Lata gaati hain, baaki sab roti hain (Only Lata sings, the rest wail).

That cutting remark was made by composer Sajjad Hussain in an interview with Marathi writer Shirish Kanekar. Hussain was asked to comment on female playback singers in the Hindi film industry of the time. And, Hussain, blunt as ever, minced no words.

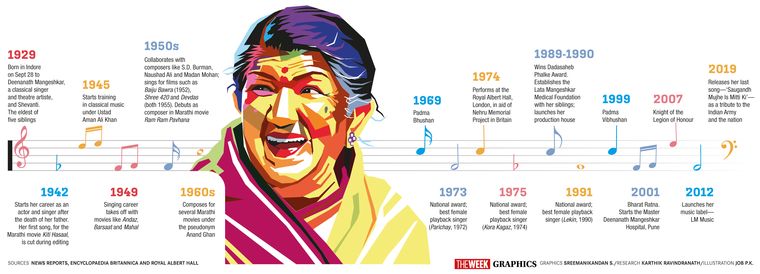

Though his remark ruffled many a feather in the industry then, it was a telling comment. For, no other female playback singer has reached the heights scaled by Bharat Ratna Lata Mangeshkar in her 70-year-long career. Her voice became her identity, and she the undisputed queen of melody. Her silken voice in songs of Mahal (1949), Barsaat (1949), Sangdil (1952), Anarkali (1953), Chori Chori (1956), Mughal-e-Azam (1960), Anpadh (1962), Woh Kaun Thi? (1964), Guide (1965), Abhimaan (1973) and countless others, gliding effortlessly from joy to anguish, from romantic pining to esoteric angst, could electrify, titillate, lull and seduce.

That mellifluous voice fell silent on February 6, incidentally the birth anniversary of Kavi Pradeep who wrote Lata’s most famous patriotic song ‘Aye Mere Watan Ke Logon’ that left then prime minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru in tears. Lata, 92, leaves behind a definitive testament to the capabilities of the human voice—its wide-ranging and profound potential as a medium of communication and a channel of emotion, one that speaks straight to the soul.

In the decades when sound waves were synonymous with Vividh Bharti, the country awoke to Lata’s voice over the radio. She sang ‘Jyoti Kalash Chhalke’ (Bhabhi Ki Chudiyan, 1961) at the crack of dawn. Then, as the nation settled in to its morning chores, they heard her latest offerings over Chitralok. At sundown, she was the answer to fauji bhai requests during Jaymala. Hers was the voice people took to bed, with Bela ke Phool. She became the magical night incarnate as she hauntingly sang, ‘Lag Ja Gale, Ki Ye Haseen Raat Ho Na Ho’ (Woh Kaun Thi?).

Lata was the voice to which our great grandmothers hummed ‘Hawa Me Udta Jaaye’ (Barsaat). She was the voice our grandmothers emulated when they guided us with ‘Aye Maalik Tere Bande Hum’ (Do Aankhen Barah Haath, 1957). She sang liltingly in the backdrop, ‘Dekha Ek Khwab’ (Silisila, 1981), as our mothers prepared breakfast. She was the voice of our schoolgirl desert dreams—‘Morni Baagan Ma Bole’ (Lamhe, 1991). In the new millennium, she prayed with ‘O Palan Haare’ (Lagaan, 2001).

Lata was the past and the present. She flowed with ease from vinyl records to cassettes, and now resides in our cloud playlists. And, she will continue into the future.

HOME IS WHERE THE ART IS

Lata’s gift of the raag was first spotted by her father Deenanath Hardikar; he later changed his surname to Mangeshkar as he hailed from Mangeshi village in Goa. Deenanath left the village to pursue a career in music and theatre. He and his wife, Shevanti, a Gujarati, had five children—Lata, who was named Hema at birth, Meena, Asha, Usha and Hridaynath, all of whom are renowned singers and musicians in their own right.

Lata was born on September 28, 1929, in Indore, but the family moved to Sangli when she was four. Lata’s connection to Indore would remain tenuous even later in life. She rarely visited the city in the last four decades of her life.

And, that was because of a ruckus during her show in December 1983. A concert to raise funds for an indoor sports stadium in Indore had been organised by a media baron. At the concert, chief minister Arjun Singh announced the ‘Lata Alankaran’ award in her honour. However, Suresh Seth, a Congress MLA who owned a newspaper and was said to be in the camp opposing Singh, objected to the government support to the programme.

There were black flags shown, and Lata decided to never perform in Indore again. She came to Indore only once later, in 2005, to visit the ashram of spiritual leader late Bhaiyyu Maharaj. BJP national general secretary Kailash Vijayvargiya recalled how his attempts, as mayor, to invite Lata to Indore had failed—something that would rankle him always.

But Madhya Pradesh’s loss was Maharashtra’s gain from the beginning. Deenanath had moved to Sangli hoping to earn a better living, as the king of the princely state, Chintamanrao Patwardhan, was a patron of music and musicals. Deenanath had changed his first-born’s name to Lata when he had heard her hum a song by a character called Latika from his famous play Bhav Bandhan.

But he noticed her keen ear for music and talent for singing only when she was six. During one of his music classes, he taught a student a particular raag and asked him to practise while he went out on an errand. Lata was playing nearby as the student practised. Suddenly, she asked him to stop and said, “This is not the way my father sings this raag; your rendition is incorrect.” She then demonstrated the correct way to sing it. Deenanath, who had returned by then, listened to Lata’s rendition spellbound and rushed to the kitchen and reportedly declared to his wife, “We have a musical genius in our house.” The very next day, he stopped giving tuitions and started teaching Lata instead.

Lata’s first stage show was with her father in Solapur, when she was just 9. Her father, recalled Lata in an interview, was strict and conservative. “Our clothes were also decided by him,” she said. “Kumkum lagana chahiye, haathon mein choodiyaan honi chahiye [Putting the red, round mark (akin to a bindi) on forehead was a must, as was wearing bangles]. My mother used to wear the nauvari (nine yard) sari.”

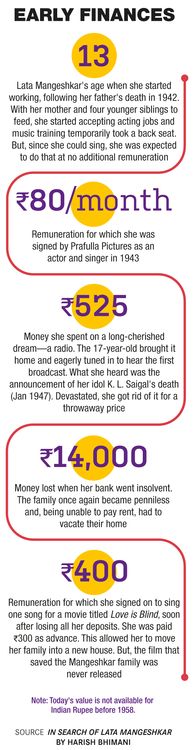

Her father died in 1942, and the Mangeshkars lived in Kolhapur for a while, with help from eminent filmmaker Master Vinayak. The family moved to Mumbai with Vinayak’s family. Lata’s first break in films came through Vinayak, who made her sing and act in his Pahili Mangalagaur (1942). She did several bit roles in Marathi films in the 1940s. “Acting karna zaroori tha [Acting had become a necessity],” she said. “I would get smaller roles, like the sister of the bride or the hero. I did not like those roles, but I had no other option as I was responsible for my [family].”

Lata did not like being dependent on Vinayak and doing small roles in films. She told him that her future was in music and singing. She soon convinced her family to move out and then started focusing on playback singing. She was around 17 then, and she continued to record songs till she was 89.

A WALK DOWN MELODY LANE

And, in this incredible stretch of more than 70 years, she became a household name for lingering melodies that symbolised excellence and purity. Be it the melodious ‘Aayega Aanewala’ (Mahal) or the devotional ‘Allah Tero Naam’ (Hum Dono, 1961), or ‘Kuch Dil Ne Kaha’ (Anupama, 1966), to the modern-day seductive and hypnotic ‘Hothon Pe Bas Tera Naam Hain’ (Yeh Dillagi, 1994), Lata rendered every format with her quintessential passion and swing. And in every delivery, the output remained constant, each piece exuding a complete mastery over rendition of that particular song that is instantly recognisable even today.

She trumped age with a magical combination of a gifted voice and devoted riyaaz (practice). In 2006, when she was in her late 70s, she rendered a mesmerising jugalbandhi in ‘Lukka Chuppi’ (Rang De Basanti) with A.R. Rehman, who was almost half her age at the time.

But initially, her voice was dismissed as unsuitable for playback singing. Eminent composer Ghulam Haider gave Lata her first break in the Hindi film industry in 1948. He took her to producer Sasadhar Mukherjee, who, when he heard her, said that her voice was too thin. Haider told Mukherjee that he would be making a big mistake by rejecting her. “This girl’s voice will rule for many years to come,” Haider reportedly told him.

His words came true the very next year when her songs in Barsaat and Mahal became super-hits. Kanekar, who knew Lata for many years, wrote in an article that after recording songs for Barsaat, Jaikishan of famous composer duo Shankar-Jaikishan had proposed marriage to Lata, which she politely declined.

Lata was only 20 when the enchanting and hypnotic ‘Aayega Aanewala’ catapulted her to success. Appreciation poured in from all and sundry—from classical music maestro Pandit Kumar Gandharva to All India Radio listeners who sent postcards. Even with ‘ Aayega Aanewala’, filmmaker Chandulal Shah was not keen that Lata sing it, but composer Khemchand Prakash put his foot down. Unfortunately, the discs that time did not carry the singer’s name but the character name of an actor, which in this case was Madhubala’s ‘Kamala’. Over the years, Lata helped cement the space for playback singers in the Hindi film industry and brought to it stature and eminence.

Within five years of Mahal, Lata established herself as every composer’s muse. “It was a time when everything just fell in place for her, like a bouquet,” says Kalpana Swamy, a Bollywood buff and music aficionado who co-founded Nostalgiaana Jukebox. “Talented lyricists who wrote meaningful and moving lines, music directors who dished out beautiful compositions, expressive actresses who displayed grace and elegance and Lata who breathed life into the songs. They all came together to create magic.”

Besides being prolific, her remarkably long innings at the top of her vocal prowess saw her singing for three generations of female stars. Take, for instance, Lata being the musical voice for Tanuja in Jeene Ki Raah (1969) and her sister Nutan in Anari(1959) to singing the zesty and peppy ‘Mere Khwaabon Mein Jo Aaye’ for Tanuja’s daughter Kajol in Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jaayenge (1995).

Dressed in white saris all throughout, with pearl and diamond earrings and a necklace to match, Lata became the embodiment of elan, purity and substance. Even the most provocative songs, for example ‘Aa Jaane Jaan’ (Intaqam, 1969), had the lilt and cadence of melody. Her songs for heroines who essayed the role of a mother continue to evoke sentiments even today. In may of those songs, Waheeda Rehman gave life to her voice on screen.

A COMPOSER’S DELIGHT

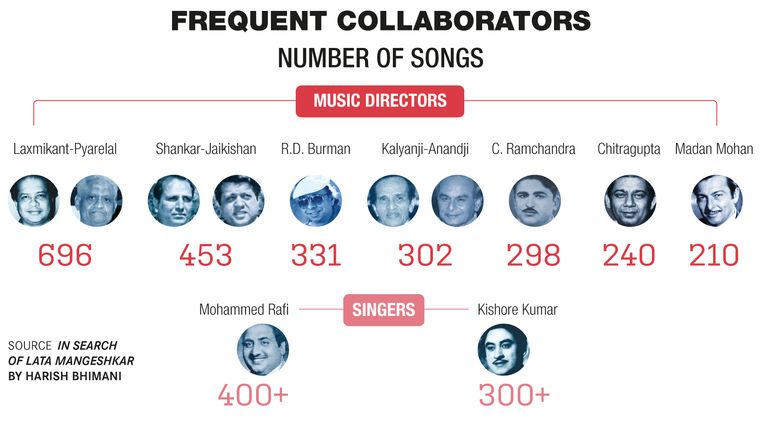

There was, no doubt, that she was every music composer’s favourite. Perhaps the only composer who admonished Lata was Hussain, who did so as she would not stop laughing during one of the recordings. Even O.P. Nayyar, the only composer of the golden age of film music who was decidedly against seeking her voice for his songs, would mention that Lata had a voice that was incomparable.

And, her association with Madan Mohan, whom she considered an elder brother, was like no other. It was only for him that she agreed to sing for a young Preity Zinta in Veer Zaara (2004), even after she had officially stated that she would not record any more songs. Those compositions were lying with Mohan’s son, Sanjeev Kohli, and when Yash Chopra got to know about it, he said he wanted to use them.

Mohan had always taken the risk of giving music to ordinary films and turn them into super-hits. He is also the one who exploded Lata’s vocal range, especially in ghazals and classical songs. It is said that he had waited 18 years to use his tune of ‘Naina Barse Rimzim Rimzim’ as he wanted the perfect cinematic situation for Lata to sing the song. He knew only Lata could do justice to that song and the opportunity presented itself with Woh Kaun Thi?.

The film’s music and songs became a rage in the mid-1960s. Lata thought that Mohan deserved an award for it, and when he did not get one, she was sad. But Mohan told her that her appreciation was an award in itself. Mohan eventually won the National Award for Dastak (1970) and the songs sung by Lata in the film are regarded as masterpieces even today.

Lata rarely sang cabaret songs. Her first cabaret song was ‘Aa Jaane Jaan’. She was picky when it came to her songs. As Kanekar wrote in an article, she refused to sing ‘Main Kya Karoon Ram Mujhe Buddha Mil Gaya’ in Raj Kapoor’s Sangam(1965). She found the lyrics to be too cheap. Kapoor had to plead with her for two days till he convinced her that it was not a raunchy song and took the story forward in the film. Only then did Lata relent.

Later, when Kapoor was filming Satyam Shivam Sundaram (1978), he assumed that Lata would lend her voice to the film’s songs. But, as Kanekar told a news channel, Lata and Kapoor had a dispute and were not on talking terms then. So, Lata refused to sing for the film and told composers Laxmikant-Pyarelal the same. Kapoor had to plead with seniors in the music industry like Pandit Bharat Vyas to convince Lata. She relented on one condition: Kapoor will not be anywhere near the studio while she recorded the song. Kapoor, despite his great understanding of music, had to agree. He stood outside the studio while Lata recorded the song.

For Pyarelal, who along with his brother has worked with Lata on close to 700 songs, there is no artiste like her. “We have been with her since we were kids,” he said. “She is a manifestation of goddess Saraswati.” Their association began in 1963, the same year when she sang and immortalised the song ‘Ae Mere Watan Ke Logon’ after the Indo-Sino war. “Her presence in the recording studio was electrifying,” he said.

Her love was the song; it did not matter who composed it or who directed it. Gujarati composer Gaurang Vyas told THE WEEK that he was surprised when Lata once cancelled her recording for renowned composer Khayyam so that she could record a song for him. It was the title song of Parki Thapan. “You needed freshness in the song,” she told Vyas.

Though her mother was Gujarati, Lata could not read Gujarati but understood the language when spoken. She had once said that she had learnt to sing garbas from her grandmother. There is more to her Gujarati connection—she never endorsed a product or brand except Vadodara-based Alembic Pharmaceutical Limited’s Glycodin, a cough syrup. The commercial, commemorating 60 years of Lata Mangeshkar and the pharma company, was shot by filmmaker Govind Nihalani.

Lata has also sung for directors who went into oblivion, and for films that tanked at the box office but are remembered for their music. Kamal Amrohi’s Razia Sultan (1983) is known more for its heart-wrenching music—think ‘Aye Dil-e-Nadaan’—than for the film.

Lata held her own in a male-dominated industry. And this is most evident in the song she sang from Manmohan Desai’s Amar Akbar Anthony (1977)—‘Humko Tumse Ho Gaya Hai Pyaar’. The mighty triumvirate of Mohammed Rafi-Kishore Kumar-Mukesh lent their voices to the three heroes of this multi-starrer; Lata alone holds her own, singing for all three heroines.

Lata has even composed songs for four Marathi films, under the pseudonym ‘Anand Ghan’. The songs from these films are quite popular in Maharashtrian households. She credited Marathi filmmaker Bhalji Pendharkar for her music composer stint.

LATA, LIVE AND LINGUAL

There is little to demarcate between a Lata Mangeshkar recording and her singing at a live event. She would replicate the nuances precisely in the latter. Lata’s first international concert was held at the historic Royal Albert Hall in London in March 1974.

Among the audience was a young Rajendra Darda, who later became education minister in Maharashtra. Darda was a student at the London College of Printing and could not afford the tickets for the show. “But I was fortunate to manage a temporary job as an usher for the three-show concert and enjoyed the programme from close quarters on all the three days,” he recalled.

“I remember the historical introduction to the show by the legend, Dilip Kumar, and that Lata ji seemed to be slightly tense at the beginning,” he said. “But once she had commenced the programme with a shloka, she went on and on with her mesmerising voice. The applause after each rendition was thunderous. It is an unforgettable memory.” In his introductory speech in Urdu, Dilip Kumar had said that Lata’s voice was a “miracle of nature”. Lata had first met Kumar during her struggling days in the 1940s, and it was Kumar’s comment on her Urdu pronunciation that prompted her to get Urdu lessons.

Lata was also fluent at singing in multiple languages with unfailingly good diction to internalise emotions. Take, for instance, her stint in the Tamil industry. She was first invited to sing a song in Tamil by none than other than Sivaji Ganesan. His son, Prabhu, was playing the lead in Anand (1987) and he wanted her to sing a song—Aararo Aararo—in it.

“My father and Lata ma shared a special bond,” says Prabhu. Lata and her sisters thought that Ganesan resembled their father, hence the instant bonding. She would call him ‘Anna (elder brother)’. Two weeks before her demise, Lata had shared images of ‘Anna’ over WhatsApp with Prabhu.

“In those days, there were very few hotels in Chennai,” recalled Prabhu. “Whenever Lata ma came down to Chennai and stayed in a hotel, she told my Appa that the food was not good. So, we would send her food from home. Later, she was unwilling to stay in hotels, so my Appa built a cottage for her inside our own Annai Illam. It was built in the Chinese style, and we call it the Chinese Room even now.”

Lata, said Prabhu, did not take a single penny for singing the song; she even paid for her flight. Every Diwali, the two families exchange greetings and gifts. Moreover, an illustration of Ganesan, drawn by Lata’s sister Usha, was reproduced on the wedding card of Prabhu’s son, Vikram.

But Lata’s super-hit song in Tamil was ‘Valai Osai’ from Kamal Hassan’s Sathya (1988). Music maestro Ilayaraja’s mesmerising flute, lyricist Vaali’s words, Lata’s melodious voice combined with S.P. Balasubrahmanyam’s emotive voice worked magic.

“I had a tune composed for my music album,” recalled Ilayaraja. “I explained the composition to Kamal. He liked it and said we can have it in the film. But I told him Lata Mangeshkar should come down to sing it. It was then that we sat down to write the lyrics. I asked lyricist Vaali to write the song. He heard the tune and was taken back. I told him that the words should repeat.”

Lata, he said, was initially not comfortable with the lyrics. “She asked me how could she sing it,” he said. “But I told her she could definitely do it. And after the recording, when she heard the song with the flute being played in the background, she became very emotional and extremely happy.”

Her ability to sing so beautifully in any language comes down to her training and practice. In a TV interview more than six years ago, when she was asked how much of her singing is natural talent and how much comes from practice, she attributed 75 per cent to talent and the rest to hard work, discipline and practice. A lot of thought went into food as well, but she said she did not follow food rules. “I have lemon, curd, chillies,” she said. “My father used to say that in singing, one needn’t avoid anything. The only thing that matters is that one keeps singing.”

Popular Chhattisgarhi folk singer Mamta Chandrakar, who is the vice chancellor of Indira Kala Sangeet Vishwavidyalaya, can vouch for Lata’s disregard for food curbs. She was doing her master’s in vocal music at the same university when Lata was given an honorary doctorate degree in February 1980. Chandrakar, a Padma Shri awardee, was among the batch of students assigned to look after and serve food to the guests. She was, however, worried about serving ‘Chattisgarhi kadhi’—a sour dish—to the singing legend.

“Reluctantly, I asked Lata ji whether I should serve the kadhi,” recalled Chandrakar. “She said she would love to eat it and did so. I was overjoyed. Everyone calls her didi, but I consider her as my mother. I feel her decision to eat food served by me was a blessing that has stood by me always.”

MORE THAN JUST MUSIC

She was a multi-hyphenate par excellence. She loved photography, enjoyed Formula One races, took interest in Ferraris and watched foreign films. She owned a bungalow on Fort Panhala in Kolhapur, where she had spent a few years of her childhood. Lata loved to travel to Kolhapur and Panhala where she spent time in the company of nature, shooting pictures of the beautiful scenery around Sharing a throwback picture from Rang De Basanti when she worked with Lata, singer Chinmayi Sripada recalled that Lata had a huge collection of professional cameras. “Not many knew about her interest in photography,” she said. “She had a fantastic collection of professional cameras and when we all came together she was talking about a new camera purchase.”

Cricket was another passion. When India won the World Cup in 1983, the Board of Control for Cricket in India wanted to celebrate the historic win but had no funds. So, BCCI president and Union minister N.K.P. Salve spoke to cricketer Raj Singh Dungarpur and requested him to arrange a Lata Mangeshkar Concert at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium. Lata readily agreed and the concert was a grand success. Around Rs20 lakh was collected, and players from the winning squad were given an award of Rs1 lakh each.

Sunil Gavaskar and Sachin Tendulkar were Lata’s favourites. In 1983, Lata was in London when the Indian cricket team was participating in the World Cup. She invited Kapil Dev and the team for dinner prior to the semi-final match with England. Soon after winning the World Cup, Kapil reciprocated and invited her for dinner.

In the 2011 World Cup, when India was playing Pakistan in the semi-finals, Lata fasted for a day till the match was won. In another instance, when Gavaskar, then captain of the Indian team, was attending a function in Lahore alongside the Maharaja of Baroda, Fatehsinghrao Gaekwad, he was introduced to Noor Jehan, a popular singer from Pakistan and a contemporary of Lata. The Maharaja turned to Jehan and said, “You may surely be knowing him? He is the Indian cricketer.” She replied in the negative and said she only knew Zaheer Abbas and Imran Khan. The Maharaja then asked Gavaskar if he knew Jehan, to which the cricketer cheekily replied that he only knew Lata Mangeshkar. A teary-eyed Lata was bowled over.

But Lata had deep love and respect for Jehan. Eminent music composer C. Ramchandra, in his 1977 Marathi autobiography Mazya Jeewanachi Sargam (The Symphony of My life), recounted in detail a historic reunion between Lata and Jehan at the no man’s land on Wagah border. He writes that Lata and he were in Amritsar working on Jhanjhar (1986) when Lata decided to call up old friend Jehan.

Both singing legends spoke over the phone and sang to each other for close to an hour. Once off the phone, Lata told Ramchandra that they simply had to meet Jehan in person. As their passports were not with them, diplomatic channels were used and a meeting at Wagah border was arranged, where the legends hugged tearfully and shared home-made food brought by Jehan. “The scene was indescribable,” writes Ramchandra. “Art knows no region, religion, caste or creed. Art means love and affection. If only the hearts of artists were as expansive as art.”

Lata also had a childlike innocence and playfulness to her. An idol for billions of fans worldwide, she was an ardent fan of popular television serial CID. Daya Shetty, who played senior inspector Daya on the show, told THE WEEK that Lata would regularly host the team members at her residence. She would remember the little details on the show and comment on the actors’ performance and their wardrobe. She even got some apparels of her choice sent out for the cast.

She was upset when the show went off air in 2018 and called up people at the channel to get it revived, said Shetty. “She was a wonderful woman, what can I say? She was a goddess in her own way,” he said. “She wasn’t a normal human being like us, but a divine soul full of selfless love.”

A VOICE THAT WILL LINGER ON

Death is that moment when people like to bring out unsavoury facets, often supposed, of a person, often even a strength of character in negative light. So, Lata was that ambitious person who snuffed out competition. And even if the charge is partly true, it only shows the strength, tenacity and resilience of a person who entered the industry as a penurious teen, then changed the rules of the game, remaining prima donna till she decided to step down.

Those who speak about the variety of female voices on air after Lata’s retirement do not mention that none of them has the staying power of Lata’s, which spanned at least five generations. Times have changed, people may argue, saying it is not possible to have such long runs any more. They forget that Lata lasted through several time changes, adapting herself to them.

The tech started changing somewhere around the late 1990, when electronically defined music came into the picture. So, for example, Mahal in which ‘Aayega Aanewala’ is sung, is pure vinyl or pure vintage. She sang linear for the longest time of her career. And so, when digital recordings came in, Lata was ready. In fact, as she was ageing, digitisation helped her stay fine-tuned even after her voice started deteriorating to an extent, as she could now record in bits and pieces.

In a career spanning five generations, it is natural to have fallouts with colleagues. Lata’s personal and professional relations, however, outlasted her differences. Many of her contemporaries and juniors alike vouch for her kindness and guidance.

Shabbir Kumar, who hails from Vadodara, has sung more than 50 duets with Lata. His first duet with Lata was for Betaab (1983). He was very nervous about performing with the legend and it showed. “I could not sing properly and there were takes on takes,” he said. Shabbir, who sang many songs for Amitabh Bachchan, said that Lata asked composer R.D. Burman to take a break. She then gave a cup of tea from her thermos and told him to sing as if some other lady was standing next to him and not her. There were no takes after that, he said.

Singer K.S. Chithra first met Lata at an event organised by a Telugu association. But Chithra was not invited for the event and had taken Balasubrahmanyam’s help to meet Lata. He had asked her to meet him at the backstage at 8pm. “I got a photo with her which I still cherish as a treasure,” recalled Chithra. She next met Lata at a Mumbai event, but it is the call from her that she cherishes most. Chithra had sung and recorded a few of Lata’s songs on a CD and sent it to her. When Lata first called her, Chithra thought her family was pulling a prank on her and ignored the call.

“But after sometime she called again and congratulated me,” recalled Chithra. “The CD was sent as a birthday gift to her by my husband. She congratulated me and said, “Bahut achcha tha (it was very good).” When Chithra and her family were shattered by the demise of her child, Lata consoled her and called her to be a part of an event in Hyderabad. “She told me that I should come out of the tragedy, and music should be everything to me. This one piece of advice keeps me going,” said Chithra.

Lata has had an impact on everyone she has met, be it celebrities or common folk. Saluri Koteswara Rao, Telugu music director, recalled meeting Lata in the early 1990s at an event by Balasubrahmanyam. “S.P. Balasubrahmanyam introduced me to her,” he said. “She looked at me and smiled. She had such a powerful aura that I could not even go near her. She was like a yogini. I was blessed to meet her. It was also an unforgettable experience to see her perform live at the same event. I could not work with her as I could not compose songs that would be apt for her.”

Devotional singer Shobha Raju had the honour of singing a Telugu song for Lata when she first met her at Tirupati in 1972. She was in her teens then. “I sang a Telugu song as I was scared to sing one of her songs. She was very happy and immediately blessed me,” she said.

The next time she met Lata was on stage in Hyderabad in 2010. “It was a great moment for me as I got to share the dais with her,” she said. “I observed that she got startled the moment someone sang in a high pitch. She was a very sensitive person.” When Lata fell ill two years ago, Raju conducted a puja for her health. “If there is a next life for us, I want to be reborn as her daughter,” she said.

For Telugu music director R.P. Patnaik, listening to Lata’s songs is like drinking nectar. “I met her once in Hyderabad. We interacted for a brief period,” he said. “Given her stature, I could not talk much. How can I even talk to her?” A regret he carries with him is having missed the opportunity to work with her. “I composed music for a Kannada movie, Ee Preethi Yeke Bhoomi Melide (2007). I wanted her to sing one song as I felt she would have been perfect for it,” he said. “It could not materialise as she was unwell that time.”

Latha Raju, a well-known singer in the south, wears her name as a badge of honour. And while she is aware that there may be many who were named after the legendary singer, she said that “there may not be many who could tell her that and get a smile back”.

Latha is the daughter of famous Malayalam singer Santha P. Nair. A recipient of Kerala State Sangeet Natak Academy Award, Latha, 70, is now settled in Chennai. She met Lata in 1980 during an interview with the All India Radio.

“Though I was not assigned the task, I insisted on joining the team,” recalled Latha, who retired as director (marketing) Akashvani-Doordarshan, Chennai in 2011. “My colleague who knew about my obsession with Lata ji agreed. I could not sleep for many nights in the excitement of meeting my idol.” According to her, the emotions that Lata brings to a song is unparalleled. “There was not a single blemish in her singing... not many get that,” she said.

Lata’s voice had purity, but in commercial cinema, a woman has to sing in many voices. Lata voiced the wonder of first love with ‘Mujhe Kisi Se Pyaar Ho Gaya’ (Bhanwara, 1944), the excitement of marriage with ‘Ye Galiyan Ye Chaubara’ (Prem Rog, 1982), the expectation of a child with ‘Jeevan Ki Bagiya Mehkegi’ (Tere Mere Sapne, 1971) and the loss of a child with ‘Lukka Chuppi Bahut Hui’ (Rang De Basanti). She was the resilient Mother India (1957) who sang ‘Duniya Me Aaye Hai Toh Jeena Hi Padega’, the disenchanted lover who moaned ‘Saiyaan Beimaan’ (Guide).

When critics felt she was not western or waspish enough, she sang ‘Kaise Rahoon Chup’ (Intaqam) in the voice of an alcoholic, with even the hiccup being a musical note. In the same film, she sang a cabaret number for Helen. Even during her golden reign, Lata left a lacuna, which only her sister Asha was able to fill and even carve her own special space.

Yet, as much as Lata was self-assured and winsome, she was also acutely aware of the baggage she had endured to arrive at the pedestal she had. That sentiment of lassitude comes across in an interview where she was asked if she would like to be reborn as Lata Mangeshkar in another life. After a brief pause, she said, “It is better that I am not born again at all. But if I do end up in an afterlife and if I am given a choice, I would definitely not want to be a Lata Mangeshkar because only she is aware of the difficulties and challenges that come with being her.”

A white sari, hair braided in long plaits and a silken voice marked the identity of India’s singing queen who represented a billion people and for them with superlative aesthetics in 36 different languages. An artiste of immense versatility and a conversationalist par excellence, her powerful voice, trained in the traditional Hindustani, charmed the audiences unequivocally. Those who know her best describe her as a soft-spoken and caring motherly figure who enjoyed good food, good music and social company.

There is no glass case around Lata. It is easy to listen to a song and imagine that she is singing directly from her heart. After 92 years of being around, even though she is no more there, yet she is everywhere. Just as they say there will never be another Mozart, another Tendulkar, there will never be another Lata Mangeshkar.

With Rekha Dixit, Lakshmi Subramanian, Nandini Oza, Rahul Devulapalli and Cithara Paul