Avegetarian who loves 'regular' south Indian fare, Tata Sons chairman N. Chandrasekaran is not particularly known to be a gourmet. Yet, one of the first steps he initiated after Tata bought back Air India was to jazz up the inflight food.

Out went Air India's four-year-old ban on non-vegetarian food in domestic economy. The airline rolled out an enhanced meal service on the Delhi-Mumbai trunk route, followed by the rest. Caterers and flight kitchens were briefed and the fully-loaded meal tray came complete with an appetiser, a piping hot main course (veg or non-veg), followed by dessert, tea and coffee. Cabin crew are said to be undergoing refresher courses on table setting of multi-course meals. A circular in January brought back melamine and porcelain cups for tea/coffee, and highball glasses and wine goblets for beverages. Goodbye, plastic and styrofoam!

“The food and the service were better. The ground staff were courteous,” said Delhi-based lawyer Divya Nair, who recently took an Air India domestic flight. “But then, the seats were dirty and rickety. The cabin looked shabby.”

Chandrasekaran knows a lot more needs to be done. “The task is huge... but we have the entire nation wanting us to succeed,” he said in an address to employees after Tata formally took over the national carrier. “This will require a huge transformation, probably the largest transformation you would ever go through.”

Even mega transformations have to start with small steps. For Air India, that was by improving meals and sprucing up the customer interface. Particular attention is given to customer-facing employees, with monitors reportedly assessing them on a quarterly basis. On-time performance (OTP) was another criterion. Pilots must close cabin doors ten minutes before departure time. It has, apparently, helped. Air India's OTP shot up from 71 per cent to 91 per cent after Tata took over.

There is a reason why Chandra, who has an empire of 30 companies to run, is playing the god of small things. He and the incoming CEO Campbell Wilson have the unenviable task of turning around a white elephant run to ground by decades of bureaucratic malfeasance. Despite the government hiving off a large part of Air India’s debt before the selling-off, the Tatas have still been saddled with Rs15,300 crore of debt; not to forget the fact that the airline was bleeding Rs20 crore every day when it was sold.

Chandra’s plans include changing the organisational structure of the company. Executives from group companies like Tata Consultancy Services and Vistara have been brought in to make it more nimble. A massive digitisation process is on. The mobile app and website are to be overhauled, and Amadeus replaced Sita as its reservations backend provider recently. He is painfully aware that it is going to be a long haul. “There are lots of issues that need heavy lifting. There is no magic wand,” he said in an interview to a newspaper. “It won’t happen overnight, but we are on the job.”

The parent company has allocated Rs15,000 crore in equity to Air India, and there is more coming. A voluntary retirement scheme has also been offered to 12,000 plus employees (employees above the age of 40 are eligible for this), even as a recruitment drive to infuse fresh blood has been set in motion. “In the next 12-24 months, there will be visible progress,” Chandra said.

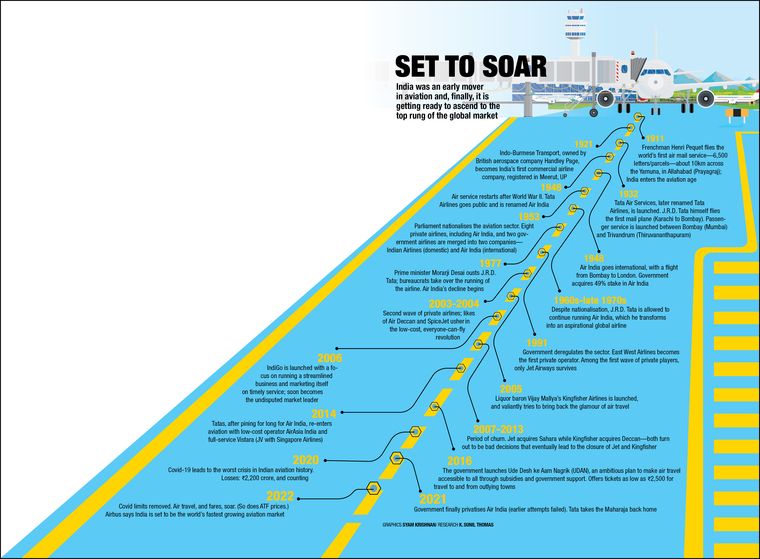

It augurs well, then, that the next 12-24 months could also see a renaissance in Indian skies. Covid willing, air travel is set for an unparalleled boom that could well see India not just becoming the fastest growing aviation market, but one of the three biggest in the world.

Two new airlines are set to take to the skies, while a massive investment spree in airport infrastructure could see several new airports coming up and many existing ones getting a facelift. And the government’s UDAN scheme’s new phases of expansion could take air travel further to the masses, aiming at a conversion of train travellers into flight passengers as more small towns get on to the air map.

“Just look at the growth potential,” said Civil Aviation Minister Jyotiraditya Scindia. “Presently you have 14 crore flyers a year out of a population of 140 crore. That means the penetration rate is just 10 per cent. The number I am looking at is 40 crore in the next four to five years!”

Quite ironic, considering that just two years ago, the aviation sector had run into its worst crisis. Even before Prime Minister Narendra Modi imposed a national lockdown on the night of March 24, 2020, to tackle the pandemic, the skies over India had emptied out. While air traffic was restarted in bits and spurts two months later, there were new challenges like restrictions on fares and cumbersome Covid safety protocols.

Worse, the down-in-the-dumps sector was left high and dry through the many tranches of stimulus packages announced by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman to revive the economy.

Through this pandemic glum, however, there was a sliver of light. “The demand for air travel has strengthened over the last two years. The impact of the Covid waves on passenger traffic has gradually been decreasing,” said Indigo’s CEO Ronojoy Dutta.

As the government finally relaxed all restrictions on international travel in the last week of March, it was like the floodgates had opened. Call it revenge travel or the summer rush, a surge in demand for travel through May, June and July has seen airfares soaring sky-high. Travel agents say that fares to the US and Canada have shot up by up to 90 per cent. A European vacation for an Indian family this summer costs two times what it did before Covid.

According to the travel portal ixigo, one-way fares on the Delhi-Mumbai route were up 37 per cent in May compared with the beginning of this year, while Bengaluru to other metros were up 37 to 27 per cent. Underserved routes were higher by nearly 50 per cent. “We are seeing a strong desire for grand getaways fuelled by pent-up demand and limited travel options for the last two years,” said Aloke Bajpai, group CEO & co-founder, ixigo. “We recently surpassed pre-Covid levels of domestic passengers a day, which is a very good sign. Overall travel sentiment for domestic and international travel is at an all-time high.”

And things can only get better. Or at least, that is the sentiment. While Air India is undergoing the makeover of its life, fellow brands in the Tata kitty are not exactly sitting it out. AirAsia India, in which Tata now holds 83.67 per cent, is set to be merged with Air India Express, which primarily links Indian cities to the Middle East. The combined AirAsia India-AI Express entity reportedly has plans to not just start services to tier 2 and tier 3 cities in India, but also spread its wings to 30 countries across the continent, from Turkey to China to the Philippines.

As for Vistara, the fourth carrier in the Tata fold, major expansions on domestic and international routes are being planned, even though the question of a merger with Air India is left hanging in the air. When asked, Vistara's chief commercial officer Deepak Rajawat said: “Vistara continues to operate as an independent airline and both our parent companies remain invested in our growth and expansion journey ahead.” What decision Singapore Airlines, Tata’s partner in Vistara, will take—whether to come on board with a deeper collaborative partnership in a combined entity or to sell its stakes and leave—will be crucial in its future.

While Vistara has great branding, it goes without saying that seasoned air travellers in the country still hark back to the glamorous days of Jet Airways and Kingfisher Airlines. The KF fizz has gone flat, but Jet could still have a second coming. The first asset reconstruction plan of an airline under India’s bankruptcy laws could see Jet taking to the skies under its new owners, the Jalan-Kalrock Consortium. The airline has got all approvals from the regulator, though a date of commencement of operations is yet to be announced.

“Jet in its new avatar is a new airline except for the name,” said Sidharath Kapur, aviation expert and former chief of the airports businesses of GMR and Adani. “It is a fresh haul for them. Eventually their success will depend on the capability of their financial backers. This is a business that needs deep pockets.”

The other new entrant, Akasa, is the brainchild of ‘big bull’ Rakesh Jhunjhunwala, who is positioning it as a low-cost carrier. The airline has already made a splash by ordering 72 Boeing 737 MAX aircraft and unveiling a bold orange livery on social media. Though it was supposed to start operations in June, delay in delivery of the first plane has cost it a few weeks.

“Jhunjhunwala can bring in funds for at least the first few years, which is the most challenging period for any new airline,” said Kapur. “In the airline business, there are periods of growth and long periods of losses. You have to recoup your losses when the times are good. I am sure a good period is coming in terms of traffic, so the new players will have an advantage.”

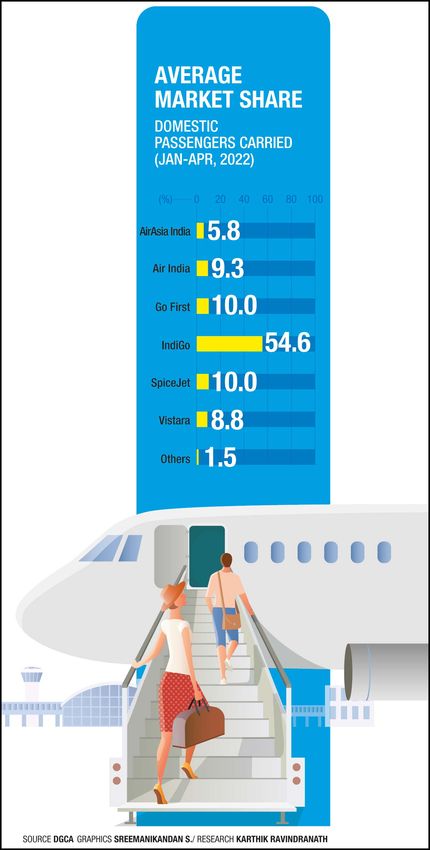

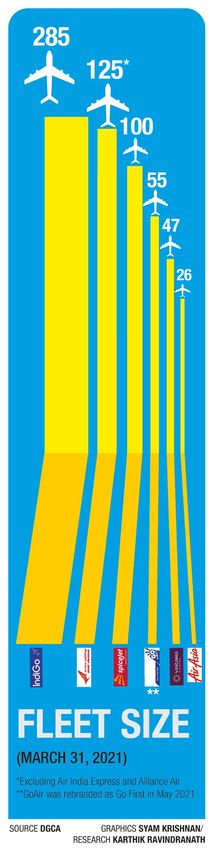

While boom times may be ahead, the presence of a market leader that has become a behemoth muddles the scenario. IndiGo, which came out of nowhere in the late 2000s with its formula of ‘on time, every time’ now straddles India’s airline industry with a market share of nearly 60 per cent. The cash-rich Gurgaon-based airline is now muscling up to protect its domain from the new upstarts as well as the resurgent Tata brands. “As the market leader, IndiGo would want to protect its market share," said Jagannarayan Padmanabhan, director and practice leader (transport and logistics), CRISIL. “IndiGo’s stated objective is to expand its footprint into tier 2 cities and cargo. It would continue to maintain a value-for-money proposition to the end-customer, and that would reflect in ticket prices.”

Padmanabhan said that if two players (Indigo and Tata) held more than 80 per cent of the market between them, they had significant pricing power. “The most optimum airline then would be the one that can operate at the least cost and [still] make money. In such a situation, smaller airlines will be at a disadvantage,” he said.

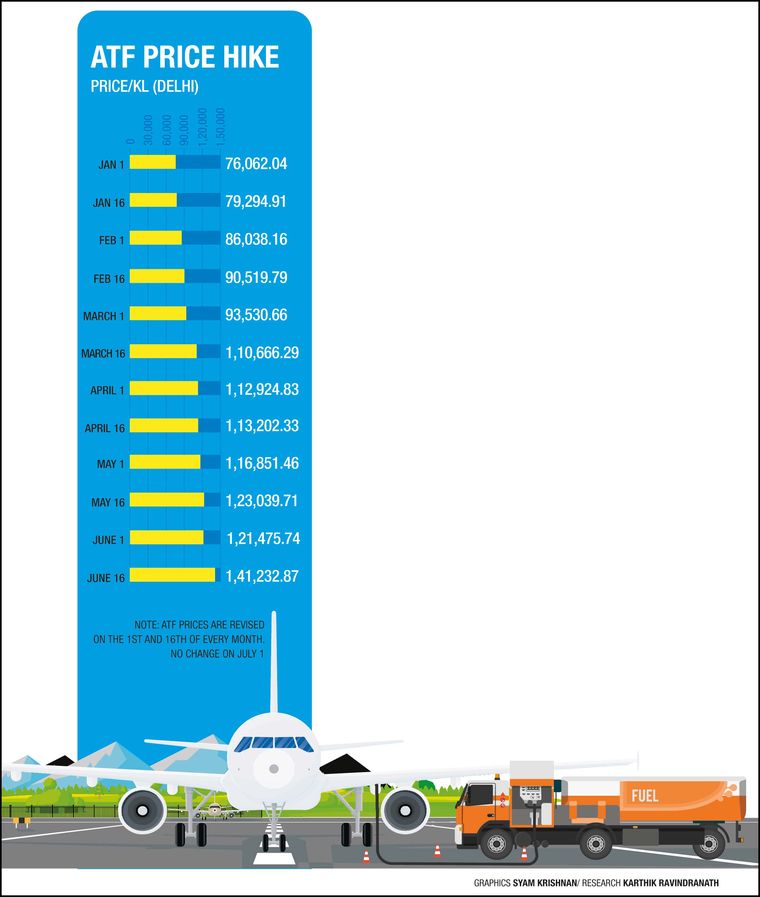

How aggressive Indigo would go to undercut new challengers is open-ended, considering the rise of aviation’s bogeyman—fuel prices. Aviation turbine fuel (ATF) prices went up nine times this year, rising from Rs72,000 a kilo litre to Rs1.23 lakh in May. That is a rise of 61 per cent in just five months, a proposition made worse by the decline in the value of the rupee. And, when you consider that fuel is the biggest cost in operating an airline, at around 40 per cent, you realise that it is enough to upset the best-laid plans.

“ATF prices definitely come as a significant hurdle in the recovery of the industry,” said Rajawat. “While the authorities have supported by reducing VAT on ATF in many states, there is still a long way to go to make it more viable for airlines.”

Airlines expect more measures. “The government can play a role in balancing out the taxes, maybe subsidising aviation for the time being,” said Poonam Verma, partner at J. Sagar Associates. “There is an impression that air travel is a luxury. It is not. We need to reach a point where air travel is comparable with rail.”

The finance ministry, which would rather have ATF under the goods and services tax, has been dragging its feet on a proposal from the civil aviation ministry for import duty cuts, considering that 85 per cent of the fuel is imported. Though many states slashed VAT on ATF, it has not had the desired impact, as the opposition-ruled states that house three of the busiest airports in the country—Delhi, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal—are yet to do so.

How are the airlines managing? By the skin of their teeth, it seems. Many are putting their Covid lessons to use, trying to slash costs wherever possible. “We have taken several measures to reduce non-customer facing operating expenditures while making every effort to conserve cash,” said Rajawat. “We renegotiated various contracts with partners, vendors, and lessors to reduce cost while also exploring newer avenues to supplement our earnings.” For Vistara, this has included charter flights as well as ancillary services like upgrades and Purple Ticket Gift Cards. SpiceJet, for all its financial woes, has been doing well with its cargo business. Go First, the new branding of Go Air, plans to go for an IPO next month to fund its operations.

But there is a reason despite all the present imperfect tense the airlines are waiting for a fast forward future. “Indian aviation can only grow. Right now, just consolidate, protect, wait and watch,” said Padmanabhan.

The boom could well be on its way, with an under-penetrated market itching to switch from trains to planes, and airport operators expanding their footprints into smaller towns. “With India expected to have 200 airports by 2026 (from the present 140), tier 2 and tier 3 cities are expected to be the forerunners in the growth of the aviation sector in India,” said a spokesperson for the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj International Airport in Mumbai, run by the Adani group.

“India’s aviation industry needs to restructure and refocus from business travel, which is unlikely to come back soon,” said Sangita Dasgupta, associate professor, School of Management, BML Munjal University, Haryana. “Deep penetration into small towns, increasing connectivity and keeping prices reasonable can help in overall inclusive development.”

There is no doubt that the new entrants and the increasing competition are a positive factor for customers. “If airlines are ready to possibly offer more parity as far as rail travel is concerned, then you are going to see a significant shift,” said Kapur.

And, probably, the authorities and the airlines should focus on what matters. “You don’t need fancy airport terminals or food courts or big planes,” said Padmanabhan. “Those travelling by train are the sort of people you can get to fly if the pricing is right. It is possible if you have lower price points, less overheads, better capex, better engineering and better mileage—by optimising the whole mathematics of flying.” If that happens, maybe even sky is not the limit.