It is a majestic sight. The pristine blue waters of Pangong Tso ruffled by the icy winds blowing across eastern Ladakh. The contrasting hues of the arid mountains that ring the lake add to its resplendence. Although it is a saltwater lake, Pangong Tso freezes over in winter. The ice usually disappears by the end of April. This year, however, the thaw came early; locals blame it on global warming.

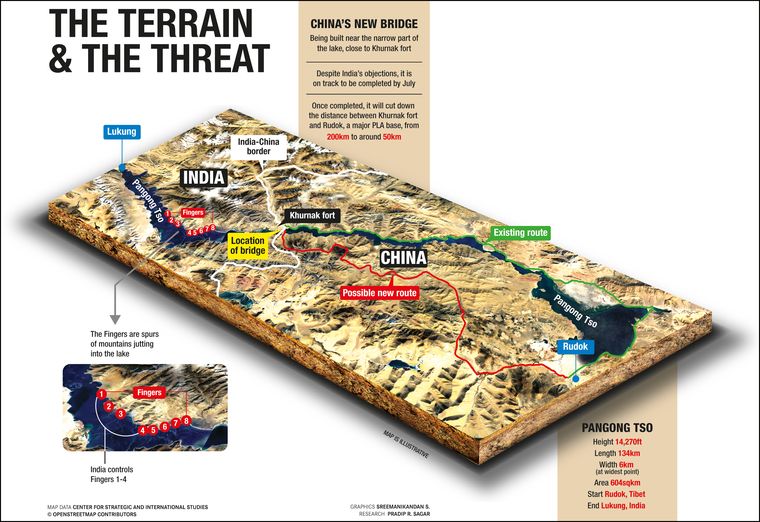

A thaw in India-China relations, however, seems unlikely as Pangong Tso is embroiled in yet another crisis. On May 20, the ministry of external affairs confirmed reports about China building a second bridge across the lake. The MEA statement said the bridge was being built in territory illegally occupied by China. It is coming up near the ruins of the Khurnak fort, built in 1867 by the Changpa tribes of Tibet, on the north bank of the lake. Till 1958, the fort and the premises marked the Sino-Indian border where the Indian Army had an observation post. The Chinese overran the area in 1958 and the Line of Actual Control (LAC) now runs nearly 20km west of Khurnak.

The Chinese are building the second bridge just a month after completing the first bridge, and it has set alarm bells ringing in India’s defence and strategic establishments. “Now, we will have to rework our contingency plans along with our offensive and defence strategies,” an on-scene commander told THE WEEK. India has been closely monitoring Chinese activity in Khurnak since January, but could not do much as the construction was happening within the territory under Chinese control. The first bridge, which was completed in April, is being used by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to transport construction equipment to build the second bridge. “The bridge gives the Chinese military an operational advantage. They have achieved a complementary approach to support both banks of the lake, thereby neutralising our tactical advantage,” said Lieutenant General Vinod Bhatia (retd), former director-general of military operations.

Latest satellite images show that the new bridge is bigger and wider—it is 450m long and 10m wide—and is meant for faster movement of not just troops and vehicles, but even tanks. It is expected to be ready by July. The bridge will cut the distance from Rudok—the PLA’s main base servicing its deployments in the Pangong area—to the LAC to about 50km, from the existing distance of over 200km.

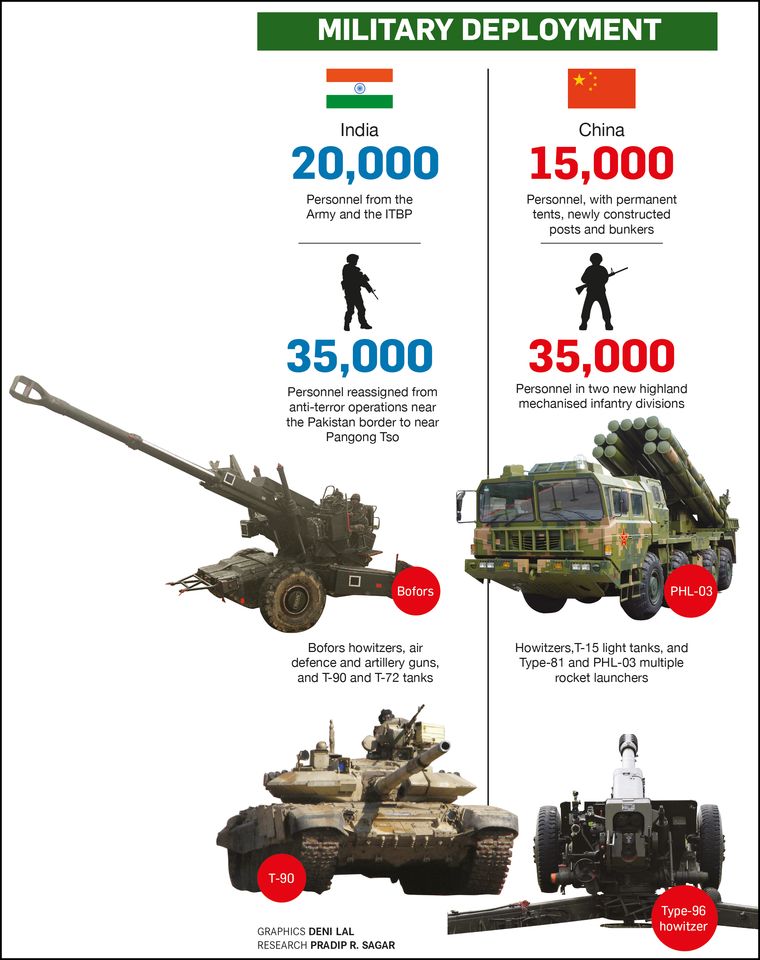

China’s strategic intent is clear: it plans to keep the positions it recently captured in the Pangong area. In May 2020, Indian and Chinese soldiers engaged in a brawl near Pangong Tso, causing serious injuries to both sides. A month later, a deadly clash in the Galwan valley resulted in the death of 20 Indian soldiers, including the commanding officer of 16 Bihar, Colonel Santosh Babu. It was the first time in nearly five decades that fatalities were reported on the LAC, and it triggered massive deployment of troops and heavy weapons by both armies.

“We now have a heavy, conventional deployment of troops. Earlier, there was only a thin deployment,” said Leh-based strategic expert and former ambassador P. Stobdan. “The dimensions have changed because of the highly intensified military deployment. Pangong has changed a lot. I believe our deployment is in response to China, which has enhanced its presence on the lake.” Both sides are engaged in building new roads, bridges, bases, airstrips and advanced landing bases.

Some military strategists, meanwhile, believe that the PLA is building the new bridge as a defensive action after it was caught off guard by the Indian Army’s Operation Snow Leopard following the Galwan clash. On the intervening night of August 29 and 30, 2020, India took control of several key heights lying vacant since 1962, including Rezang La, Black Top, Helmet Top, Gurung Hill, Gorkha Hill and Maggar Hill of the Kailash range, overlooking China’s Moldo garrison.

Colonel Sanjay Pande (retd), who commanded an artillery battalion in the Pangong Tso area, said the bridge would help China mobilise its forces quickly. “It makes sustenance of forces easier and gives the PLA tremendous logistical advantage,” said Pande. Colonel S. Dinny (retd), who commanded an infantry battalion at Pangong Tso, said that by building a bridge in a territory occupied illegally, China was asserting “sovereign rights” over Indian territory. In fact, back in 2017, India had plans to build a temporary bridge across the lake for swift mobilisation of troops. But, the plan did not take off. “We should have built the bridge. I am sure we will build one now. That would be enough to send a message to the PLA,” said Dinny. “We are already in the process of matching the infrastructure development, but since we started late, it will take some time to ensure parity with China.”

There is, however, not much India can do to deter the Chinese infrastructure upgrade on the territory under its control other than sticking to the diplomatic route. The only feasible response is to have reciprocal infrastructure development in areas controlled by India. For instance, despite strident Chinese opposition, India went ahead with building several bridges on the Shyok River and in Daulat Beg Oldi in the past couple of years.

On the strategic front, the confrontation between Indian and Chinese forces at Pangong Tso is largely on the eight spurs—called ‘Fingers’ in military parlance—jutting out of the Chang Chenmo range, an eastern extension of the Karakoram Range which ends at the north bank of Pangong Tso. Traditionally, India exerted control up to Finger 4 and has claimed up to Finger 8 from where the Indian perception of the LAC starts. India has a permanent position near Finger 3 (named after Major Dhan Singh Thapa who was awarded Param Vir Chakra after the 1962 war), while China maintains a base east of Finger 8. But over the years, China steadily encroached upon Indian territory. Both sides have now reached an agreement giving India control up to Finger 4 and the rest to China.

“Our silence for over 60 years on China’s illegal occupation of Aksai Chin has encouraged it to move further and encroach upon our territory. After digging in for the last two years by amassing troops and weaponry, the Chinese have now extended their reach for an offensive mission on the lake,” said Pande.

Until May 2020, Pangong Tso had only minimal military presence. Only one company each of the Army and the Indo-Tibetan Border Police were deployed in the area. Now, the entire lake is militarised. The PLA is converting its temporary ammunition dumps, helipads and surface-to-air missile positions into permanent ones. Its soldiers are equipped with howitzers, T-15 light tanks, and Type-81 assault rifles and PHL-03 multiple rocket launchers. The PLA has augmented its manpower by deploying two new divisions from the Xinjiang Military District, with elements of motorised infantry, armoured, artillery and anti-aircraft regiments.

On the Indian side, nearly 20,000 troops guard the region, armed with Bofors howitzers and BMP-2 infantry combat vehicles. Armoured columns of T-90 and T-72 tanks are stationed behind. Several news posts with additional deployment and bunkers have come up. A large number of additional battalions have been moved to Ladakh from the western sector. To patrol the lake, Indian Army’s new boats, capable of cruising at a speed of nearly 40kmph with around 20 soldiers, are deployed. Built by Goa Shipyard exclusively for the Army, these advanced boats can be modified to fit light weapons if needed.

The ITBP, the force responsible for guarding the India-China border, too, has made significant enhancements. It has deployed close to 40 per cent additional troops in the area. New border outposts are being created along with infrastructure development of barracks and accommodations for better living conditions, while existing outposts are being further strengthened with additional men and machines. ITBP director-general Sanjay Arora told THE WEEK that his force was ever vigilant at the border. “We have taken various measures to strengthen our infrastructure at all our areas of operations including the remotest and harshest environment,” he said.

Despite the improvements, the task of a commanding officer to get the best out of his men under hostile weather conditions continues to be daunting. Lieutenant General Rakesh Sharma (retd), former commander of the Leh-based 14 Corps which is in charge of eastern Ladakh, said because of the ongoing tensions with China, the level of vigilance required is high, putting soldiers under tremendous strain. “However, the first problem faced by a soldier in Pangong Tso is survival; fighting the enemy comes only next,” said Sharma. “It is so windy and cold that it saps your energy. People tend to lose their appetite and you need to force them to eat. Most people hesitate to take a bath, and ice has to be melted even to brush your teeth.” Moreover, there is no shade and the strong sunlight and ultraviolet rays pose severe health risks.

The Army follows a specific acclimatisation drill before deploying troops to Pangong Tso and other parts of eastern Ladakh, because low oxygen levels and harsh weather conditions can cause multiple physiological and psychological effects. Usually, the acclimatisation period is 11 days, done in three stages at different altitudes. But with changing security scenarios and large-scale deployment, the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) and the Directorate-General Armed Forces Medical Services (DGAFMS) are looking at cutting the acclimatisation period.

A colonel who commanded a battalion in the area, too, agreed that the weather posed a bigger challenge. “Winds generally start around noon and continue throughout thereafter,” he said. “Even in summer, chilly winds can cause injuries similar to burns. And in winters, with temperatures dropping to minus 20 degrees Celsius, soldiers face problems like frostbite, snow-blindness and hypoxia.”

Pande flagged food and nutrition as another major concern as the soldiers get only tinned, pre-cooked ration. “Even eggs come in powder form. Eating fresh vegetables is like a blessing,” he said. During the brief four months of summer, the Army dispatches about 100 trucks a day with rations, engineering and medical stores, weapons, ammunition and equipment, clothing and vehicles. There are about 80 items stocked for soldiers, including vast amounts of kerosene, diesel and petrol. Turnover of the troops is another issue, as keeping them on two-year tenures under harsh weather conditions is tough.

Keeping the growing concerns in mind, the quality of tents and special clothing has been improved. Procurement processes have been simplified and financial powers are delegated at all levels. Moreover, any requirement by the 14 Corps is taken as a priority by the Army HQ.

Another major problem confounding the security planners is that unlike most other hotspots along the LAC, Pangong Tso is also a popular tourist destination. Pangong Tso and its surroundings were opened up for visitors in the early 1990s, and it became famous after the climax of the 2008 Bollywood movie 3 Idiots, starring Aamir Khan, was filmed near the lake. Ironically, the movie was equally popular in China.

For tourists as well as soldiers, the only way to access Pangong Tso is by road. Once you start your ascent from Leh, oxygen levels go down steadily, causing nausea, shortness of breath and other problems associated with altitude sickness. Although the distance to the western tip of the lake is just around 140km, the journey involves crossing the formidable Chang La, a mountian pass situated at an altitude of 17,585ft (5,360m). The pass is said to be named after Sadhu Changla Baba, and there is a temple dedicated to him. Several Buddhist monasteries like Thiksey, Hemis and Shey can be found along the route.

A five-minute halt at Chang La offers a chance to have a cup of hot tea or coffee at a cafe run by the Ladakh tourism department. But the bone-chilling cold and the icy winds force most visitors back into their vehicles quickly. The descent from Chang La towards Tangtse and Durbuk is quite steep and the entire stretch looks barren, devoid of any flora and fauna.

Driving through Chang La is in itself arduous, and to make matters worse, the traffic comes to a standstill whenever a vehicle breaks down—a common occurrence on the route. Landslips, snowfall and boulders tumbling down the mountainsides add to the woes. Our driver, Dorjey Gyalson, said negotiating the stretch needed a great deal of skill and patience. “Moreover, you need to give way to military convoys which are quite frequent as the entire Pangong Tso sector is being serviced by this single road. Tonnes of supplies needed to maintain the troops at Pangong and Chushul sectors move through this road every day,” he said.

At Lukung, the place most frequented by visitors to Pangong Tso, multiple checkpoints put up by the Army and the ITBP convey the impression that things are not normal. Local people, meanwhile, appear worried about the rising security threat. Jigmat Spaldon, a nurse from Mann village, said Pangong Tso no longer remained the place it used to be. “Earlier, tourists used to come for its picturesque beauty, but now they are more inquisitive about the place where Indian and Chinese soldiers fought with each other,” he said.

Rigzen Motup, who runs a small tourist camp near the lake, was hopeful that tourist arrival could pick up once again after two years of the pandemic and the simmering military tension, but reports about China building a second bridge have come as a dampener. Motup, who represented the area in the Ladakh Hill Development Council (LHDC) for 20 years, said the growing military tensions were hurting the interests of the local people. “Nomads from our area used to go deep into the Finger 8 region with their yaks and goats in search of pastureland. But since May 2020, the situation has changed completely,” he said. Motup told THE WEEK about the Chinese incursion into Finger 4, which was well within Indian territory. “Over 500 PLA troops came on several boats. Our troops were taken aback and were completely outnumbered. We only had 70 odd men to counter them. Before reinforcements could come from our side, the Chinese took control of Finger 4.”

Local people find it difficult to trust the Chinese even as the diplomatic track is being worked upon to find a solution to the crisis. “Even in 1962, they attacked us after the disengagement agreement. We are still scared,” said Motup. Tsering Angchok, who is from the neighbouring Merak village, still remembers the 1962 war. “I was only 24 then and was part of a group of locals who supplied drinking water to Indian troops. I could see similar hostility between the two armies now, especially after the May 2020 standoff,” he said.

The ongoing tension could lead to the economic ruin of these border villages. Tsering Angdus, the pradhan of Merak, said the entire village depended on their yaks and sheep for survival, but the volatile situation had robbed them of their grazing land. “The Army no longer permits us to move beyond our village. Earlier we used to cross the lake with our animals. Now multiple posts and bunkers have come up. Some of us now work with the Army as porters to transport essential goods and weapons,” he said.

Next to Merak is Kakstet, the last village controlled by India in the region. The village has no mobile network and power supply is for just eight hours a day. In fact, of 236 habitable villages in Ladakh, only 172 have telecommunication infrastructure; just 24 and 78 villages have 3G and 4G internet connectivity, respectively. Konchok Stazin, who represents Chushul in the LHDC, said while the Indian villages lacked proper communication facilities, China is carrying out a massive infrastructure upgrade on its side of the LAC. “After completing the first bridge over Pangong Tso, China installed three mobile towers quite close to Indian territory,” he said. Stazin met Defence Minister Rajnath Singh last November and apprised him of the situation and pitched for strong border infrastructure, modern amenities, mobile connectivity and universal internet coverage.

Stazin pointed out that China gave its nomads unfettered access to the border areas and also the freedom to move around as they pleased. “China uses its nomadic community to encroach on our land in an effort to claim more territory,” he said. “Sadly, our nomads are restricted by our own security forces from grazing their livestock on their traditional pastures. I strongly feel that our nomads are soldiers without uniforms. The Indian Army must trust them by not restricting their movement.”