Gurjant Singh sat with his hands folded, shifting uncomfortably on his seat as he glanced first at the burly policemen and then at his mother, anxious to catch her expression. Charanjit, her face half-hidden by her dupatta, had been staring him down. As she spoke to the 17-year-old, her voice got louder and shriller. Gurjant, six-foot tall, trembled.

Then, turning to the cops who were blaming mothers for not noticing their sons’ errant ways, she screamed: “I can tell you I was strict with him. He fell into bad company without understanding the dangers involved.”

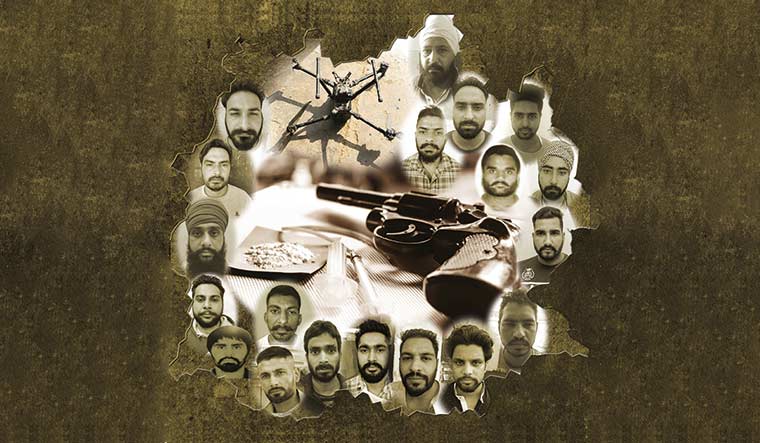

It all started when Gurjant became friends with Gurpreet Singh alias Gopi Numberdar, 18, of Naushehra Pannuan village in Punjab’s Tarn Taran district. The duo would hang out together on bikes. One such ride on a dusty afternoon took an ugly turn when a drone from Pakistan dropped an RPG (rocket-propelled grenade), the kind that mujahideen in Afghanistan used. Their friends picked it up, though they did not know what was inside the package. Gopi knew. He, said the police, was using teenagers to execute a plan to fire the RPG at the Sarhali police station in Tarn Taran on December 9, 2022. He said he did this for Canada-based gangster-turned-terrorist Lakhbir Singh Sandhu, better known as Landa.

Gopi is now in jail, but Landa is wanted. The National Investigation Agency has offered a reward for information on his whereabouts. He is also wanted in the RPG attack on the police intelligence headquarters in Mohali on May 9, 2022.

The NIA is investigating the larger conspiracy behind five such acts of terror in Punjab in the past 13 months. These include targeted killings and gunrunning operations that, said officials, have been traced back to Harwinder Singh Rinda, who lives in Lahore and is backed by Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence. Rinda, who is from Gopi’s village, is a dreaded name in the border districts and is wanted by the police in several states.

Investigators said that Rinda supplied RPGs and AK-47s from across the border. Landa used his network of boys to conduct a recce, and arrange hideouts and logistical support to carry out the Sarhali attack. Besides Landa, Gopi’s handlers Satbir Singh alias Satta and Gurdev alias Jassal have fled the country.

State of shock: Parents of the accused in last year’s RPG attacks at the district police office in Tarn Taran | Sanjay Ahlawat

State of shock: Parents of the accused in last year’s RPG attacks at the district police office in Tarn Taran | Sanjay Ahlawat

Landa and Satta, both in their 20s, belong to the same social milieu as Gopi, playing kabaddi, and hunting and selling dogs. “We used to play together in summer afternoons, learning tricks from each other. Gopi was my friend while Landa was our senior,” said Gurjant, horrified that his friendships have gone awry yet unmindful of the ramifications of his actions.

Another teen, Gurdeep, had given shelter to the Sarhali station attackers. He sneaked them onto his terrace the night after the operation. “I was not aware of their plans,” he said. “We are friends.” The boys ate good food, had a few drinks and returned to their homes.

Gopi and his boys are part of a new crop of juveniles embracing a culture of drugs, guns and gore (glorified in some Punjabi pop music) to make a quick buck and become Instagram-famous. What has set alarm bells ringing in the police circles is that these teens are being used as foot soldiers in nefarious operations.

Close shave: (From left) Inspector Prabhjit Gill with Nishan Singh and Ramanbir, who were unknowingly caught up with gangsters, but were let go with a warning | Sanjay Ahlawat

Close shave: (From left) Inspector Prabhjit Gill with Nishan Singh and Ramanbir, who were unknowingly caught up with gangsters, but were let go with a warning | Sanjay Ahlawat

Of late, a transnational gangster-terrorist network has rocked Punjab, with a threefold rise in crimes since 2019, said a state counter-terrorism official. This network is carrying out acts of terror, drugs trade and gunrunning not only in Punjab, but also in Jammu and Kashmir, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan. For instance, the Lawrence Bishnoi gang, which killed rapper Sidhu Moose Wala last May, has roots in Haryana, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh.

On February 21, in a major crackdown on gangsters working with terrorists and drug smugglers, the NIA raided 76 locations in eight states and seized arms, ammunition and 02.3 crore in cash.

“Gangs lure small-time criminals in jails with weapons, money and promises of a life abroad,” said Amit Prasad, additional director general, Punjab Police.

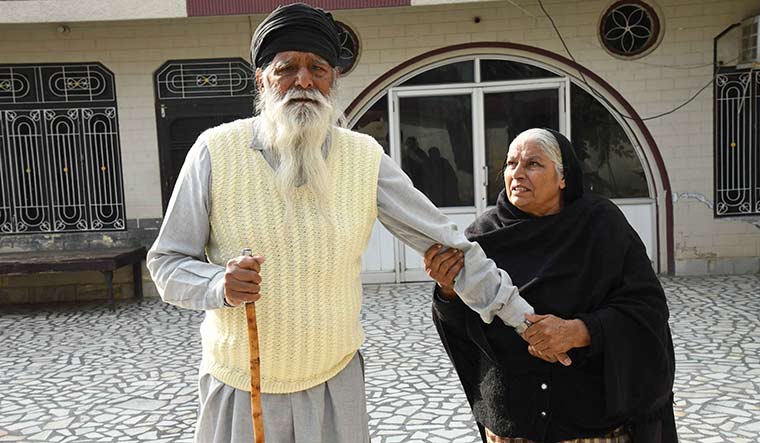

Home is where the hurt is: Parents of gangster-turned-terrorist Lakhbir Singh, alias Landa, at their home in Tarn Taran, Punjab | Sanjay Ahlawat

Home is where the hurt is: Parents of gangster-turned-terrorist Lakhbir Singh, alias Landa, at their home in Tarn Taran, Punjab | Sanjay Ahlawat

In the past five years, the state police have arrested 4,000 gangsters. In April, Chief Minister Bhagwant Mann set up an anti-gangster task force. It has since arrested 508 gangsters and confiscated arms and drugs from them.

On February 17, the Union home ministry declared Rinda a terrorist, and said that he was associated with the proscribed Babbar Khalsa International. It also declared two more organisations―Khalistan Tiger Force and Jammu and Kashmir Ghaznavi Force―as terrorist organisations.

But these steps are just a start; the damage at home is deep. Gopi’s parents, Gursharan and Simranjit Singh, are in shock. “Kids are being used in terror acts,” said Simranjit, who is a panchayat member. “They are being misused and trapped by foreign gangs who are giving them money and pistols. They knew each other as children, so why are they targeting our kids?”

The police have pardoned seven juveniles, including Gurjant, as they were first-time offenders; their families have been asked to watch them closely. They have also let go some adults who unknowingly helped the gangs. For instance, Nishan Singh alias Happy, Gopi’s cousin, was tricked into carrying arms.

“It will not only give the juveniles a chance to join the mainstream, but also send a message to the gangsters that the police have a humane face and a good heart,” said Gurmeet Singh Chauhan, senior superintendent of police, Tarn Taran.

Gopi had apparently watched YouTube videos on how to fire the RPG and had hidden it in a tube well. He gave friends like Gurjant money to buy hoodies and phones so they could check out the target building.

“I am wearing it today,” Gurjant told the policemen, who did not know whether to laugh or cry. “We can only guide them,” said Davinder Singh Ghuman, deputy superintendent of police (detective) in the Crime Investigation Agency. “These boys are given cash to buy clothes or mobiles. Sometimes they are given a packet of cocaine that can fetch them much more money.” Ghuman has issued yellow cards to nearly 50 boys who are to be monitored closely.

Satnam, 17, is one of them. The son of an ex-Army man, he is keen to join the forces. “Gopi was my friend,” said the frail boy, standing with a big schoolbag outside his coaching centre. “He asked me to keep a packet in my bag.” The packet, the police found, had a pistol and Rs2.5 lakh; Gopi had given it to him a day before the Sarhali attack. “The boy is innocent so we let him go,” said Ghuman.

The gangsters are not so generous. Jagjit Singh, who owns a petrol pump in Tarn Taran, said he was getting extortion calls from Landa and Satta. “I have spent so much money getting my car bulletproofed but they said they could still blow it up,” he said.

They are not even sparing their former friends. Gurdev Singh, who was once Satta’s friend, knew that he loved a girl from the village. But as Satta’s “job” was unsavoury, Gurdev helped the girl marry another man. “This upset Satta and he threatens me with consequences,” said the 40-year-old. Satta is learnt to have fled to Spain six months ago.

Even some policemen are living in fear. Paramdeep Singh, assistant superintendent of police in the Crime Investigation Agency, had interrogated Landa when he was jailed in 2015 for carrying 300gm of heroin. “I got an extortion call from Landa asking me to arrange around Rs50 lakh for him,” he said. “When I refused, he threatened to kill me.” Paramdeep is now high on Landa’s hit list and every intelligence report mentions it. “Last year, he called to say he would target me if I went to my village to meet my family. I have stopped visiting them.”

Paramdeep was the last policeman who spent time with Landa before he got out of jail in six months and fled the country on a fake passport. “He was never remorseful,” said Paramdeep.

Six years later, there is regret and remorse in Landa’s house. The parents―former serviceman Naranjan Singh, 76 and Parminder Kaur, 66―were surprised by our visit. “It has been ages since someone has come here,” said the frail, bent woman as she limped to her kitchen to fetch us water. “My boy tried to save himself from the allegations and was forced to flee,” she said, sobbing. “I am not saying he did something wrong or not, but look at us today. He cannot meet us and we cannot go and see him as our passport has been taken away. His father is so unwell. I try to take him to the doctor myself. I have to be strong to take care of him.”

There are bullet holes on her bedroom window. Rival gangs tried to kill them, she explained. There are CCTV cameras at the gate and inside the house. On the walls are pictures of Landa’s immediate family, but not his. “We have not seen or heard from him,” Parminder said. “We get to see his picture on television only. We have nothing left to look forward to.”

Investigators claimed that the son has built a comfortable life in Canada, far from his mother’s embrace.

Landa and his ilk, in fact, are a reason for tenuous diplomatic ties between India and Canada over the issue of extremism growing on foreign soil. There appears to be no extremism in Punjab, not even a whisper of the Khalistan movement. But forces inimical to India find it easy to tap the Punjabi diaspora on foreign shores to fan unrest. Though only a tiny section of this community is pro-Khalistan, they have carried out protests in Canada and the US, and recently attacked people of Indian origin in Australia for protesting the Khalistan Referendum. Notably, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Liberal Party relies heavily on the Sikh-Canadian vote bank.

“We have conveyed our firm rejection of the so-called Khalistan Referendum and politically motivated exercises by extremist elements,” said India’s external affairs ministry spokesperson Arindam Bagchi.

The challenge is not just for Punjab. The ISI-backed Khalistani nexus poses a threat to the host countries as well, especially when gang wars spill over into their streets. The murder of Ripudaman Singh Malik, who was acquitted in the 1985 Air India bombing case, highlights the threat from extremism. Malik, a Canadian citizen, was shot dead in July 2021 in British Columbia. Security experts felt that he was keen on exposing the nexus between the ISI and Khalistani groups.

“The Canadian government, for many years, had a dialogue of the deaf with the Indian government in the sense that they do not understand each other,” said Terry Milewski, veteran Canadian Broadcasting Corporation journalist. “The Indian government continues to insist that Canada should crack down on Khalistanis, take them out of the country, put them in jail or deport them. And the Canadian government continues to insist that, until they know what crime has been committed, they cannot do so. And the Canadian government is correct in saying so.” The onus is on India to provide concrete evidence to extradite the gangsters.

Milewski agreed that the Khalistani vote bank has captured some space in Canadian politics. “So there are two hurdles to cross; one legal and one political,” he said. “I am not saying whether they are guilty or not. Whether it is robbing a bank or blowing up a plane, they are against the rule of law. What is needed is strong and irrefutable evidence against them in western courts.”

India is aware of the roadblocks, and the NIA team led by director general Dinkar Gupta, a former top cop in Punjab, is busy making a watertight case against those accused in recent cases.

But besides getting its paperwork sorted, Delhi also needs to have smooth coordination with the Aam Aadmi Party government in Punjab. In fact, all political parties that have clout in Punjab have to come together to solve this problem.

The first line of defence against the terror network is the Border Security Force, which is adopting technologies to counter the drone menace. The second line of defence is the Punjab Police, which makes it even more important to have better coordination between central and state agencies. They also need to crack down on the hawala and other financial supply chains that fund the local networks.

“Curbing the drug menace was one of my topmost priorities,” former Congress chief minister Captain Amarinder Singh told THE WEEK. “We set up a special task force to fight this menace and we got good results. We broke the supply chain. We treated the addicts as patients and not criminals.”

Singh had a grouse with the AAP. “The incumbent government has undone everything we did,” he said. “I do not think they have come to grips with governance. I have seen reports suggesting that drugs are easily available in most parts of the state.”

In 2015, a survey, commissioned by the Union government, said Punjab had 2.32 lakh drug dependents. It led to a war of words between various political parties.

“The drug problem in Punjab is indeed serious,” said Dr Atul Ambekar, professor at the National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences. “In terms of proportion of people affected by drug addiction, Punjab figures among the top states for almost all categories of drugs.”

But there is hope. The state’s special task force and the health department have been drawing lessons from the de-addiction programmes of 32 countries, including Iran, which reportedly has the largest number of addicts.

Ambekar said the highest rates of opioid addiction were seen in states along the known international heroin trafficking routes (northeast and northwest). “Thus, it seems like control on legal opium cultivation, and on availability of low-potency opium products like bhukki (poppy husk), has been followed by a higher demand for internationally trafficked heroin,” he said.

Punjab is following a three-pronged strategy to reduce supply, demand and harm. It is increasing the number of de-addiction centres and Out Patient Opioid Assisted Treatment centres to avert deaths due to overdose. Unlike at a de-addiction centre, where the patients are denied the drugs, OOAT centres try to wean them off drugs by giving them tablets containing a lower dose. After Bhagwant Mann became chief minister, 320 new OOAT centres were added; there are 528 in total. “The OOAT clinics are helpful, especially for the poor who use traditional opioids like the husk of the opium plant or the most commonly used brown sugar and heroin (chitta),” said Dr Sandeep Singh Gill, senior programme officer of the de-addiction programme of Punjab’s health department. “The use of injections or adulterated forms of these drugs results in deaths or deadly infections like HIV or hepatitis.”

Latest figures (2022) show 8.62 lakh registered patients in de-addiction and OOAT centres across Punjab. This is a big spike, but it also means that more people are registering now, which is a good sign.

If militancy tore apart a generation of Punjabi youth in the 1980s and 1990s, the lure of drugs cost many others their lives in the last decade. Now, there seems to be a heady mix of the two, and the youth are more vulnerable than ever. The need of the hour is a social security model supported by a well-rounded approach by the Union government to keep the youth away from drugs and dons. It might be too late for the likes of Landa, but for the many teens in Punjab, there may yet be light at the end of the tunnel.

(Names of juveniles and their relatives have been changed for confidentiality.)