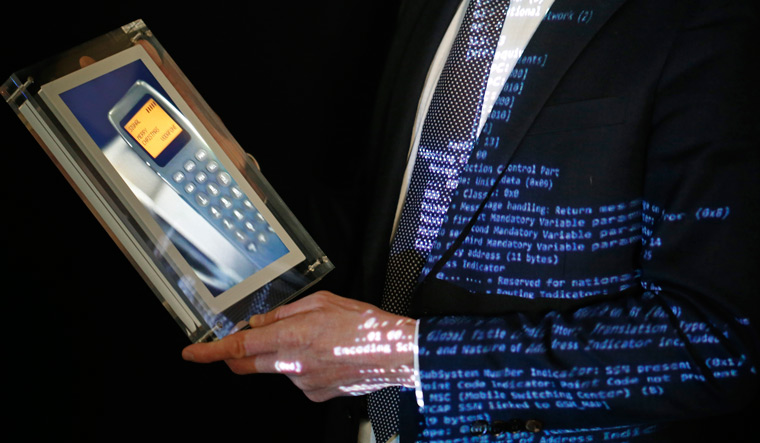

For centuries, Christmas had been an occasion to be celebrated among friends and family in close proximity. Santa Clauses and stockings filled with presents—both mythical—stories of red-nosed reindeer and relatives singing largely off-key versions of ‘Deck the Halls’ were all privileges to be enjoyed (or suffered) under one roof. Until Neil Papworth, a 22-year-old software programmer from the UK, arrived on the scene in 1992. Heroically, he sent the first-ever text message—“Merry Christmas”—to his colleague Richard Jarvis, who received it on his four-pound Orbitel cordless telephone. A year later, Nokia introduced the SMS feature on its handsets. Like long-range ballistic missiles, Christmas messages exploded across the world, distance no longer a bar.

At first, text messages had a 160-character limit, which propelled the birth of ‘txt spk’, signified by the world domination of abbreviated phrases such as LOL and ROFL. Christmas might have gotten truncated to X-mas, but it still remained as expensive as ever, especially that first Christmas message, which was sold as a non-fungible token for £90,000 to an anonymous buyer last year.

Thirty years after the first message, text has been dethroned as a medium of communication. Today, SMS is only good for receiving spam messages and OTPs for online purchases that you invariably end up regretting. Even in the larger context, we are moving into a post-text world online that is dominated by videos, memes, GIFs and reels. A world that is saturated with visual and auditory stimuli—from the glut of Instagram images to the ding of an incoming message or an email alert on your phone. You never realise the addictive power of that ‘ding’ more than when you itch for a red light while driving to check the message. Internet royalty used to be mostly concerned with text-based blogs and web pages; now it is podcasts, videos, memes and reels.

This shift from text to multimedia has left its imprint on every aspect of our online lives. Take, for example, ed-tech. “Ed-tech has moved hugely from the traditional text-based approach to videos and other multimedia formats,” says Jibin C. Joseph, head, digital strategy at Virallens Advertising, who has been working in ed-tech for many years. “But this does not mean that all teachers are happy with this change. Their argument is that the traditional methods of teaching aid in visualising, while videos don’t do that. Take, for example, learning the concept of inertia in physics. You could teach that through a video of children travelling in a bus. When the bus stops, the children move forward. But for students to make that application of inertia across multiple functions, they need to visualise. Otherwise, they will be stuck to that one bus example.”

Joseph says that the shift from text to multimedia primarily took place in India when data became cheaper. Otherwise, it was restricted to those who had broadband at home, which was the wealthier sections of society. To access multimedia you needed a good internet connection. But when Jio started selling data cheap, multimedia exploded. There was a further spike in usage during the pandemic.

There are other behavioural changes, too, that this shift is triggering. It could, for example, promote a culture that prizes emotion over logic. Catchy slogans and short memes play to our sensibilities more than to our sense. The well-argued long-form piece is facing the noose. “For the digital advertiser, these new modes of communication provide a great platform to create subliminal messaging that promotes brand recall,” says Narayan Rajan, CEO of iVista, a digital solutions provider. “For example, I could just bombard you with the message that THE WEEK is India’s number one magazine. You are only picking up that one line. You don’t know where you saw it. If you saw an Amul hoarding at a particular place, you would remember where you saw it and what it said. That is not the case here. This is way more effective and much cheaper. People start believing the message without looking at the facts. Nobody is verifying it.”

This kind of digital advertising also shortens our attention span. A catchy logo or brand name is designed to “prod the would-be attender ever onward from one monetisable object to the next,” writes Justin E.H. Smith in his book, The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is.

But hold on a second. It might not yet be time to write a eulogy for the humble text message. According to new research, reaching out to people in our social circles through a text or an email might be more appreciated by the receiver than we think. “Across a series of preregistered experiments, we document a robust underestimation of how much people appreciated being reached out to,” stated the study published in the American Psychological Association’s Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. According to psychologist and author Marisa Franco, we keep from contacting friends and family because of the ‘liking gap’, or “the tendency to underestimate how well-liked we really are”. So, pick up your phone and text a loved one. Don’t wait for it to buzz. Be the ‘dinger’ rather than the ‘dingee’.