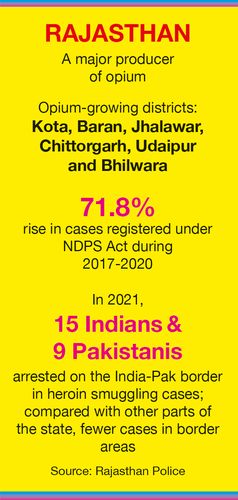

Come April, and vast swathes of poppy fields in Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Uttarakhand turn white. The spherical seed pods, with a dusting of white, attracts farmers and fowl alike. Even as birds—high on opium—throng these fields, Salim Khan, 45, an opium cultivator who has been charged under the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, heads to his field in the Pratapgarh district of Rajasthan. Here, he worships the white bulbs with incense sticks and prayers, before slicing them open six times for the latex—soft, sticky and bitter—to flow out. It is a ritual practised by thousands of opium farmers across the four states. Miles away, opium gardens in Afghanistan mirror the poppy fields in India as they enjoy a similar season and crop pattern. These fields and gardens provide fertile ground for the narcotics network to bloom far and wide.

Salim is aware of the drug network that buys his opium and smuggles it to Punjab, Jammu and Kashmir and further down to Gujarat, Maharashtra and other states. It is in these states that the opium changes hands and is mixed with alkaloids like acetic anhydride to make heroin and other narcotics.

An extensive probe by THE WEEK looks into drug markets and production and supply chains, from farmers to kingpins. THE WEEK found that the atmanirbharta in the illegal drugs industry is unmatched by any other sector. India produces enough for the domestic market and exports the rest. The illegal industry—right from the cultivator to end user, is very much within the country.

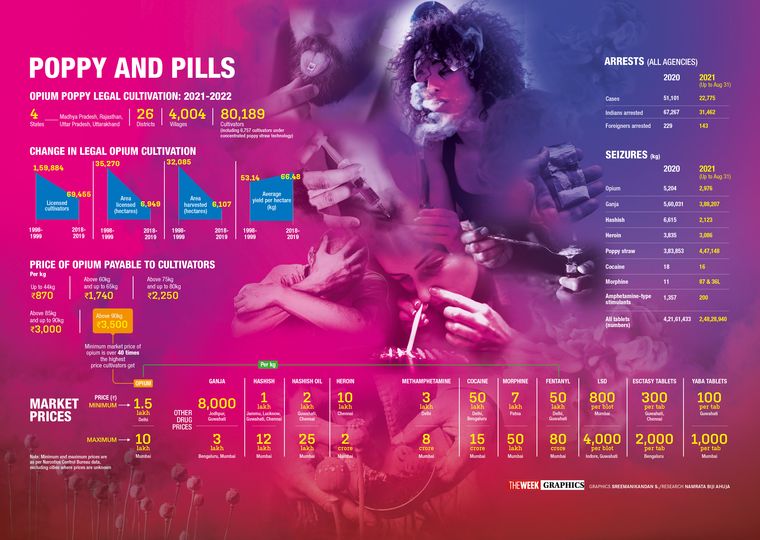

Presently, more than a dozen police agencies are chasing networks that run along national highways, through seaports, railways, airways, couriers and even the dark net. Union Home and Cooperation Minister Amit Shah said 35 lakh kg of narcotics worth Rs1,881 crore were seized between 2018-2021, three times the amount of drugs seized between 2011-2014 (Rs604 crore). According to Narcotics Control Bureau director general S.N. Pradhan, drug addiction in India is affecting roughly 8 crore-10 crore people. At least 19 narcotic drugs and tablets are freely available at different price points.

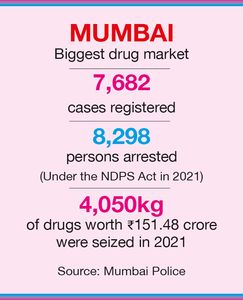

The recent recoveries made in Mumbai or the drug haul at Mundra port in Gujarat is only a drop in the ocean. For instance, ganja (cannabis) or weed, the consumption of which star kid Aryan Khan was accused of, is the second most popular narcotic drug in Mumbai, selling at Rs3 lakh per kg. Ruling the roost is mephedrone, at Rs20 lakh to Rs40 lakh. But heroin (Rs1.5 crore to Rs2 crore per kg) and cocaine (Rs10 crore to Rs15 crore per kg) are the all-time favourites of addicts.

In the fertile agricultural lands of north India, opium is legally cultivated in 26 districts of Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand, where the government grants limited licence to thousands of opium cultivators. Unlicensed cultivation plagues states like Himachal Pradesh and Manipur, but the tender care shown by farmers to get the perfect yield is the same. They nurture them day and night, sometimes sleeping next to them to protect them from the weather and ‘poppy-eyed’ birds. Once the buds are harvested, the leftover—known as ‘doda post’ (poppy straw) and has traces of morphine in it—is boiled and consumed as holy water, medical antidote or a celebratory drink by the local population.

“Growing opium is very expensive, hence the name kala sona (black gold),” said Salim, removing his shoes before entering the field. He takes out a curious-looking colourful knife and cuts the object of his love. “Each drop is precious,” he said. “The sourer the taste, the purer it is.” But he rues the fact that the government pays them just Rs1,000-Rs1,500 for a yield of around 50kg per hectare, whereas smugglers pay them Rs1 lakh to Rs1.5 lakh at least for the opium and an equally satisfying price for the poppy straw as well. The profit margins are huge and it is this desire to earn more that put Salim on the wrong side of the law several times.

“We have to keep an eye on him since he is a history-sheeter,” said inspector Dilip Singh Jhala of Rathanjana police station in Pratapgarh. “We call him regularly to the police station to ensure his activities are above board.” Salim smiles and says he has stopped breaking the law.

Salim is just a cog in the wheel of an industry that is malfunctioning at many stages—the legally cultivated opium in the country is either being smuggled to metro cities or rotting in government opium and alkaloid factories in Neemuch in Madhya Pradesh and Ghazipur in Uttar Pradesh, waiting to be exported for the last two years.

India has enjoyed the status of one of the biggest producers of legal opium in the world, but today it is coming back to bite it. “Till a few years ago, the international market for opium produced in India was huge in the pharmaceutical sector,” said a senior government official in New Delhi. “Countries like Japan, the US and some European nations used to import it but, of late, the trend has shifted, both domestically and internationally, to synthetic drugs, and there is no longer a demand.”

The disarray is such that the Central Bureau of Narcotics (CBN), under the Union finance ministry, is struggling to reinvent the wheel by trying out new technology to harvest opium gum instead of the traditional manual process called lancing. But this is not the only problem. “CBN officials visit fields to physically measure the area under poppy cultivation to ensure illicit cultivation does not happen,” said CBN superintendent Deepak Dubey in Mandsaur. But the CBN is facing a huge staff crunch, which makes matters more difficult for local police. To overcome these problems, the Central government is planning to drone-map all legal fields.

But M.L. Lather, director general of police, Rajasthan, said it is time to ban opium cultivation in the country. “It is not a very profitable crop,” he said. “It is only being grown to fetch huge profits from the grey market. The pitfalls are much more than the gain.”

Opium farmers, however, are unwilling to give it up as owning an opium field raises their social status. “It allows our daughters to get married into better families and is considered lucky, too,” said Kasam Ajmeri from Panmodi village in Pratapgarh. “My ancestors used to cultivate opium and my children are also learning how to do it. Why should I give it up as it is a matter of prestige for my family?” While growing opium is the culture in this part of Rajasthan, serving and consuming it is a matter of prestige in the Jodhpur-Jaisalmer-Barmer belt. In 2007, this practice had landed senior BJP leader Jaswant Singh in trouble when the opium drink was allegedly served at a function in his ancestral village, Jasol in Barmer district.

According to Amrita Duhan, superintendent of police in Pratapgarh, the danger lurking in these fields has transcended cultural and economic factors to become a major law and order menace. Investigations have revealed the criminal involvement of Afghan Pathans in nearby villages like Dewaldi and Naugaon, where they use traditional skills to refine opium into brown sugar and heroin. “Opium and its byproducts are landing in national and international markets through the networks of Afghan Pathans,” she said. “‘Doda post’ is further smuggled to those who use it for daily consumption.”

THE WEEK travelled to the infamous Dewaldi village, where the Afghan Pathans command fear, so much so that even the local policeman is scared of visiting the village alone. We are told that even before we set foot in the village, the Pathans were aware of our coming. “They have informants everywhere who tell them about any suspicious movement,” said Ajay Singh, station house officer at Arnod police station.

Gul Nawaz is a burly Afghan Pathan, with cases under the NDPS Act to his name. He says that his ancestors, led by Sardar Khan Pathan, had migrated to India from Balochistan decades ago and mastered the art of making brown sugar. When asked if he had inherited those skills, he said, “I don’t know anything about it. We don’t do any illegal activity.”

According to village records, accessed by THE WEEK, Sardar Khan Pathan arrived in Dewaldi with his four wives. Gradually, an entire community of Afghan Pathans displaced the local indigenous population, who are now living on the outskirts of this sprawling village. It happens to be the most well-off village in the district, with big houses that have high terraces to keep a lookout on passersby, and some of them have cars. The records document the long story of how this village grew in notoriety, with its men farming opium and making brown sugar and other narcotic substances and smuggling them across statelines and national borders. During police raids, they would fire at policemen, using women as human shields. The government has now banned Afghan Pathans from cultivating opium. But they are still the keepers of the secret of refining opium, and are said to be involved in gunrunning, sheltering criminals and reportedly have cross-border links in Pakistan. There is little evidence even today of how they procure the precursor chemicals used to make heroin or the methods they use.

Master Sher Ali, 88, the eldest in the village, agrees that there are problems. “The police treat us with suspicion even though I have tried to help them in many operations,” he said. “Some bad apples gave us a bad name.”

The Rajasthan special operations group, under senior IPS officer Ashok Rathore, has created fear in these unholy lands and slowly the drug corridor has now shifted from Rajasthan to Maharashtra and down south, where anti-terrorism squads of other state police forces are chasing and arresting smugglers. “Despite fencing across the international border, we are sensitive towards the ongoing activities at the border, as we have effected seizures to the tune of 50kg of heroin in the past few months,” said Rathore. “Simultaneously, action is being taken against smugglers with inter-state coordination and joint operations with other agencies.”

Recently, the Maharashtra ATS caught three drug lords from Dewaldi—Hakim Gul Khan, Jivanlal Bhai Tula Meena and Amina Hamaja Shaikh. Hakim, 56, and Jivanlal, 21, were arrested in October 2021 with nearly 5kg heroin. The ATS had launched an undercover operation to nab these two big suppliers who were visiting Dongri to sell heroin. The market value of the seized drugs was Rs15 crore. Amina, an unsuspecting woman, had been a key link in this supply chain in Mumbai for more than a decade. She procured the contraband from Hakim and Jivanlal and, through an active network of 10 peddlers, supplied the drugs in Ghatkopar, Worli and other places. Amina allegedly told the police that supplying drugs via road and railways was easier—they would keep the contraband in one compartment and book tickets in the next to avoid getting caught with the consignment. When the ATS laid a trap and arrested her the same month, she was carrying 7.2kg of heroin worth Rs21.60 crore.

In 2021, the Mumbai Police registered 594 cases of drug possession and 7,088 cases of drug consumption worth Rs15.14 crore. “As locality changes, the contraband changes,” Datta Nalawade, deputy commissioner of police of Anti Narcotics Cell in Mumbai told THE WEEK. “We find cough syrups and tablets worth Rs300 to Rs400 being consumed by the lower social strata, and MDMA, heroin, cocaine consumed by the rich and famous.” Nalawade said the opium-growing states are at the centre of the supply chain for drugs being smuggled into Maharashtra, and not the sea route. “We have not seen sea routes being used in any cases of late,” he said. “The drugs coming into Mumbai come by road or train, using cavities in vehicles like AC vents and bumpers [or] hidden in apples, dry fruits, even shoes, and carried by travel groups and bikers.”

Fayyum Mir Afzal Khan alias Faiz alias Raja, who is in the custody of Maharashtra ATS for a dozen crimes under the NDPS Act, preferred high heels for his drugs supply. Fayyum’s ancestral hometown was Peshawar in Pakistan. Born and brought up in Dewaldi, where his family owned a poultry farm and farmland, Fayyum, 28, also had family links in Chembur in Mumbai. He first entered the criminal records in 2012 when he and his friends went to Arnod Police Station and fired in the air. The police arrested 35 people from the village and he went to jail for four days. Six months later, two persons named Jahangir and Aleem came to his village looking for a man named Inayat Sher Ali and bumped into Fayyum.

“I asked them what the job was. They told me that they had come to buy heroin,” he allegedly told the police. “I did not give them Inayat’s address, but told them that I could sell the goods (heroin) they wanted. I knew that Raees Khan from our village was selling heroin and I supplied it.” When demand for heroin grew, he got calls from many customers. “I started buying high-heeled shoes and cut its heel to make space, put a plastic pouch filled with heroin in it and glued the sole back on,” he said. He would wear the shoes and board a train to Ratlam in Madhya Pradesh, and trade the shoes with Jahangir and Aleem at the railway station. The last time Aleem called him was on February 3, demanding 75g of heroin. The high heel shoes came in handy again. The only difference this time was that the shoes carried a mixture of Bimix, alprazolam, opium and a chemical for drying it to prepare heroin.

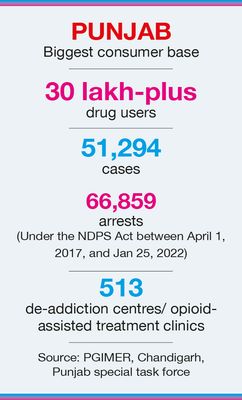

From high heel shoes to nameless and faceless drones dropping packets of heroin in Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir, the western frontier is already in the grip of a narco war. ‘Udta Punjab’ is a reality as it is facing an onslaught not just from within, with drugs being smuggled in from neighbouring opium-growing states, but from across the border from Pakistan as well. In some instances, plastic pipes were used to transfer drugs across the fence. In February, the Border Security Force killed three intruders in Samba district in Jammu and Kashmir and recovered 36 packets of narcotics worth Rs180 crore in the international market. The packets were being smuggled in through a plastic pipe in the middle of the night. “With the Indo-Pakistan border being completely fenced in Punjab and Rajasthan, the primary worry isn’t terrorist intrusions today, but narcotics smuggling,” said BSF deputy commandant Jaspreet Singh. In riverine stretches on the Jammu and Kashmir border, underwater nets and bars have been installed under culverts by security forces to thwart attempts to send narcotics by water. Moreover, farmers who have restricted access to nearly 20,000 acres of farmland close to the zero line are being bribed to deliver the drugs across the border.

Now, Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence and Pakistani Rangers have allegedly upped the game by using drones. Pakistani drones were first used in 2019 for delivery of arms and ammunition. They cost Rs25 lakh to Rs30 lakh and have a high risk-taking capability, owing to huge profit margins. Even if the drones carry out two to three successful sorties, its cost is recovered. “Drones are a game-changer in narcotics and weapons smuggling as they are beyond human capability to tackle,” said Jaspreet. “It is true that we don’t have foolproof technological solutions available with us, but few gadgets are under trial and with time we will succeed.”

The BSF is trying to beat narcotic smugglers at their game. “If drones can cover a maximum 3km, we are deploying boots, sniffer dogs and other force multipliers in those places,” said an officer. But the anti-drone technology being tested has its challenges. “There are commercial flights landing in Lahore,” said an officer. “The anti-drone technology has sensors that directs it to its target; we cannot take a chance with the Pakistani airfields being so close.”

Moreover, earlier Pakistani drones would fly at a lower altitude, but now they are flying almost a kilometre above, dropping packets and returning. “The BSF is regularly scanning and mapping the area for craters and spotting locations where receivers from the Indian side will go to collect the consignments,” said an intelligence official. “This gives us the opportunity to track domestic smugglers.”

There are mixed feelings about the Union home ministry’s latest move to extend the BSF jurisdiction to 50km in Punjab. “The change is made only under the Passport Act and not the NDPS Act,” said an official. “So in drug seizure cases, our jurisdiction is still limited to 15km in Punjab.” BSF officials feel lack of investigation power sometimes proves to be a handicap as the accused is handed over to the state police immediately.

One night, the BSF caught narco smugglers on its Long-Range Reconnaissance Observation System. “We saw them right next to the fence, but could not stop them as they were still on the Pakistani side,” said an officer. The commanding officer, a basketball player, felt so frustrated that the next day he took permission to leave the gate open at night. In this operation, 20kg heroin was seized. The lesson: man and machine must work hand in hand.

“Man, machine and the dog,” quipped Jaspreet. One such special operations team member of the BSF is Frooti, a sniffer dog who lives on the international border. Frooti starts barking even at the faint sound of a drone and runs towards it. Having undergone a six-month training programme, Frooti can hone in on low-flying objects. Frooti has now got canine company—BSF personnel are relocating street dogs to the border for drone detection.

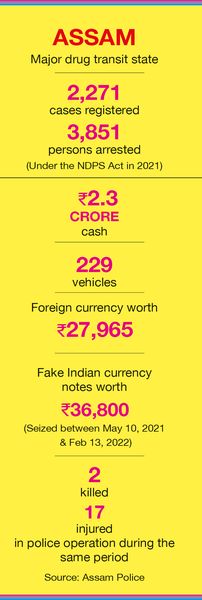

The narcotics routes, however, are not limited to the western frontier. The Golden Triangle, also known as the triangle of death or the black triangle, is using newer syndicates, especially women from areas bordering Mizoram, Manipur and Assam to route narcotics through the ‘Chicken’s Neck’ into Assam and further into the hinterland. The Golden Triangle earlier consisted of Laos, Myanmar and China—the hilly terrains being a perfect place to manufacture drugs. Initially, the Shang dynasty of China used to run the drug trade, but after 80-90 per cent drugs started ending up in China itself, the Chinese authorities took action. Today, the network operates in the mountainous terrain of northeastern Myanmar, northern Thailand, northern Laos and northeastern Vietnam, where heroin is manufactured.

According to rough estimates, 70 to 80 per cent of it goes to North America and western Europe and 20 to 25 per cent travels into India. The first stop is Guwahati, which is today the biggest transit and consumption centre in the northeast. Here, apart from the usual carriers like trains, trucks, car dashboards and AC vents, baby diapers and women themselves are being used to smuggle drugs.

The trend of women in their 50s and 60s acting as drug ‘queenpins’ has grown in Karbi Anglong district on the Assam-Nagaland border. Th Paone, alias Didi, is a suave woman in her early 50s who had given the slip to the Assam police many times. Dressed in bright clothes, with just a handbag in tow, she would shuttle between Dimapur in Nagaland to townships in Assam, a route taken by many ordinary folks to earn a living in the commercial hub. Her alert, piercing eyes would always be on the lookout for plainclothes policemen as she carried consignments of heroin made in Myanmar into Manipur and storage hubs in Dimapur. She started off as a one-woman army, but soon created a band of peddlers, middlemen and cross-border drug lords. She had been elusive for long. But Didi was lured out of her Dimapur house with a Rs7 crore deal on June 17, 2021. A police squad, led by Karbi Anglong Superintendent of Police Pushpraj Singh, had laid a trap for her with the help of their source in Dimapur. “Didi arrived with 164 packets of heroin in a car with an accomplice in Ganakpukhuri and was apprehended with the drugs,” said Pushpraj. “She was extremely slippery and was one of the main [players] in the supply link from Myanmar.” Didi is presently lodged in the district jail in Karbi Anglong.

Rozy Rongmei, meanwhile, ran a joint venture with her husband, Phungam Kamei. Inter-state drug smuggling got easy as Kamei, 61, was from Manipur—the marriage helped coordinate the drug racket better. When interrogated, Rongmei, 55, said it was a profitable venture.

Years ago, Lakshmi, 58, and Panjavarnam, 66, had shifted to Manipur from Tamil Nadu to ferry narcotics from Myanmar to Sri Lanka. Naturally, the profits grew when drugs crossed two international borders. But their method was simple. The two women, arrested in June 2021, revealed during interrogation that they colluded with transport operators. At the time of arrest, they had kept 3kg crystal syabu, a type of methamphetamine, in polythene bags that were concealed in secret chambers inside the engine compartment of a bus. The bus driver was part of the drug ring.

There are young women carriers, too, with babies in their arms to ensure greater camouflage. This method has also made smuggling small proportions of narcotics faster. On February 28, the Assam police arrested Suhitam Begum, 19, and Sakina Begum, 30, with 12 vials of heroin hidden in a baby’s diaper. The operation was difficult since it involved young mothers. It is now being used as a case study by the Guwahati Police.

Partha Sarathi Mahanta, joint commissioner of police, Guwahati, told THE WEEK that drug cartels continue to change their tactics because of the heavy profit margins. “For example, the Yaba tablets or The World is Yours tablets, sold for Rs200 in Assam, would cost Rs2,000-Rs2,500 in Bengaluru or the northern states,” he said.

Assam cannot beat the problem alone and, being a transit state, has to carry out joint police operations. “We have arrested people from Meghalaya, Manipur and even Delhi by sharing intelligence with other states,” said Mahanta.

Harmeet Singh, commissioner of police, Guwahati, said efforts are on to not only monitor the supply chain but also to catch the big fish, which is a much more difficult task. “The drug mafia is organised in such a way that only the kingpin has the complete picture,” he said.

And, there are plenty of big fish on the drug scene, most of these are today running the maritime drug trade, giving sleepless nights to the NCB in New Delhi. “There is every reason to be alarmed by the maritime trafficking of drugs right now,” said NCB chief Pradhan. “The data on all imports coming to India indicates that bulk of them are coming through containers. Seventy per cent of heroin is also using the container route. So this is a big modus operandi and needs close coordination between the coast guard, Navy, maritime boards of states, public and private port authorities and police agencies.”

In January, the NCB recovered 90 packets of American marijuana from Mundra port. In September 2021, nearly 3,000kg of heroin worth Rs21,000 crore was seized from the port; the consignment had possible links to terror groups in Pakistan and Afghanistan. The National Investigation Agency is probing how the proceeds of drug trafficking were sent back to foreign entities through hawala networks for use in anti-India activities.

The eastern coast is equally under threat. On January 18, Sri Lankan navy intercepted a Sri Lankan boat—Suresh 2—and found 300kg of high-quality heroin. Besides the involvement of Sri Lankan smugglers, the Indian Ocean has a mix of nationalities, from Iranians to Maldivians. In October 2021, Maldivian authorities seized more than 300kg heroin and arrested a dozen people linked with the drug network. In November 2021, Seychelles authorities intercepted a local speedboat from their exclusive economic zone with 147kg heroin. These operations have also indicated a possible reverse flow of precursor chemicals from India into the drug markets abroad, from where the drugs were also being smuggled back into the country.

Another gold mine for narcotic smugglers in the country is the postal, courier services and the dark net, which has grown at a lightning speed in the last two years of the pandemic. “The increase in dark net trafficking of drugs involving cryptocurrency and parcels has increased a 1,000 per cent over two years,” said Pradhan. “The traffickers have tasted blood. They realised there is full anonymity, full deniability and an ease of doing business. It is a very sinister and deadly combination, which is going to increase in the future. We don’t have the training and the wherewithal to handle it yet.”

The demand for synthetic drugs, meanwhile, is also rising exponentially, adding to the list of narcotic drugs already available in the Indian market. Also, both India and Afghanistan will be sitting on an excess of opium stock at the end of this year. The Taliban, however, announced a ban on poppy cultivation and harvest on March 3. The ban is threatening to pump up prices of narcotics in India, which is the closest market and transit route for drug trade in the region. “The ban will only increase the demand in the flourishing narcotics market, which will put more pressure on drug cartels who will be using the Pakistan route to push drugs into the country,” said B.V. Kumar, former director general of the NCB.

While the Taliban decree said that the crops would be burned and farmers jailed if they proceed with harvesting, Kumar said that there was no evidence of the cultivation being stopped. “Where is the national action plan on how it will be destroyed, where are the crackdowns on drug cartels, inter-state and cross-border measures to stop its smuggling outside Afghanistan?” he asked. “In 2000, Taliban had banned poppy cultivation, but it faced a huge domestic backlash from farmers, suppliers and businessmen involved in the trade, and status quo was maintained.”

Also read

- Why did NCB issue its first Interpol Silver Notice against mastermind behind the ₹2,500 crore Delhi drug smugglig case?

- 70% drugs reach India through ports

- We will use maximum force to stop drug peddling

- Zero tolerance towards politician-police-drug mafia nexus

- Government should ban opium cultivation

Today, the opium lords of Afghanistan are either part of the Taliban 2.0 government or have been instrumental in bringing it back to power. The biggest example is Gul Agha Ishakzai, finance minister in the Taliban government. He is said to be close to Quetta-born Taliban financier Ahmed Shah Noorzai Obaidullah, whose name figures on the UN sanctions list for narcotics trade. Ishakzai’s role has been under the scanner of anti-narcotics agencies since the Taliban’s takeover in August 2021. “So while the Taliban is trying to make all the right noises to gain international legitimacy, it can ill-afford to ban cultivation of opium to control drug trade,” said Kumar. “It is the global hub in the international supply chain of narcotics and a large part of its revenue comes from public consumption.”

The Interpol pegs the opium economy in Afghanistan between $1.2 billion to $2.1 billion a year. The ban, therefore, is seen as a token measure to appease the international community to revoke sanctions that are hampering the country’s banking and business sectors. For India, the bad news is that the scent of poppy will also attract terror outfits and financiers in the most notorious global drug route.

The ever-growing drug market in India is not just a matter of worry for the government, but also the public. Recently, Bollywood superstar Shah Rukh Khan ran from pillar to post when the NCB refused to meet him after his son Aryan was arrested in the Mumbai drug cruise case on October 2, 2021. The sleuths had given other parents a hearing, but King Khan was kept away. Upon intervention of a senior officer, Khan was granted an audience. He was told that consumption was an equally punishable offence as cultivation or purchase. Aryan, however, reportedly told the sleuths that they had mistaken his foreign girlfriend’s number for an overseas drug link. Indeed, sleuths still largely look out of the country when they stumble on high-profile drugs cases. Sooner than later, the government will have to turn its gaze inwards and clean up its own backyard if it wants to fulfil its vision of a “drug-free India”.