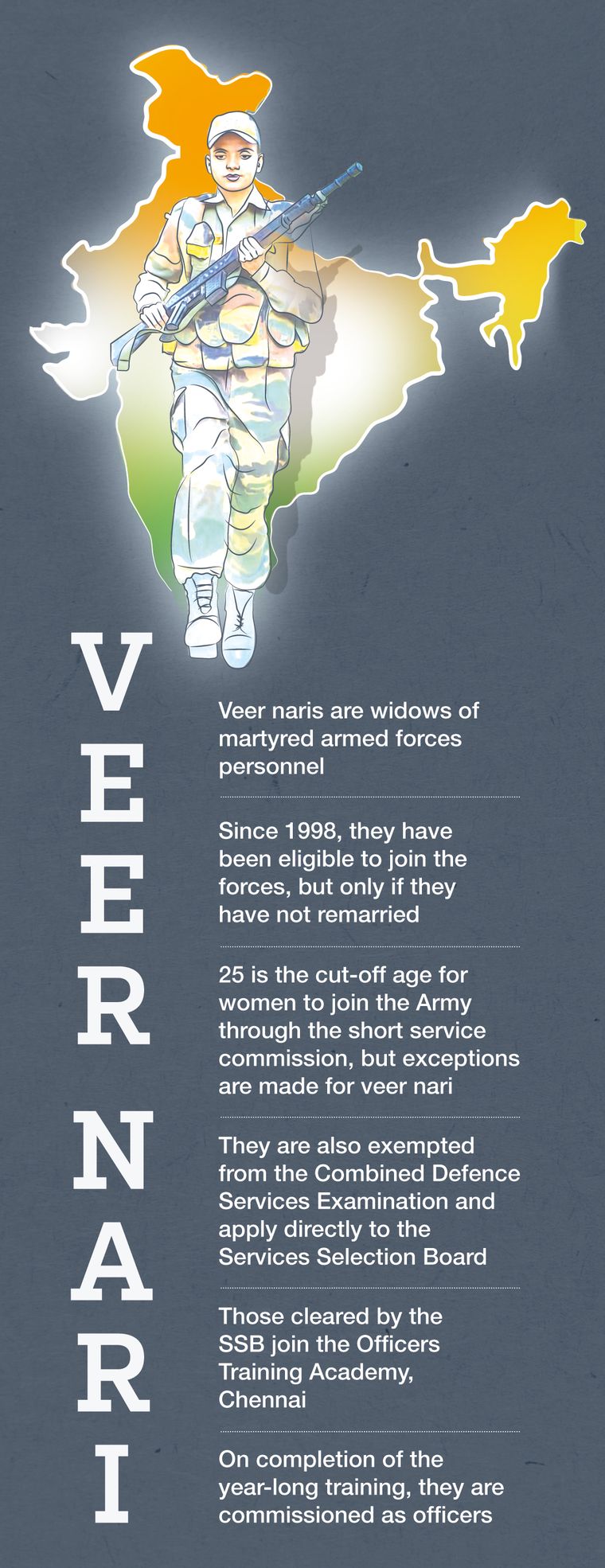

Ravinder and Sabina passed out from the OTA in September 1998, making the Indian Army the first in the world to commission widows of its fallen soldiers as officers. The widow of an armed forces member who has laid down his life for the nation, whether in war or in a military operation, is called a Veer Nari. And the armed forces want to ensure that their Veer Naris inspire pride, not pity.

The practice was initiated first by the Army, and the Air Force and the Navy have followed suit. To date, close to 50 war widows have joined the armed forces, with the Army having the maximum number of them among its ranks.

The induction of Veer Naris is done not out of sympathy or charity. First, the women have to prove themselves physically and mentally eligible, which is followed by rigorous training at par with any other officer. The only relaxation they get is in the qualifying age to be an officer.

As per rules, widows of defence personnel, including those with children, who have died in harness, are eligible to apply for short service commission. And it has a quota of 5 per cent of the total number of vacancies for women in short service commission. With the age relaxation of four years, a woman is eligible for such entry, if she has not remarried.

Ranjana feels proud of her achievement of opening the gates for war widows. “I set in motion something, which is going to be a great help to our widows to stand on their feet. Since then, many such women have donned the uniform.” During her tenure as the head of AWWA, eight more war widows joined the military.

Widows of jawans, too, can become officers under this category. Captain Priya Semwal was the first widow of a non-commissioned officer to join the Army. She was married to Naik Amit Sharma, who was serving with the 14 Rajput regiment. Sharma was martyred in a counter-insurgency operation near Tawang in Arunachal Pradesh in 2012. After being encouraged by her late husband’s unit, Semwal cleared the exams, joined the OTA, and was inducted into the Corps of Electrical and Mechanical Engineering of the Army.

With the growing number of applications, there is intense competition and many war widows are finding it difficult to enter the services. Heena Parmar’s husband, Lieutenant Colonel Rajneesh Parmar, was a helicopter pilot who died in a crash on the India-China border in September 2019. Parmar, 37, appeared before the Bhopal SSB in August 2020 and cleared all the tests. But she could not make it into the final list as there was no vacancy left under the war widow quota.

“I could not join OTA because there was only one vacancy in the non-technical branch, which was given to another woman. And, I am not allowed to re-appear before the SSB as there is no such policy,” said Parmar. “I have taken up the matter with the top military leadership, and I am waiting for a positive response.”