Mangaon. This tiny village in Kolhapur district does not exist on the maps of Maharashtra. Ask Google Maps where Mangaon is, and it will take you to Mangaon of Raigad district. Only when you type “Mangaon (Kolhapur)” would Google show you the Mangaon where B.R. Ambedkar entered public life by organising a conference of untouchables in March 1920.

Shyamrao Kamble, 80, of Mangaon has inherited memories of the conference. “My father was six years old then. My grandfather told him stories of it as he was growing up. My father told us the stories as we were growing up,” he said.

A thousand dalits from nearby villages attended the two-day conference, which drew a total of 20,000 people. Shahu Maharaj, king of Kolhapur and famed social reformer, attended it on the second day and said dalits had found a true leader. “Ambedkar will not only lead you, but also become one of the brightest leaders in India,” he said.

According to Jaysinghrao Pawar, an authority on Maratha and Kolhapur history, it was Baroda king Sayajirao Gaekwad who had told Shahu Maharaj about Ambedkar. “It was then that Shahu Maharaj decided to send Dattoba Powar (a cobbler who became the first dalit chairman of Kolhapur municipality) to invite Ambedkar to Kolhapur to discuss the problems faced by dalits,” said Pawar.

At Kolhapur, Ambedkar was taken to the palace in a horse-drawn buggy to meet the king. During their meeting, Shahu Maharaj and Ambedkar felt that a meeting of dalits should be organised. The king said Ambedkar should address the gathering.

“Shahu Maharaj never liked to be in the limelight,” said Pawar. “He rightly gave the credit of the Mangaon conference to Ambedkar. Had it been anyone else in Shahu Maharaj’s place, he would have become president of the conference to claim credit. But Shahu Maharaj made Ambedkar the president.”

Mangaon was chosen as the venue because the village had several leaders who followed the egalitarian ideology of the Satya Shodhak Samaj (Society of Truth-seekers, founded by Jyotirao Phule). One of them, Appasaheb Dadgonda Patil, was a Jain. “The Jains boycotted him because he dined with Ambedkar,” said Prof Pradnyawant Goutam, who has written two books on the conference.

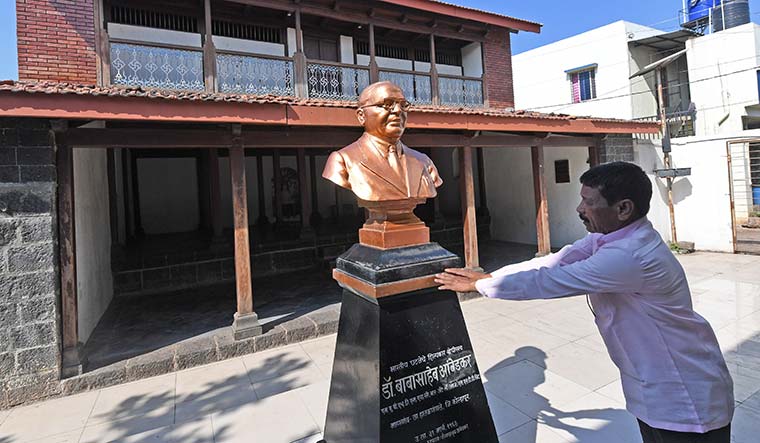

A century after the conference, the people of Mangaon have kept its memories alive. “All Buddhists of Mangaon contributed to construct a memorial to the conference,” said Murlidhar Kamble, president of the Buddhist community in the village. “We collected Rs3.02 lakh and constructed a pillar. We have inscribed on it 15 resolutions passed at the conference. A statue of Dr Ambedkar has been erected at the very spot where he stood to give his speech. We are also going to preserve the room in the boys’ primary school where he stayed during the conference.”

The places associated with Ambedkar are of huge significance to dalits. His family hailed from Ambadave in Ratnagiri district’s Mandangad taluk. Most houses in this village belong to Kunbis (a Maratha caste) and dalits of Ambedkar’s caste (Mahar). Many dalits here have Sakpal as their surname; Sakpal was Ambedkar’s original surname. So most of the modern-day Sakpals in Ambadave have added Ambedkar to their name.

Ambadave also has an Ambedkar memorial. “It stands at the same place where Ambedkar’s old house stood,” said Sudam Sakpal Ambedkar, 82. “Ambedkar came to Ambadave during school vacations when he was in class 5 to 9.”

Sudam lives in a house right in front of the memorial. He often plays the role of a guide, telling visitors a brief history of the Ambedkar family. “After Ramji Sakpal (Ambedkar’s father) retired from the army, he came to Dapoli (55km from Ambadave), where retired soldiers from his regiment had settled. The place was known as Camp Dapoli. He lived there for around five years and then moved to Satara, where he found a job. Satara also had far better educational facilities for his children,” said Sudam.

He said dalits in Ambadave take care of the memorial without any help from the government. “Daily cleaning, offering of flowers, and burning of incense sticks at the memorial are all done with the help of contributions from villagers. One family is in charge of all the work for one month; another family takes over the following month,” he said.

People from all over India visit Ambadave. Dalit families from Raigad and Ratnagiri districts throng the village on April 14 (Ambedkar’s birthday) and December 6 (his death anniversary) if they are not able to travel to Chaitya Bhoomi, the place in Mumbai where he was cremated.

“I wanted to visit Ambedkar’s native place since I was 15 years old. God only knows what would have been our people’s condition had it not been for his herculean efforts,” said Mohan Ahire, a retired Army man from Dharashiv district who came visiting with his family.

Ahire said they would visit Chavdar Tale in Mahad, around 50km from Ambadave. Ambedkar had sat on satyagraha in Mahad so that dalits, too, could drink water from the Chavdar tank.

Also read

- Why everyone wants a piece of Ambedkar

- How Ambedkar's family supported him in his journey

- Ambedkar trivia: “I will not die a Hindu”, weak in maths and more

- A 95-year-old's memory of Ambedkar's final speech as drafting committee chairman

- Ambedkar believed political democracy relied upon social cohesion, fraternity

- Ambedkar: Not just a dalit leader, but a thought leader

The Bombay legislature had passed an act in August 1923 giving dalits the right to access all facilities and institutions built by the British government. The Mahad municipal council subsequently passed a similar resolution. But neither the act nor the resolution could be implemented because of opposition from Hindu conservatives.

The resolution was championed by upper-class progressives like Surendranath Tipnis, Gangadhar Sahasrabuddhe and Anant Chitre. The trio supported Ambedkar when he announced the satyagraha. Tipnis, who was municipal council president, and Sahasrabuddhe opened all public facilities for dalits, and invited Ambedkar to address a public meeting. It was decided that, after the meeting, all people would go to the Chavdar tank and drink from it. Thus, more than a thousand dalits drank from the tank on March 20, 1927.

Vinayak Hate, a former supervisor in the education department, said his uncle Sitaram Hate had participated in the satyagraha. “Dalits were attacked while they were leaving a day after the satyagraha. Ambedkar told them not to react,” said Hate. “The Mahad satyagraha lifted our spirit. Because of Ambedkar, our people started studying. Many were inspired to join the army like his father.”

Ambedkar burnt the Manusmriti in Mahad in December 1927. “This time, too, progressive upper-caste leaders like Sahasrabuddhe supported Ambedkar,” said Hate. “After independence, we erected the Krantistambh (a pillar of revolution) on that spot. Ambedkar’s son took the initiative for this. Ambedkar’s ashes were placed at the base of the Krantistambh.” A local Muslim family, he said, donated the land for the memorial.

Hate recalled how, as a four-year-old, he had walked 12km from Veer to Mahad in 1957 to see the Bhim Jyot, a flaming torch that was taken across Maharashtra after Ambedkar’s demise. “My father, Sahadev Hate, insisted that we pay our respects to the Bhim Jyot when it reached Mahad,” he said.

On March 3, 1930, Ambedkar began an agitation for the entry of dalits to the Kala Ram temple in Nashik―so named because both the temple and its idol (Lord Ram) are made of black stone. A day before the agitation, 15,000 people participated in a rally led by Ambedkar and his close associate Dadasaheb Gaikwad.

The agitation went on for five years. In 1935, Ambedkar said at Yeola in Nashik district that he had decided to renounce Hinduism. “The Kala Ram temple agitation is a challenge to the upper-caste Hindu mind,” wrote Ambedkar in Majhi Atmakatha (My Autobiography). “For centuries, upper-caste Hindus have denied us basic human rights. Our satyagraha is a way of asking them a question whether they are willing to consider us as human beings. They have treated us worse than their cats and dogs. Now, through this satyagraha, we are asking them whether they are willing to give us human rights.”

As upper-caste Hindus refused to budge, Ambedkar called off the satyagraha in 1935. At a meeting of dalits at Yeola on October 13, 1935, he declared that he was renouncing Hinduism.

“‘I was born a Hindu, but I will not die as a Hindu’ were his words,” said Chandrakant Wagh, a dalit activist from Mukhed, a village close to Yeola. “He felt that the status of dalits would not improve if they remained Hindus. And that is why he made the historic announcement.”

Ambedkar was at Mukhed on October 12, a day before he went to Yeola. “He stayed at our home,” said Wagh. “My grandfather Kisan Bhikaji Wagh was an activist in his movement. Ambedkar had come to our village after a riot. Dalits had taken out a religious procession; to counter it, upper-caste Hindus also took out a procession. A dispute arose over whose procession would pass through the village first. Upper-caste Hindus attacked the dalit procession and beat up several participants.”

Ambedkar stayed at Mukhed for a night. The following day, he went to the Vitthal Rukmini temple there to seek blessings. He entered the temple, had ‘darshan’ and announced that the temple was now open to all dalits. That is how the temple in our village became open to dalits,” said Wagh. “And, from Mukhed, he walked 7-8km to Yeola.”

The place where Ambedkar made the announcement to leave Hinduism is now called Mukti Bhoomi. A stone pillar describing the course of events on October 13, 1935, has been erected where he addressed the dalits during the rally. A big memorial has also been constructed.

“There are also plans to build a museum, a Pali and Sanskrit research centre, an amphitheatre, and a school and a hotel for Buddhist bhikkhus (monks) who come here to study,” said Pallavi Pagare, research officer and manager at the Mukti Bhoomi memorial at Yeola.

Every year, lakhs of people come to Yeola on October 12 and 13 to pay tribute to Ambedkar at Mukti Bhoomi. “Last year, the number touched almost six lakh,” said Pagare. “They come not just from India, but from across the world.”