It is a misty November morning. Our car exits National Highway 44 and rolls down sleepy village roads. The district is Haryana’s Panipat; the destination, Khandra village. On the way, we pass some village elders and teens, wrapped in shawls, rubbing their hands together, soaking in the winter sun. About 12km later, steered by Google Maps, we reach the house. Khandra looks like any north-Indian village―large green fields, a blanket of haze, narrow pucca roads and modest abodes.

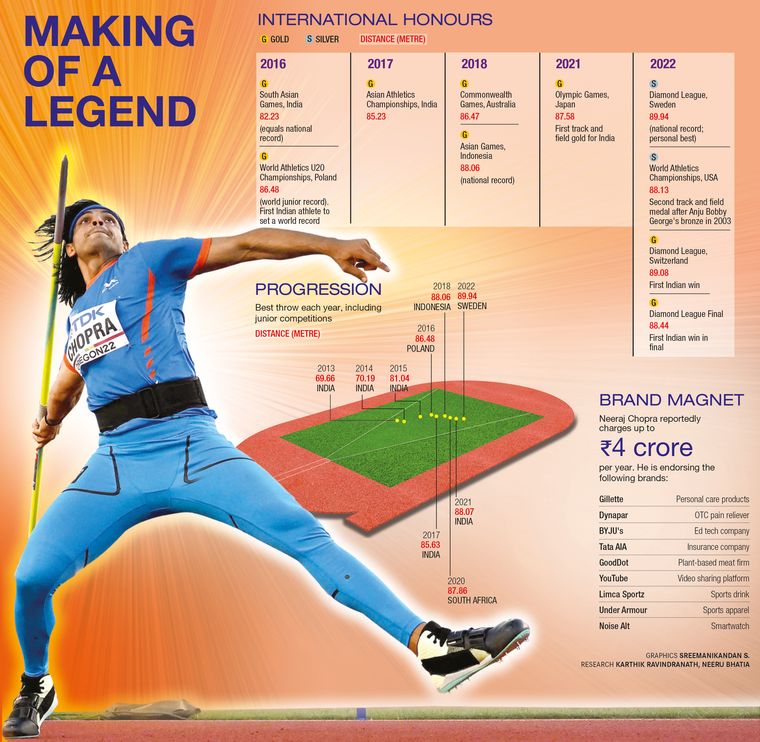

The house in question, however, sticks out. A modern bungalow with a massive gate, it looks like a place dust and grime would fear to sully. The brown-tiled, two-storey house dwarfs all the others in the area. Its resident, too, has done the same with javelin in hand. Only 24, Neeraj Chopra has won India’s only Olympics gold in athletics, is the only Indian to win a Diamond League final, and is on the shortlist to be the country’s greatest athlete. Sports fans of a certain vintage might argue that he cannot be spoken of in the same breath as a Milkha Singh or Dhyan Chand’s men, but it is a fact that Neeraj―in six years at the senior level―has scaled peaks no Indian has (see graphics).

A boy opens the gate and Satish Kumar, Neeraj’s father, watches keenly as we step out of the car. He has decided to forgo the fields for the day to welcome us. The rest of his siblings―Bhim, Surinder and Sultan―are out for work. The children are in school and college, the ladies busy in the kitchen.

Neeraj is absent, too. Though it is his off season when THE WEEK visits, his sponsor commitments have kept him busy, taking him all over the country.

Satish greets us with a namaste, hot tea, cashews, almonds and biscuits. We sit in the courtyard, the soft sun warming us up. We start from the beginning and talk about the evolution of the chubby child who became a world-beater.

Naturally, Tokyo 2020 is a talking point. The Olympic gold brought many changes for the Chopras, the village and Indian athletics. But, it was not an overnight flip. The house, for instance, was renovated four years ago when the son won the Asian Games gold.

The legend has only grown. With people now pouring in from outside Khandra every time Neeraj takes to the field, the family is building a large drawing room in the courtyard, away from the main house, to seat all the enthusiasts.

“I never thought this would happen, but once he started, he never looked back,” says the proud father. “We never did anything [of note] in our lives, but a child from the family did. We gave him attention and he went on to achieve great heights. Today, he has shown the way to all the children in the family, village and state.”

Inspired, the young ones of Khandra are now making a beeline for the Panipat stadium. The village does not have its own arena. “One of our girls has taken up javelin while three others are pursuing athletics,” says Satish. “They are all 10 to 12 years old.” Neeraj’s siblings―Sangeeta, married and based in Kurukshetra; and Savita, pursuing higher studies―are not into sports.

Uncle Bhim, who was in Delhi when we visited, speaks to THE WEEK on the phone and says that around 60 children in the village had taken up some sport. “The state government is planning to build a training ground in the village school,” he says. “Many parents seek our advice on how to proceed further, where to take their child for training. Five or six kids from our village are competing at the state level and a couple are at the national level.”

Bhim feels extra proud as Neeraj, having grown up in a joint family, had shown interest in sports because of his uncles. “We do not have a sporting background, we are farmers,” he says. “He was the eldest grandson in the family and was pampered a lot. He put on weight as a child. My younger brother Surinder took him to a local gym, but it shut down soon after. We then decided to take him to the Panipat stadium. The idea was to focus on his fitness and he soon started enjoying the workouts. It was there that he met Jaiveer, who introduced Neeraj to javelin.”

Satish credits Jaiveer for shaping the boy’s thinking. “He pushed Neeraj in the right direction,” he says. “He is both a coach and a brother to Neeraj.” Even now, though the Olympic champion works with elite foreign coaches, Jaiveer is still his sounding board.

As a young Neeraj started falling in love with the sport and his workload increased, the elders decided it was time for open school. He was a middling student, but then the Chopras never believed that other pursuits should take a backseat to academics. “There is no work that does not have an element of risk,” says Bhim. “Even in studies, where is the guarantee that every well-educated child would become an IAS or IPS officer? Just work hard and sincerely so. We encouraged him to take up sports, but we had limited means. He put all his effort into the sport. There was never any pressure of a medal from him. All we used to tell him was to play well.”

Says Satish: “Seven to eight hours of training in the day and he would study in the night for his exams at open school.” Neeraj is currently pursuing a bachelor’s degree from Lovely Professional University in Jalandhar, Punjab.

Neeraj was a naturally disciplined boy, but the Army training also helped. A subedar in the 4 Rajputana Rifles regiment, he joined the military in 2016, after he broke the world junior record. After his Olympic triumph, his promotion to subedar-major has been approved.

Neeraj is positive, pragmatic and has great clarity of thought―all traits that run through the family, starting from his grandfather Dharamsingh Chopra. Enjoying the afternoon sun, the patriarch sits with a group of friends and some youngsters in a broad lane outside a neighbour’s house. His hookah has the pride of place in the gathering. “I never thought he would go this far and make us all so proud,” says the emotional grandfather. “When he had graduated to the district level, he had told me that he would do even better. And now, life has totally changed, including the status of the family.”

Unlike relatives of athletes who get too stressed to watch, the senior Chopra is not faint of heart. “I watch all his events on television,” he says. “I do not take stress because winning and losing is a part of sport.”

More than the medals, what Dharamsingh is proud of is that his grandson’s behaviour has not changed. “He is a calm person,” he says, “who treats both old and young people alike, with warmth and respect.”

Neeraj’s javelin does soar, but his feet are firmly on the ground. “We do not want any of our kids, be it Neeraj or the rest, to forget their roots,” says Bhim. “Though he is home for a short time, he does all the chores. We do not want our children to be unaware of how to tend to the buffaloes or drive the tractor.”

But that is not to say that Neeraj is not pampered. Last year, after the Olympics, Saroj Devi had spoilt her son a bit too much. He had wolfed down her cooking, putting on 12kg. This time, though, he has kept himself in check. “His favourite food is choorma, matar paneer and aloo gobhi,” says the mother. “But sweets are off the table and he has been careful about stuff like parathas. He has been eating a lot of salads this time.”

An understanding woman, Saroj does not complain about the little time her son gets at home. “There is an air of happiness in the house when he comes back,” she says. “Our life has changed since he started winning at the senior level. So many people come home, but he has not changed one bit.”

There is an unwritten rule in the house. No one from the family will go for any of Neeraj’s big events. They watch him on the television. “We believe that if any of us goes for his competitions, he will get distracted,” says Saroj. “We do not want that.”

On his part, Neeraj has been keen on getting them involved. He recently took his parents, cousins and a few friends to Vijayanagara in Karnataka, where the JSW Sports headquarters is located―the company manages him on and off the field. He wanted his parents, especially, to experience the joy of flying.

The Chopras have had a clear policy from the beginning―there will be no interference in his training and other sporting matters. Not that they need to. Neeraj has been quite sorted from a young age about javelin and his dreams.

The biggest of which, the Olympic gold, seems to have spawned a mini javelin revolution in the country.

Seeing the spike in interest in the sport, the Athletics Federation of India celebrated August 7 this year as National Javelin Day. All state associations were asked to hold a day-long javelin event, and 32 units obliged. The response was heartening, the AFI later said.

There is also a visible change in India’s javelin camp, with Neeraj becoming the big brother to the upcoming throwers, encouraging them and passing on tips. Rohit Yadav, 21, was with Neeraj at the World Championships this July, but finished 10th with a throw of 78.72m. Neeraj had spent time with Rohit, assuring him that he would only gain from the experience of such an event.

D.P. Manu, who won gold at the 2022 National Games, has said that he admires Neeraj’s energy and confidence, and that the Olympic gold had brought more attention and assistance to them, too. Other throwers have also echoed this sentiment.

Neeraj’s impact, however, is not restricted to javelin, says Manisha Malhotra, head of sports excellence and scouting at JSW Sports. “I see a spring in the step of players and also coaches,” she says. “There is no doubt there are a lot more people interested in javelin now, but one must understand that Neeraj is THE gold medallist for this generation. Abhinav’s (Bindra) was way back in 2008. Neeraj is the first Indian athlete to win an Olympics gold, which has inspired the likes of long jumpers Murali Sreeshankar, Jeswin Aldrin and triple jumper Eldhose Paul to believe they can compete and win at the highest level. This was not the case earlier.”

The attention should only, and always, be on the sport, Neeraj believes. When there was some “reports” that Pakistani thrower Arshad Nadeem had “taken” Neeraj’s javelin during the Olympic final, he called out the speculators in an Instagram post, saying, “There was nothing wrong with him using my javelin to prepare... please do not use my name to push a dirty agenda.”

Neeraj and Arshad have been friendly―they shared a warm handshake on the 2018 Asian Games podium, and the Pakistani has called Neeraj his “brother”. When Arshad won gold at this year’s Commonwealth Games with a 90m-plus throw, Neeraj had congratulated him. He knows how sport can unite.

He also knows what his wins mean for the country, which is usually starved of athletics medals on a global stage. And so, after winning gold at Tokyo, he donated his javelin to the Olympic Museum in Lausanne, Switzerland. He said he hoped that its presence would serve as an inspiration for the younger generation.

He had also donated Rs3 lakh to the Central and Haryana state funds to fight the pandemic, and there are apparently plans to start a foundation in his name to explore how he can help future athletes.

While it is good that Neeraj has become an inspiring figure, says Malhotra, the AFI needs to do a lot more to capitalise on the gold. “I feel it is important to have major events like the Diamond League and the Asian Athletics Championships at home so that fans can get to see the action from close quarters,” she says.

JSW Sports has played a vital role in Neeraj’s growth, be it his training, competition, rehab or recovery. Malhotra describes him as “a good, sorted athlete”, and adds, “He has not reached his peak yet, in terms of performance. His technique needs some correction, yet he has delivered results at the right moment. He is comfortable in his own skin. He may not be the biggest or the fastest, but he produces big throws in competitions that matter. He is not overawed by the moment. He has figured out a way to be efficient.”

What makes him stand apart from his fellow Indian athletes is his work ethic, she says. “If you tell him he needs to do 80 sprints, he will not stop at 78 or 79,” she adds. “He is quite diligent in his training.”

What really endears him to Malhotra, however, is his maturity and ability to understand what is being asked of him. “He is quite easy to work with,” she says. “He will listen to what you are saying. He is obsessed with his sport.” When not training, Neeraj spends a lot of time watching javelin videos and analysing his competitors. As for pastime, he “loves photography and driving fast cars,” she says.

Not only a coach’s delight, Neeraj is also really in sync with his body and mind. Malhotra speaks of how, after throwing below par at an event in Lisbon, he was clear that he needed six weeks of training ahead of Tokyo. He did so, and it paid off.

“There is a lot of room for improvement in Neeraj’s throws,” says Malhotra. “The overall technique, strength and speed―there are several things that need to come together. We are trying to bring it all together.”

One positive trend that has made his coaching team happy is that he is now consistently throwing 88m-89m. “He was throwing 86m-87m in 2021,” says Malhotra.

Those harping on the 90m mark seem to be missing the forest for the trees. After all, you just have to throw farther than your rivals on that day, which Neeraj―a man for the big occasion―knows how to do.

His goal next year would be to defend his Asian Games gold and to better the World Championships silver in Budapest. He is currently at Loughborough University in the UK, training with coach Klaus Bartonietz and physiotherapist Ishaan Marwaha. Refreshed after a break, he is back to his happy place―on the field. And, on the horizon, is Paris 2024.