There was a time, a year and a half ago, when Rishabh Pant felt stranded. Not like when he hops down the pitch and misses a wild swing. This was off the field. Critics were on his back, complaining that he was too inconsistent. There was reportedly not much support from captain Virat Kohli and coach Ravi Shastri either. Pant, 23, was out of the ODI team and was not the first-choice keeper in home Tests.

As for away Tests, he was dropped for the first one against Australia in December 2020. Wriddhiman Saha got the nod instead.

A disastrous Test later—India were bundled out for 36 in Adelaide—Pant returned to the team. Two weeks later, he had cemented his spot.

He had scored 89 on the last day of the fourth Test to hand Australia its first loss at the Gabba in 32 years. India won the series 2-1. Nine fours, one six and seemingly limitless self-belief; these were the ingredients that made that a once-in-a-career innings.

Pant had proven why he had been talked of as a long-term successor to M.S. Dhoni. He had clawed his way out of a career trough, and flew back to India his happy, impish self.

A year and few months later, he has reason to smile again. His personal growth aside, he has now found support like never before under the new team management. Pant had been nervous, what with his form and the uncertainty about his place in the team. Reportedly, he had even been told that Rahul Dravid’s arrival as coach might hurt his case. But Rohit Sharma, who has been close to Pant, gave him a lot of reassurance when he became captain, THE WEEK has learnt.

It also helped that Dravid had coached Pant in his Under-19 days. Reportedly, Dravid told Pant, Sharma and BCCI president Sourav Ganguly that he saw a big role for the wicketkeeper-batter in the team’s future. He also called up Pant before taking charge and had a lengthy conversation with him about his expectations. Pant also, reportedly, had a chat with Ganguly, who not only reassured him, but backed him publicly, too.

Four years after he got off the mark in Test cricket with, what else, a six, Pant has now matured. And the team management sees that. Speaking to THE WEEK in an exclusive interview, Pant looked and sounded older. The naughtiness is still there, but more contained. Taking care of yourself in the ultra-competitive and high-profile world of cricket can age you fast. “I do not want to leave my inner core, but at the same time you have to find a balance,” he said. “When there is a serious discussion, I have to be serious... In the past year or so, I have been making better choices.”

The 2021-2022 season has seen the coming-of-age of the batter, wicketkeeper, son, ward and friend. There have been hard knocks; some courtesy of life and some of his own doing. But through it all, Pant has built on the foundation he laid in Brisbane. In the past 14 months, he has scored two of his four Test tons, four of his five ODI fifties, and one of his three T20I half centuries. It might seem like a mixed bag, but the numbers hide a lot. “I do not focus on scoring hundreds,” he said. “If by scoring 97 I have done what the team needs me to do, and I have given my 200 per cent, I am fine with that.”

This must be music to his coaches’ ears.

He made his slowest Test 50 (105) at The Oval last September, and fastest, off 28 balls, in Bengaluru in March. Both innings were tailored to the match situation, and both were key to India winning.

Then there was also the audacious reverse sweep off James Anderson’s bowling en route to a match-winning 101 in Ahmedabad last March; a reminder that Pant will be Pant. “On that turning track, he took 90-odd balls for his first 50 and then got 40 to 45 runs in the next 10 or 12 balls,” India batting coach Vikram Rathour told THE WEEK.

The more impressive feat, arguably, was in the Cape Town Test against South Africa this January. He scored 100 (139) of India’s 198 runs and seemed to be batting on an altogether different pitch. The second highest score was Virat Kohli’s 29 (143). With that ton, he became the only Indian keeper to have scored Test centuries in India, Australia, England and South Africa.

“His batting is his batting,” captain Sharma told reporters following the recent Sri Lanka series. “There will be times when you smash your head and say ‘Why did he play that shot?’ but again we need to be ready to accept that with him when he bats. He is somebody who can change the game in 40 minutes.”

Rathour, who has been with Pant most of his career, said it was “key to gain his trust” and have constant conversations. “We all knew he was a special player,” he said. “He had seen initial success by playing his way—we all know he is a stroke player. Then his consistency went down. I told him that nobody wants him not to play his shots, we just want him to be more selective in picking the bowlers he wants to attack. He is a young kid, and it takes time. [You cannot] suddenly change the approach. Maybe he realised once he got dropped that he cannot play his way. We all know he will get out defending; that is not his game. Playing according to the situation is all we want.”

So what was the result of all these conversations and time put in? “He has suddenly grown up,” said Rathour. “Rohit and Dravid are in the saddle now, and he knows he is an important player in the India setup.... He has now matured as a player. He is getting better and better, but there is still a long way to cover.”

Off the field, tragedy struck Pant in November; he lost his coach and mentor Tarak Sinha, 70, to cancer. He had depended a lot on Sinha, a coach at Delhi’s famous Sonnet Club, after his father died in 2017. “It was like losing my father all over again,” said Pant.

Devender Sharma, Sinha’s assistant at the club and Pant’s go-to guy for anything cricket, said, “When news of Ustad ji being diagnosed with cancer first came, he was very disturbed. We even sent sir’s reports to him when he was in England. The doctor told Rishabh that it was best that sir get treated in Delhi or Jaipur. He was shattered when sir died; we all thought sir would fight it out. [But Pant] is mentally strong—even when his father died, he came back two days after the cremation to play an IPL game and scored runs.”

While in England, Pant also got Covid-19 ahead of the Test series last July. Those 10 days alone in quarantine at his uncle’s place, away from the team, were tough for the youngster. As has been the bubble life. Time away from family has been hard, and there is only so much that video games or Monopoly or catching up on news can help.

On the pitch, though, everything seemed to be according to plan. His resurgence and evolution, especially in red-ball cricket, has been heartening for all his backers in the BCCI and outside. Said former Indian keeper Saba Karim: “The fact that he held his place in the Indian side helped him evolve as a person. Ever since the England tour, he has realised not just his potential, but also what the demands of the team are vis-a-vis him.”

Karim, who is currently head of talent search at Delhi Capitals and has been associated with Pant from his early days in Delhi cricket, said he had seen improvement in the latter’s “match situation play”. “Overall, he seems in a much better space and is able to express himself better,” he said. “Plus, his demeanour on field has improved and has helped him grow.”

Former Indian keeper and chief selector Kiran More, who has worked with Pant at the National Cricket Academy, said, “The expectations of Pant were from his batting; there was a lot of pressure on him, but he backed himself and his game (as batter) has gone up for me.”

What sticks out like a sore thumb, though, is the zero in his century count in ODIs. Though he has looked more settled in the line-up than before, more is expected of him. Is there an issue with his approach? “Even Sachin Tendulkar took time to score his first ODI hundred!” said More with a laugh.

His role in white-ball cricket is more defined now, said Rathour. “He will be a finisher at number five or six, he knows that. Nobody is pushing him to get a hundred in ODIs. He will always be an impact player and if he is consistently getting 40-50 and winning it for the team, then that is fine.”

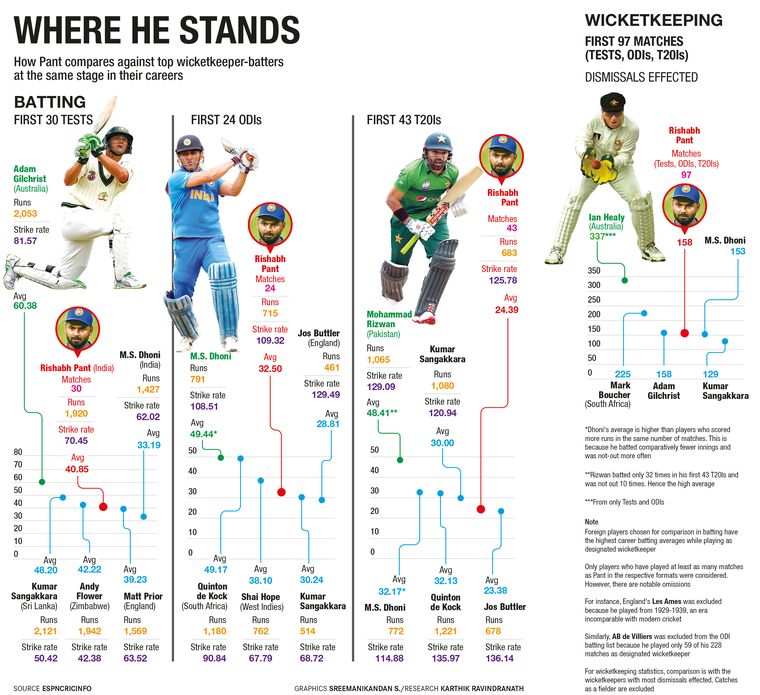

An aspect of Pant’s game is that his heroics with the bat often overshadow his wicketkeeping. It is a role that has seen quite some turbulence; in 2019, for instance, his home crowd at the Feroz Shah Kotla in Delhi showered him with chants of “Dhoni, Dhoni” whenever he erred behind the stumps. From there to now, there has been progress by leaps and bounds, quite literally. Karim said Pant has worked hard on match simulations and had vastly improved his footwork and collection of low catches. “He has been really good at gauging spin,” he said. “It shows his confidence behind the stumps. It was just a matter of time before he showcased his skills [as keeper]. He is now a multi-skilled player like Dhoni. His keeping has improved because his batting has improved.”

More added that a player had to be a good enough wicketkeeper to get into the team in the first place, and that keepers were like opening batsmen—there will be good and bad times. “His glove work has improved a lot,” he said. “His balance and positioning have also improved.”

Former India player and Delhi Capitals assistant coach Pravin Amre said it was the tour of Australia that gave Pant confidence. “Winning a series Down Under was so critical,” he said. “And then to win against England. That also boosted his confidence. His keeping has improved, especially at home. He has got maturity by playing tough series.”

Said captain Sharma: “His keeping [against Sri Lanka] was the best I have seen. He seems to get better every time. And he also seems to be making the right DRS (decision review system) calls.”

For the past few years, the competition among wicketkeeper-batters has been intense. While Saha’s career seems to be over, Ishan Kishan and K.S. Bharat are now in the fray.

More described Pant as a “very smart cricketer”. “He has a great mind, and his reading of the game and ball-to-ball awareness are sharp,” he said. “He is a lot more shaant (peaceful) while keeping.”

Pant’s chirping behind the stumps has been a source of entertainment for fans for years. He once sang a Hindi version of the Spider-Man theme, calls Ashwin “Ashley”, and even jokingly told Harsha Bhogle to improve his work so that people do not clamour for the commentary to be shut off when he is behind the stumps. Bhogle had brought up the “complaint” in a post-match interview.

“His composure is good,” said More. “He has grown for sure with more responsibility as India vice captain. I will not change anything in his batting; with experience he will realise what he needs to do.”

Pant was made deputy to Sharma for the T20I series against the West Indies in February. The national selectors are looking to groom future captains under Sharma, and Pant is one of the main contenders alongside K.L. Rahul and Shreyas Iyer.

More added that Pant did not believe in following anyone and did not have anyone in mind while leading a side. Apparently, so focused is Pant on his job as Delhi Capitals skipper that he shot down the management’s idea of making a documentary on the team this season. He wanted the team to focus on winning its maiden title.

Reportedly, he made it clear to the team management before the mega auction that he would stay on only if he was made captain. Shreyas Iyer had the same condition. The DC bosses chose Pant.

“When Rohit took over at Mumbai, he was quite a young man as well,” said DC head coach and former Australian captain Ricky Ponting. “He would have been 23 or 24, similar to what Rishabh is here. I know they are great mates and they talk all the time and they are probably exchanging things about leadership and captaincy along the way. I think there is every opportunity for Rishabh’s journey to be similar to Rohit’s. He’s a young captain of a successful franchise and growing on a daily basis. Hopefully, Rishabh can have the same sort of success Rohit has had at the Mumbai Indians (where Ponting has worked). With some experience in a high-pressure tournament like the IPL, I have no doubt there is every chance that Rishabh could be an international captain.”

The past year or so has been about Pant maturing as a player, he added. “The past couple of years with some more responsibility in and around the Indian team, and captaining DC, there is a lot of learning experience that will keep helping him become a better leader and person. I know Rishabh really well, and that is what he talks about all the time, trying to find ways to improve. He has got a good grasp on what leadership is all about because he has been in successful teams and he has been under strong leaders in the past.”

Being a full-time captain at DC, which comes with handling the pressure and expectations of team owners and fans, is a step towards bigger responsibilities.

Karim said communication and gut instinct were Pant’s strong suits. “He backs players, especially youngsters,” he said. “He likes to interact with the coaching staff, but on the field, he has a mind of his own.”

Pant’s rise has also meant a rise in his brand value. JSW Sports, which co-owns DC and also manages Olympic athletes, ventured into cricketer management by signing Pant—a move with an eye on the future.

Said Mustafa Ghouse, CEO, JSW Sports: “This (cricketer management) is a direct extension of the work already being done. We had a relationship with Pant (as a player) since we made an investment in DC in 2018; we have been interacting with him a lot. He was transitioning from his previous agency and the comfort level was there. It was always on the cards and we had a few conversations internally. We were not signing a big brand, but building the brand and growing with him. Rishabh fits the bill.”

Ghouse added that Pant was the next in line after Virat Kohli and Rohit Sharma, among current players, when it came to getting brand endorsements.

Pant, though, is not keeping track. At this point in his life, all he cares about is cricket. Performing in front of and behind the wickets. “International cricket is a journey, not a destination,” he said. “It is not about scoring runs in one-odd series, but doing so over a period of time. If I can do [what I have done] over 10 years, then I can say I have done something.”