In July 2017, a few weeks after the start of the confrontation in Doklam near the India-China-Bhutan trijunction, Lieutenant General Zhang Xuejie, the then political commissar of the Tibet Military Region (TMD) went to an ‘undisclosed place on the border’(probably north of Sikkim) and wrote in red letters “1962” on a stone. What message did he want to convey? That China could repeat the operations of 1962?

A month later, as the confrontation had entered its third month and as Delhi was not showing any sign of backing off from its intention to stop the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) from building a road in a disputed area, the Chinese media counter-attacked.

The Communist Party’s mouthpiece, The Global Times, warned, “The border standoff has stretched out for nearly two months. If the Narendra Modi government continues ignoring the warning coming from a situation spiralling out of control, countermeasures from China will be unavoidable.”

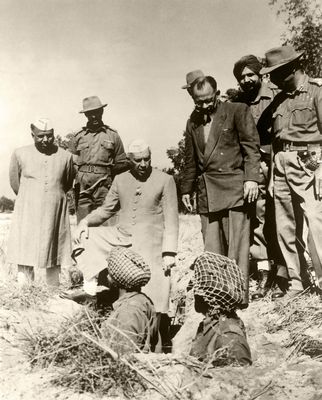

The newspaper then mentioned the 1962 war: “India made constant provocations at the China-India border in 1962. The government of Jawaharlal Nehru at that time firmly believed China would not strike back.…However, the Nehru government underestimated the determination of the Chinese government to safeguard China’s territorial integrity even as the country was mired in both domestic and diplomatic woes,” the newspaper cautioned. Beijing was probably still dreaming of repeating the 1962 ‘victory’, not realising that India and the world have changed since then.

Interestingly, after the Galwan clash on June 15, 2020 (it was Xi Jinping’s birthday), during which China is said to have lost some 40 of its soldiers—including a commanding officer—the Chinese media was quieter. Beijing had started realising that India would not be bullied so easily. This raises an obvious question: Can China play a redo of 1962 on India, or putting it differently, has India learnt the lessons of 1962?

It is necessary to first point out that the Sino-Indian border war was not a debacle as depicted by Beijing and some foreign commentators. India fought extremely well during the battles of Walong or Rezang La and in several other areas on the front, where hundreds of PLA troops were killed by Indian soldiers. Has Xi, the chairman of the Central Military Commission, heard of these battles? This part of the story was never told to the Chinese people. Similarly, what happened in 1967 when the PLA was forced to back out after having intruded into Indian territory in Sikkim, remains a state secret in the Middle Kingdom. Beijing, presently working on publications about China’s ‘victory’, would like India to still remember 1962.

The Chinese narrative remains the same: India attacked China. “Chinese military researchers have compiled a new history of the war reassessing its significance and legacy, bringing the spotlight back to the war amid the current tensions in relations,” wrote an Indian newspaper. One of the persons behind the ‘new history’ is Zhang Xiaokang, the daughter of General Zhang Guohua, who commanded the Tibet Military Command and directed the Chinese offensive against India in the eastern sector in October 1962. Her book is titled One Hundred Questions on the China-India Border Self-defence Counterattack. Extracts published on a Chinese website show that Beijing continues to propagate the myth that Mao Zedong had no other choice but to ‘counter-attack’.

The history of 1962 needs to be rewritten, and India should not be ashamed of its Army during those fateful months. On the contrary, it is time to do more research into those battles, build more memorials and museums and let the general public (and China) know about the outstanding valour of Indian soldiers.

Undoubtedly, with better political management and the use of the Indian Air Force (IAF) in particular, the war could have had a different ending. But let us look at what went wrong. First and foremost, the political leadership erred by not using the IAF. Wing Commander Jag Mohan Nath (retd), the first officer to have been decorated with the Maha Vir Chakra twice, had been on regular missions over Tibet for more than two years from 1960 to reconnoitre the Chinese build-up on the Tibetan plateau. He concluded that China had no air force on the Tibetan plateau. Unfortunately, the political leadership refused to believe the hard evidence gathered during his sorties.

Had the IAF been used, one can imagine that the casualties would have been less on the Indian side and more on the Chinese side; the Line of Actual Control would have remained where it was in September 1959 and the border dispute with China would not be so acute today; the Shaksgam valley would not have been offered to China by Pakistan in 1963; Mao would have lost his job and Sino-Indian relations would have been completely different.

It is certainly the most important lesson that India learnt from the war. Today after the induction of the 36 Rafale fighter aircraft, the IAF is ready to take on China and even has an edge due to the terrain as well as the preparedness, professionalism and experience of Indian pilots.

India has also far better knowledge of the border; let us not forget that the 7 Brigade was fighting in the Namkha Chu (river) sector, north of Tawang, without maps; weaponry was antediluvian and the arrogant political leadership would not allow local commanders to move to better strategic positions to defend their territory.

More recently, as the Doklam and the eastern Ladakh confrontations have demonstrated, the commanders have far greater autonomy. The present government has also delegated the negotiations about the disengagement on the border to the 14 Corps commander based in Leh.

With its in-depth knowledge of the terrain, the Indian Army has been able not only to hold onto its positions (though China still refuses to fully disengage from some places), but also could establish a far better synergy with the ministry of external affairs and other stakeholders; something totally lacking in 1962. Though it has delegated tactical decisions to local commanders, the political leadership is far more aware of the situation on the ground.

On their part, after 16 rounds of talks, the PLA generals have probably realised that India in 2022 is not the same as in 1962. Officers from both sides have learnt to know each other; they understand the other’s mindset and motivations better. One should add that the political leadership meets far more frequently than Mao and Nehru did, which is a good thing. A better understanding of India’s principled and firm stand could hopefully act as a deterrent for China.

Further, senior generals in the Indian Army, Air and Naval headquarters are more professional and are ready to make their voices heard. It was certainly not the case in 1962, when a chief of air staff did not even dare to try to convince his political masters to use the IAF, despite the full knowledge that China had no air force on the plateau and even lacked the necessary fuel supply.

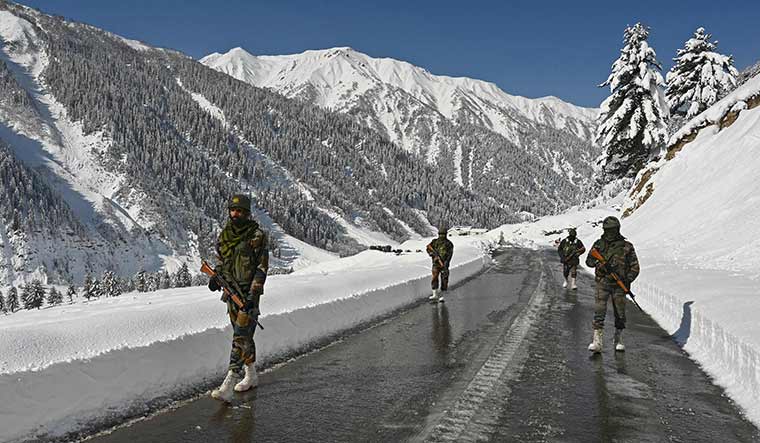

Sixty years later, the infrastructure on the Indian side has tremendously improved (on the Chinese side, too); there was a time when an argument was heard on the borders, particularly in Arunachal Pradesh: “It is better not to build roads on our side, otherwise they can be used by the Chinese invading troops once again”.

During the last few years, though the PLA has always kept a superior edge in infrastructure (the terrain is also easier on the plateau), Delhi has been working hard to reach each and every corner of the LAC.

One important factor in the ‘defeat’ in 1962 was the failure of the Indian intelligence. The intelligence inputs were probably there (through Wing Commander Nath’s secret flights or regular reports of the Indian consul general in Lhasa, the Indian trade agents in Yatung, Gyantse and Gartok, and also the Tibetan refugees in India), but they were not properly analysed by the intelligence bosses, who were too busy obeying the ‘ideological’ orders of their masters; this was particularly true for the director of the Intelligence Bureau who had been in office for too long.

Another important factor which may force China to think twice before embarking on a new 1962 is the Tibetan population living in India and particularly on the border. They are emotionally and physically supporting India. The role of the Special Frontier Force, composed of Tibetan commandos during August 2020 on the Kailash range, south of the Pangong Tso, is a case in point. The Tibetan populations on the plateau are also aware that their countrymen in India are allowed to practise their own faith and freely follow their leader, the Dalai Lama; it is not the case north of the McMahon Line. In case of a long conflict, it could be a determining factor.

Finally, the Ukraine war has demonstrated that it is not easy to win a short ‘local’ war, like China had hoped to do. Even if Beijing has the advantage in many domains compared with India (theaterisation of defence forces, infrastructure, use of artificial intelligence, drones), there is no way China can ‘teach a lesson’ to India today.

Finally, the post pandemic world is much more aware of China’s totalitarian side. In case of a conflict, this would translate into better real-time intelligence sharing and support. Xi was probably briefed of all these changes when he recently visited Xinjiang and met the top brass of the Western Theatre Command and the Xinjiang Military District.

But if China becomes desperate, due to an economic collapse for example, adventurism could be a way out for the totalitarian regime. Though India has learned many lessons, it should remain aware of these dangers; especially knowing tomorrow’s war(s) may be ‘unrestricted’, fought on multiple new fronts simultaneously.

—Arpi is an author, journalist, historian and Tibetologist.