IIf there is one source of inspiration that keeps Chetan Sakariya going, it is Usain Bolt’s autobiography Faster than Lightning. The sprinter from Jamaica started out poor in life, made giant strides and ended his career as the fastest man alive. Oh, and he also became a global icon. Chetan, 24, has lived through that first part, and is working on realising the rest.

In the book, Bolt writes about being consumed with a different level of energy when at the Olympics. “It had to do with that big, world-stage phenomenon. That is exactly how I feel, too,” the Delhi Capitals’ medium-fast bowler tells THE WEEK. “As if I was born for the world stage with the crowd cheering me on. It motivates me a lot. The moment I hit the ground, I become calmer and feel energy in a different way.”

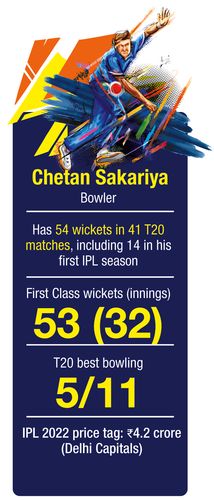

Though both his IPL seasons were played under the spectre of the virus, which meant no full stadiums, Chetan always felt like the eyes of the world were on him. And though he only got three chances this season, he did dismiss a raging Jos Buttler cheaply. His 2/23 helped DC win that match. In the previous, he took 14 wickets in as many matches for Rajasthan Royals.

Now out of the bio-bubble, he also wants to leave the cricket bubble. Bungee jumping in New Zealand is next on the agenda. “When you have the money, you start making a bucket list,” he says, his eyes bright. Chetan was a net bowler for Royal Challengers Bangalore before Rajasthan Royals signed him in 2021 for Rs1.2 crore. He went for Rs4.2 crore the next year.

For a family with a monthly income that seldom crossed a few thousand rupees, that auction paddle was a life raft. “Yes, I do feel great because all of a sudden life took a turn for the better,” he says. “I’m quite settled. Right from the day I won the Ranji Trophy [with Saurashtra] to the day I made it to my maiden IPL season to my debut for India in Sri Lanka, it all happened in such a short span that I really did not have the luxury to soak it all in.”

To those who know him, Chetan’s story is of a lotus blooming in the mud. “His parents used to work in a brick kiln, earning barely enough to run a household of five,” says his maternal uncle Kalubhai Jambucha, who took up Chetan’s responsibility when he was a toddler. The family is from Vartej, a town about three hours south of Ahmedabad. “Most of the time they would be living outside the kilns and would hardly be home,” he says. “His father could not work much because he would be sick most of the time—his legs hurt because of frequent operations resulting from accidents. His mother would do odd jobs to make ends meet.”

As the eldest among three children, Chetan also had to be a provider. His father later started driving a van on rent to transport goods, but was out of work at times. “One day, Chetan told me that, no matter what the situation, he would not leave cricket. ‘You can burden me with responsibilities and I’ll handle them. But I will continue to play my game,’ he said. ‘And I will prove to you that something will definitely come out of this’,” says Jambucha.

Chetan began helping his uncle for four hours a day at the latter’s stationery distribution business. “Had there been anyone else his age, it would have taken 10 hours to do the exact same work he did in four,” says the proud uncle. “Such was his dedication to cricket that he made time for it no matter how challenging it was.” In return, Jambucha took care of his nephew’s every need.

He remembers Chetan being a “very strong” boy. “As a kid he would drink a litre of milk in one go,” he says. “We used to call him ‘Tarbooz’ (watermelon) out of love. He was that plump and healthy.”

Chetan was also excellent at studies and was curious by nature. However, he gave up on textbooks after class 12 to focus entirely on cricket. Jambucha was not convinced. His Gujarati business mindset only allowed the boy two years to prove his mettle. If he failed, he would manage the business.

Chetan had played for his school team till then and had been selected for the Saurashtra U16 team. But injuries kept interfering with his ascent. “Injuries in my lower back and groin really made it difficult for me to return to form,” he says. “Pain and mental exhaustion were consuming me. There was a double quandary—no studies and no cricket. I was 19. Because I wanted immediate success, I began taking too much load and injuring myself.”

Also read

- Streets to suites: Rags-to-riches stories are becoming more frequent with every IPL

- The only one I have to prove anything to is myself: Yashasvi Jaiswal

- My boss used to mistreat me; he now calls me sahab: Rinku Singh's father

- I have given all my money to dad and told him to keep me away from it: Tilak Varma

- I had anxiety attacks and was prescribed sleeping pills: Kuldeep Sen

- My dad asked me why I was giving up volleyball: Kumar Kartikeya

That was also the time he went into his shell, says his coach Satyajitsinh Gohil, who also became his best friend and mentor. “He went off the map,” says Satyajitsinh. “His sabbatical had extended to over a year. We then had to convince the family to encourage him to get back. And when he did return, he bounced back in style. He made it to the U23 team and went on to excel in the Ranji trophy (both for Saurashtra). He has great resilience.”

Today, as he busies himself making bucket lists, Chetan recalls a time when he could not afford a cricket kit; it was called a “rich man’s indulgence”. “We were taught to save money for medical emergencies and weddings. Not for time-pass like cricket,” he says. “I did not even have good shoes, but never gathered enough courage to ask.”

In 2020, he was on the cusp of getting an IPL contract and changing his life. But then, tragedy struck. His brother, who was just a year younger, died by suicide. Soon after, he lost his father to Covid-19. “Financial and family struggles have been a significant aspect of my life,” he says. “But, in a way, they also turned into my biggest strengths. I began focusing more on cricket only after my brother’s demise. And now that I have lost both of them, I have realised how enormously important it is to express one’s love.”

His sister, Jigna, got married recently and he made it a point to attend. However, he is extremely selective about attending events or meeting friends. “His friend circle is extremely limited. He is focused and does not even attend family functions unless he is obliged to out of courtesy,” says Jambucha, who was disappointed that Chetan did not come for his birthday.

With the last IPL earnings, Chetan bought a house in Rajkot and a car. His dreams have been fulfilled, for now, and it is now time to “live it up”. In the past two years of being cooped up inside bubbles, he has read a lot, mostly autobiographies, and has become more conscious of his diet and fitness. “No more sweets. No more junk. And no more of the desi accent,” he says. “I think five to six years of being away from home and meeting people from different cultures does that to you.” Any girlfriends? “Yes,” he says, blushing. “The difference is that I have begun to live my life more. Earlier, it was about savings and survival, now it is about travel and enjoyment. I have learnt that life is unpredictable and unfair. Anything can happen at any time. Now, I try to live as much as I can. Earlier, I used to do a lot for my family and for relatives. But now I give all my time to myself.”

He does, however, try to spend as much time with his mother as possible. “My mother loves to go to temples,” he says, “and I have a bucket list for her, too.”