Stacks of colourful kites and reels of twine crowd out the small one-room commercial establishment located in the quiet middle-class locality of Dattapada Road in Borivali, Mumbai. Except for the board outside, there is nothing to show that this is the registered office of the Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Party (SVPP).

Sitting on a plastic stool in the centre of the tiny room, the elderly Dashrath Bhai Parekh, who is the national president of the party, is busy making bundles of kites. He says he is in the business of supplying kites, while politics for him is a means of doing social work. He claims he has worked with the likes of Morarji Desai and Sharad Pawar and Mayawati before forming his own party in 2006. Parekh’s party, however, has recently caught the attention of the Election Commission and the income tax authorities for alleged financial irregularities worth crores of rupees. Parekh refutes the allegations and says that his party’s donors include charitable organisations, businesses, the textile industry, diamond merchants and those in the field of real estate, and all funding is aboveboard. He says he has provided the authorities with all relevant documents since the party’s premises were raided by income tax sleuths in September 2022.

In Mumbai again, on Swadeshi Mills Road in Chunabhatti, the only remnant of the Jantawadi Congress Party at the address listed as its national office is a rolled up tricolour lying on the balcony of a modest two-storey building. Anant Sawant, a senior citizen who owns the building, had rented it out to the party. Sawant says he asked party president Santosh M. Katke to vacate the premises after he came to know that the party indulged in wrongful activities.

A few kilometres away, deep inside the slums of the Mhada Colony in Wadala, a shanty doubles as the communication address of the Jantawadi Congress Party in the Election Commission records. Katke lives here with his wife and two kids. That Katke could be at the centre of an alleged scam worth crores of rupees shocked his neighbours, since the quiet man would pick up his bag and go to work every morning and come back in the evening like any normal person next door. However, when income tax officers raided the hutment and the party office last year, out came allegations that the party was involved in money-laundering worth at least 06 crore. The hole-in-the-wall party had suddenly started receiving huge contributions. And, according to the Election Commission, it could have links with the SVPP.

Far away from the metropolis, in the hinterlands of Uttar Pradesh, a similar story unfolds. In a bustling market in Sultanpur, a two-and-a-half-hour drive from Lucknow, a watch repair shop is also the address of a little known entity called the Apna Desh Party. What lies behind the benign veneer of the small commercial establishment-cum-office of a political party is the story of a huge scam. Abdul Mabood, who owns the shop, is the president of the party. The outfit has been accused of misusing the income tax exemption for the donations that they receive. Mabood, however, claims he is himself a victim of a fraud committed on him by one Razak, whom he had appointed as the president of the party’s state unit in Gujarat. Razak, Mabood claims, misused the PAN card of the party without his knowledge to collect funds and even opened a bank account in Gujarat for the purpose. He says he has filed a police complaint against Razak and would be surrendering the PAN card, too. The Election Commission says the party represents a curious case of two presidents and it got more than Rs100 crore in donations despite showing little political activity.

In the dusty lanes of the industrial hub of Kanpur, the alleged financial misdeeds of the Jan Raajya Party―whose registered address is in Prayagraj and whose authorised signatory is mentioned in Election Commission records as Ravi Shankar Yadav―resulted in income tax raids in September 2022. The party is accused of flouting norms to get income tax exemption and the Election Commission is doubtful about its claims of having spent most of the donation on party workers since the party has indulged in little political activity.

Among the addresses raided in Kanpur was the residence of Omendra Bharat, who had co-founded the party with Yadav in 2010, and the address was then mentioned as the official address of the party. Bharat, however, later severed ties with Yadav to join the Aam Aadmi Party. According to Bharat, Arunesh Kumar Singh, who was then president of the party, had filed an FIR against Yadav over alleged financial wrongdoings at the Naubasta police station of Kanpur in November 2016. Yadav, on the other hand, refutes all allegations. He says his differences with Bharat and others with regard to the leadership of the party arose only after they left to join the AAP. He claimed that the FIR was filed because he had approached the Election Commission against Bharat and others nominating their family members to leadership positions in the Jan Raajya Party.

Welcome to the world of sham political parties, or organisations that election authorities call Registered Unrecognised Political Parties (RUPP). The address of communication indicated as a shop or a slum dwelling, as the Election Commission found out during its verification drive of these parties, per se is not an issue. But the massive financial scam that such organisations are involved in raises concerns about financial wrongdoing that range from income tax evasion to money-laundering. The amounts involved could run into thousands of crores of rupees.

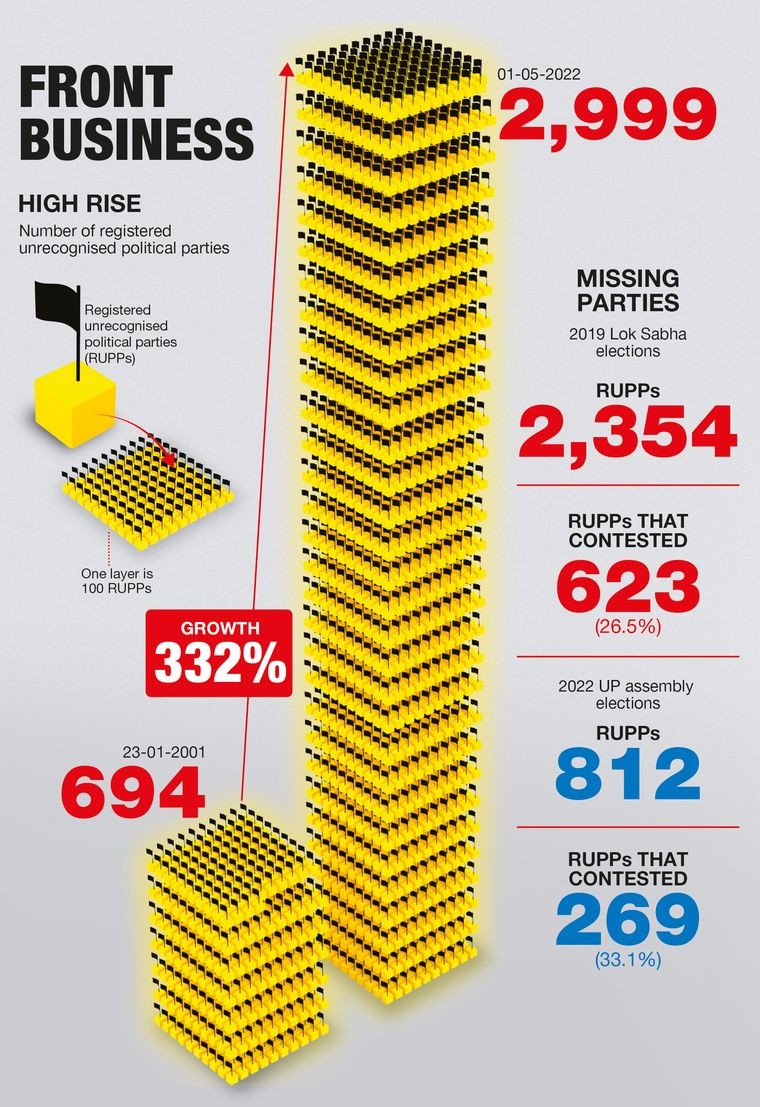

This and much more came to light when the Election Commission initiated in mid-2022 a clean-up drive against such parties. To begin with, the sheer explosion in their numbers is mind-boggling. There were around 2,300 parties in March 2019 and the number has now crossed 3,000, an increase of around 700 in just two years. Since 2001, there has been a 300 per cent increase in the number of such parties.

RUPPs are parties that are either newly registered or those who have not secured enough percentage of votes in assembly or Lok Sabha elections to become a state party or those who have never contested elections since they were registered. As against around 3,000 RUPPs, according to a notification issued by the Election Commission on September 23, 2021, there were eight national parties and over 60 state parties. Of the state parties, the AAP has since become eligible for national party status.

The Election Commission’s clean-up drive was guided by the assessment that a majority of the RUPPs had little electoral activity to show. Only 673 parties contested in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, which was less than 30 per cent of the total RUPPs. Last year, only 265 RUPPs out of more than 800 registered parties in Uttar Pradesh contested the assembly elections.

The Election Commission’s action initiated in May 2022 has hit upon what could be just the tip of the iceberg of large-scale use of such entities to indulge in financial impropriety. The RUPPs are entitled to receive contributions from the public and organisations and enjoy tax exemption under the Income Tax Act. The donation received by the party is completely exempt from income tax and the donor is also entitled to claim IT exemption for the amount donated. However, Section 29C of the Representation of People Act mandates certain public disclosures about the donations received by them and their expenditure.

Over 92 per cent of the RUPPs had not filed their contribution report for the year 2019-20. As many as 199 of them claimed IT exemptions totalling Rs445 crore in 2018-19. In 2019-20, 219 RUPPs claimed IT exemptions worth Rs608 crore. Of these, 66 had not submitted their contribution report. For the year 2019, as many as 2,056 RUPPs have not yet filed their annual audited accounts. Of the 115 RUPPs in Assam, Kerala, West Bengal, Tamil Nadu and Puducherry, which went to polls in early 2021, only 15 have filed their election expenditure statement.

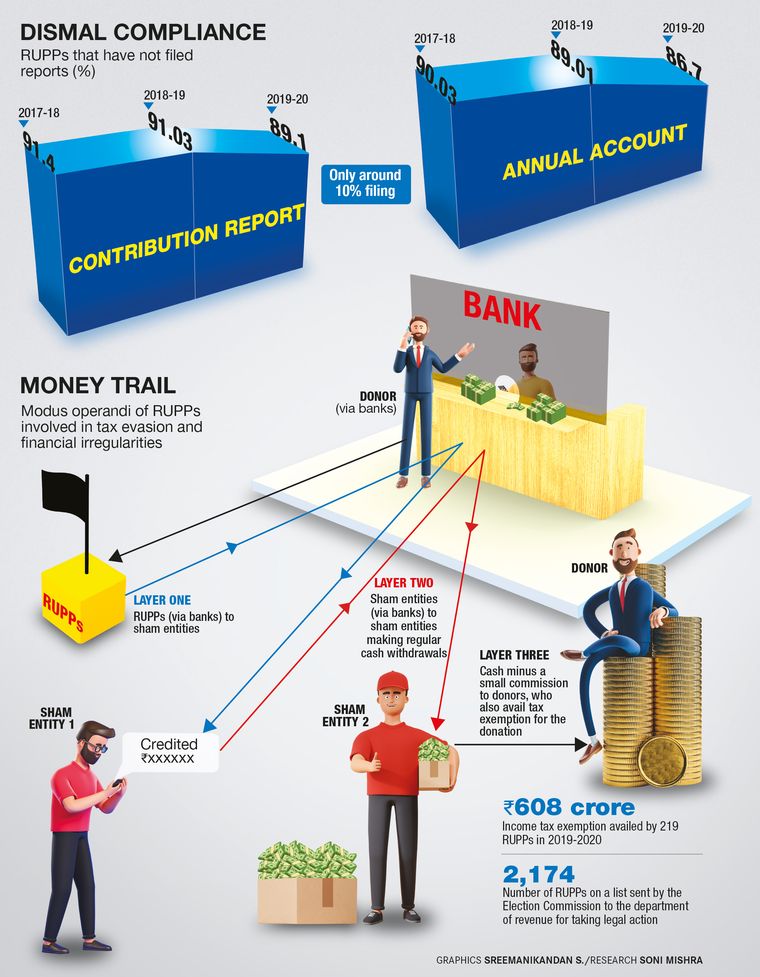

The Election Commission’s drive to cleanse the RUPP ecosystem revealed that many of these parties are involved in taking bogus donations by cheque or banking channels and returning the money in cash after deducting their commission and routing the money through different layers (see infographics). To begin with, this is a loss of revenue to the exchequer since these parties and their donors can both claim relief from income tax. Also, besides the loss of revenue, there is also the risk of diversion of money.

Chief Election Commissioner Rajiv Kumar described the clean-up of the RUPP space as a daunting challenge. He said: “The challenge is enormous to not only clean up the political space of sham entities, but also to hammer the message of financial accountability, propriety and transparency along with due and lawful participation in the electoral process as per the mandate of the Constitution.”

He said the issue before the Election Commission was the crowding of political space by RUPPs who do not contest elections and misuse the facility given to them under various laws. “A course correction to enforce compliances, strengthen the democratic process and increase transparency in financial affairs is much required,” he said.

A list of 2,174 RUPPs which have not submitted their contribution reports was provided by the Election Commission to the department of revenue. The Income Tax Department conducted raids on 23 RUPPs in 110 locations in September 2022.

What has come to light is that many of these organisations are involved in either evasion of income tax of massive proportions, or even money-laundering, with one party being probed for alleged whitewashing of black money post the demonetisation of November 2016. There are indications that some of them even acted as conduits for collecting donations that may be meant for purposes other than electoral activity.

Chief Electoral Officer of Maharashtra, Shrikant Deshpande, described the May 2022 order of the Election Commission on RUPPs as a watershed moment in the clean-up drive against such parties. “The action sent a strong message that the Election Commission is determined to clean up the system. It stressed upon the need for transparency and financial accountability,” he said.

What came as a shocker to the Election Commission was the brazenness with which many of these parties were involved in financial irregularity, the modus operandi based on taking donations through digital means or through cheques, layering further transactions through banking channels before it made its way into cash transactions.

The clean-up drive began with verification of the details provided by the parties, such as their address and details of office-bearers, and also taking into account their electoral activity or lack of it. In May 2022, the Election Commission had deleted from its list of registered parties 87 non-existent RUPPs whose addresses were found to be false upon either physical verification carried out by the concerned chief electoral officers or based on report of undelivered letters or notices from the postal authority.

In June 2022, 111 more such parties were deleted from the list since they had failed to meet with the statutory requirement of informing the Election Commission about their genuine address of communication. In September 2022, the poll body delisted 86 more non-existent RUPPs. Also, as many as 253 RUPPs were declared as inactive and delisted since they have not contested a single election either to the assembly or to the Lok Sabha in 2014 and 2019. They had also failed to respond to the letters or notices delivered to them by the Election Commission. In all, since May 2022, the Election Commission has delisted 537 RUPPs which were found to have defaulted on complying with various statutory requirements.

The action taken against the RUPPs for not complying with statutory requirements has been described by Election Commission officials as a roundabout way of closing in on their financial wrongdoing and putting a stop to it. While announcing action against the RUPPs, they are given 30 days to file any grievances. Very few of these RUPPs have appealed against the action taken against them. It is felt that since these parties have a lot to hide, they are unlikely to appeal against their delisting.

Another matter of concern is the possibility of these parties fronting as proxies or surrogates for other parties, participating in informal political groupings to receive irregular funds, and blocking campaign spaces, names and symbols. Major General Anil Verma (retd), head of the Association for Democratic Reforms, said weeding out parties which were not participating in elections or not submitting financial reports was essential. “It should be a continuous process,” he said.

The Election Commission does not have the power to de-register parties. So it came up with an alternative way, called delisting. Experts, however, feel that delisting is not enough to deal with errant parties since it does not stop them from continuing to claim income tax exemption. “The Election Commission has delisted a certain number of parties. However, this basically only means that they cannot get a symbol and hence cannot contest elections, which many of them anyway do not. They continue to exist as parties and can continue to get funds and avail of income tax exemption. For the exemption to be withdrawn, an amendment would be required in the Income Tax Act,” said P.K. Dash, former head of the Election Commission’s expenditure control division.

Former chief election commissioner T.S. Krishnamurthy said legal lacunae needed to be fixed for better regulation of political parties. “There are restrictions and regulations with regard to political parties, but there are no codified rules to monitor their working,” he said. “A distinct law that deals with regulating political parties is absolutely required. Right now, they are let loose and not easily regulated.” He also said a stringent system of registration was needed and that a party that did not contest an election for ten consecutive years should automatically get de-recognised.

Krishnamurthy also reiterated the idea of a National Election Fund that would function under the aegis of the Election Commission and donations to which would be exempt from tax. He said it would be from this fund that parties would get their funding and not directly from donors.

A lot more remains to be discovered about the murky world of the small political party.

A case of two presidents

Apna Desh Party, Uttar Pradesh

IN THE middle of a bustling market in Sultanpur, Uttar Pradesh, a watch repair shop doubles as the registered office of the Apna Desh Party.

Abdul Mabood, who is listed in the records of the Election Commission as the national president of the party, owns the watch repair business. In two different communications to the Election Commission, Mabood mentioned that for the financial years 2016-17, 2017-18 and 2018-19, the party did not receive any membership or financial contributions. According to him, the income and expenditure of the party were both zero in these years.

However, one A. Razak, claiming to be party president, was signing letters and forwarding financial documents to the Election Commission, which showed that donations were received. Also, the annual audited accounts of the party were signed by one Abdul B. Razak Pathan in the capacity of treasurer of the party. Furthermore, for the year 2018-19, Mabood was mentioned in the verification part of Form 24A of the Conduct of Election Rules, 1961, as president. But the declaration was signed by A. Razak as president.

The auditor of the party mentions the Sultanpur address as the registered address of the party, and contrary to Mabood’s claims, states that the party received a contribution of Rs37.13 crore in 2017-18, and Rs80.06 crore in 2018-19. Of the Rs37.16 crore, Rs27.47 crore and Rs9.46 crore were shown as expenditure towards publicity expenses and public welfare expenses, respectively. A tax exemption of more than Rs100 crore was given to the party by the Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT).

The party office was raided by the income tax department in September 2022.

Note ban and whitewash

Jan Raajya Party, Uttar Pradesh

THE JAN Raajya Party, whose office is in Dhumanganj, Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh, received Rs11.65 crore as contribution from 2018-19 to 2020-21. Despite the party not filing its contribution report to the Election Commission, it received income tax exemption.

The income tax department raided the premises of the party and the residence of its president Ravi Shankar Yadav in September 2022. Although the party has not had much political activity to show, most of the contribution was shown as having been spent towards “party workers’ expenditure”. The audit reports filed by the party, too, were not detailed.

Election Commission officials, in the course of verifying the credentials of the party, came upon an old complaint filed by an erstwhile president of the party against Yadav―who was earlier the treasurer of the party―and others for allegedly whitewashing black money through the party’s account post demonetisation. The complaint was filed at Naubasta Police Station, Kanpur.

Gold and much more

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Party, Maharashtra

IN THE middle class locality of Dattapada Road, Borivali East, Mumbai, a small commercial establishment is listed as the address of the Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Party. It has some political presence to show in terms of holding events or taking part in elections, and its president Dashrath Bhai Parekh has held media interactions. However, it has caught the attention of the Election Commission for alleged lapses in its financial dealings.

According to the audited balance sheet and audit reports submitted by the party, it received donations worth Rs29.87 crore in 2018-19 and Rs41.19 crore in 2019-20. However, there was a mismatch in the balance sheets of consecutive years, and it is suspected that more than Rs1 crore was siphoned off. In addition to the usual non-compliance of even basic auditing norms, myriad expenses were shown, including investment in gold worth Rs1.78 crore.

Donate and win exemption

Bharatiya Rajnitik Vikalp Party, Bihar

THIS IS the curious case of a party that is registered in Bihar, but is running its operations from Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh. Its registered address is in Bakhtiyarpur district in Bihar. However, according to the Election Commission, the party has two possible alternative addresses: one in Khanjawala Road, Delhi, and the other in Indirapuram, Ghaziabad.

While the party is registered in Bihar, most of the contributions came from Delhi/National Capital Region. The only report of the party available on the website of the chief electoral officer of Bihar is the contribution report for 2018-19. As per information available with the Association for Democratic Reforms, the party collected Rs25.44 crore in 2019-20.

The annual audit, balance sheet or income/expenditure account of the party could not be found on the website of the chief electoral officer. A notice for compliance was issued to the party on May 28, 2022. Interestingly, the party actively advertises the income tax exemption benefits of donating to the party.

Donation out of a donation

Kongunadu Makkal Desia Katchi, Tamil Nadu

THE PARTY, with its office in Namakkal, Tamil Nadu, had in 2018-19 shown donations worth Rs22.64 lakh. In the following year, its income soared to Rs15.77 crore. This was mainly because of a donation of Rs15 crore which the party received from the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam. The party had contested the Lok Sabha elections in 2019 in alliance with the DMK. It is not clear how the huge contribution from the DMK was utilised by the smaller party as neither its audit report nor its election expenditure statement for the Lok Sabha polls in 2019 could be seen on the website of the chief electoral officer, Tamil Nadu.

Though there is no bar on such a transaction, the question that has to be answered is whether the donors of the DMK were aware that a substantial chunk of their donation would be further donated to an unrecognised party.

A windfall and charity

Bhartiya National Janta Dal, Gujarat

THE DONATION received by the party in 2016-17 and 2017-18 was Rs1.47 lakh and Rs1.62 lakh, respectively. It showed a sudden jump to Rs4.32 crore in 2018-19. Of that, Rs4.23 crore was shown as spent on ‘other charitable objects’, without furnishing any details.

The contribution report for 2018-19 was filed in March 2021, almost one and a half years after the due date. It was incomplete and neither the address nor the PAN of the donors, and in many cases, not even their names, were provided. Therefore, the party would not be eligible for exemption under the Income Tax Act.

The audit report for 2018-19 mentions the donation of Rs4.32 crore as ‘donations in cash’, perhaps a typing error as the contribution report for the same year gives a list of 289 donors, all by electronic transfers.

Two parties, one auditor

Jantawadi Congress Party, Maharashtra

THE COMMUNICATION address of the Jantawadi Congress Party leads to a small dwelling in a slum in Mhada Colony, Vadala, Mumbai. The tax audit reports filed by the party for 2018-19 and 2019-20 were submitted by a letter dated December 25, 2021, signed by party president Santosh M. Katke.

As per the accounts provided by the party to the Election Commission, its income from donations in 2018-19 was just Rs2,000, which showed an astonishing jump to Rs5.83 crore in 2019-20.

Interestingly, the auditor of the party, Kashyap Kumar Ishwarbhai Patel, is also auditor of the SVPP. Moreover, Patel was appointed auditor of both parties on the same date―January 5, 2021, and the letters appointing him as auditor, by both the parties, bore the same reference number. The Election Commission suspects that the two parties are run by the same set of people.

The party did not submit its contribution report for 2018-19 and 2019-20. It is not clear whether the party has claimed exemption. Income tax searches were conducted on the party’s premises.

Newbie flush with funds

Shashakt Bharat Party, Rajasthan

THE PARTY was registered with the Election Commission on November 15, 2019, with its address in Chittorgarh, Rajasthan. Within a year of its inception, which coincided with the Covid-19 pandemic, the party collected more than Rs2.67 crore from 159 donors spread all over the country. It spent more than Rs1.42 crore on ‘election/general propaganda’ and more than Rs97 lakh on ‘administrative costs’ in its first year―although there were no elections in Rajasthan during this period. In 2020-21, the party collected more than Rs6.9 crore, of which Rs4.31 crore was spent on ‘election/general propaganda’.

Another fact that drew the attention of the Election Commission was the change of authorised signatories. While one Anurag Tamboli was the authorised signatory for 2019-20, two others, Mukesh Mali and Lakhan Khatik, took that position for 2020-21.

Cash or cheque?

Garvi Gujarat Party, Gujarat

THIS PARTY claimed to have received more than Rs4.6 crore in 2019-20, and to have spent most of it during that year. The auditor simply mentioned in the audit report that the physical implementation of the programmes or activities of the party were not seen by them. The auditor further stated: “...the practice of cash payments should be gradually declared”. Reading both these statements together, along with the skeletal balance sheet and receipt-payment account and lack of cash flow statement, the financial affairs of the party are suspect. The party’s office was raided by the income tax department in 2022.

Shrouded in mystery

Jan Sangharsh Virat Party, Madhya Pradesh

A SENIOR Election Commission official described the Jan Sangharsh Party’s case as the most cryptic representation of financial affairs of a political party. The address mentioned in the audit report of the party is in Ahmedabad, while its registered office on the Election Commission website is in Sant Ravidas Ward, Sagar district, Madhya Pradesh. Further, the audit report is countersigned by three persons as president, secretary and treasurer. But their names have not been mentioned.

The audited profit and loss account merely mentions an indirect income of Rs1.42 crore and indirect expenses of Rs1.38 crore in 2019-20; no details have been provided. The Election Commission’s inference is that the auditor did not know from where the money has come and where it has gone. The name of the party is in the defaulter list for non-filing of contribution report and is therefore not eligible for claiming exemption under the Income Tax Act.