Happiness is a journey, not a destination,” said the Buddha, addressing humankind’s eternal quest for happiness. It would take 2,500 years for science to catch up with his wisdom. But in the 21st century, happiness seems to have a destination―Finland. It is the happiest country on earth, and has been for six years in a row.

Located on the northern fringes of Europe, Finland with a population of nearly 56 lakh, is small, dark and cold with long winters. What’s there to be happy about? The only thing the world knew of Finland was Nokia. The Finns are not the easiest to talk to. Summer is beautiful, but danger lurks in the form of mosquitoes the size of fighter jets. Still, Finland tops the United Nation’s Happiness Index.

No one is more surprised by this coveted honour than the Finns, who do not see themselves as the happy, hugging, laughing type. Says philosopher Frank Martela, “When Finland first topped the happiness ranking, we were sceptical. We thought there must be a mistake. Being the happiest doesn’t fit in with our self-image of being calm, unsociable, even melancholic.”

An enduring joke is about two Finns going to a bar for a drink. One says, “Cheers.” The other asks grumpily, “Have we come here to talk or to drink?” Says Merete Mazzarella, writer and professor of literature, “Look inside a Helsinki bus, the Finns look grimmer than most other people.” Choir singing is popular. “It is a good way for us to be social,” she says. “We don’t have to necessarily talk.”

The annual World Happiness Report is produced by the UN’s Sustainable Development Solutions Network. The rankings of national happiness are based on a worldwide ‘Cantril Ladder of life evaluation’ by Gallup, a global analytics and advice firm. Citizens are asked where they are on an imaginary ladder. The top rung rated 10 represents their best possible life and 0 their worst. Respondents can mislead, so the rankings are also anchored in solid social and economic data: life expectancy, social support, freedom to make life choices, generosity, absence of corruption and GDP per capita.

The Happiness Report followed widespread complaints against the GDP rating of countries’ progress, which fails to examine issues like environmental damage and social inequality. In 2011, the UN adopted the ‘happiness resolution’, aiming for “holistic development”. Bhutan that propagates ‘Gross National Happiness’ played a key role. Explains American economist and coauthor of the Happiness Report Jeffrey D. Sachs, “The main message is that governments contribute to happiness or misery. Our national leaders seek wars. They should be trained in happiness before they blow us all up. The world must return to ancient wisdom.”

So, what makes Finns happy? They enjoy the small pleasures of life, as ancient wisdom advocates. They love vacationing in their mökki, or summer cottages, relaxing with family and friends for weeks. There are 32 lakh cottages in Finland, most of them located in forests near one of the 1.88 lakh crystal-clear lakes that bejewel the nation. Says schoolteacher Katriina Apajalahti, “In many cultures, forest is a scary, dark place. For us, it is a refuge.” Almost 80 per cent of Finland is forests. A survey asked Finns where they felt safest, the overwhelming answer: in the forest.

Summer holidays are all about living a simple, rustic life, communing with nature without indoor toilets, electricity and running water. Says Finnish social scientist Roosa Tikkanen, “Nature makes us happy. We appreciate the silence, which is a big part of our culture.” Detox includes going offline and leaving behind the cares of the city. There is not much to do other than read and roam. Philosopher Bertrand Russell believed “a certain power of enduring boredom is essential to a happy life and is one of the things to be taught to the young. A happy life must be to a great extent a quiet life, for it is only in an atmosphere of quiet that true joy can live”.

Hiking in pristine forests, picking berries, plucking mushrooms, fishing in rivers, chopping wood, kindling fire, playing outdoor games, barbecuing freshly caught perch with porcini and washing it down with beer and vodka―this is Finnish heaven. Highpoints of summer days include sweating in their saunas, beating mosquito bites with birch branches, then swimming in the adjoining lake and finally sleeping like a baby on a wooden cot.

The sauna is to the Finns what church is to Christians. It is a sanctuary for contemplation, purification and socialising; a spiritual place for warming the soul and heating the freezing bones. It is a retreat to inhale the löyly―the hissing vapour rising from throwing water on heated stones. Sauna is listed as an intangible Finnish cultural heritage. In the old days, it was the haven where people washed themselves, babies were delivered, multigenerational family members―men and women, from the scampering to the doddering―gathered on Saturday nights to sit together the way they were born―stark naked. “When it is cold outside, it is wonderful to sit in a hot sauna,” says Mazzarella.

The word ‘happiness’ grabs instant attention, but is misleading, especially to the Finns. Happiness is relative, shifting, fleeting and flighty to be measured; but ‘wellbeing’ or ‘life-satisfaction’ can be. Sachs explains, “When researchers talk about ‘happiness’, they are referring to satisfaction with the way one’s life is going. It is not a measure of whether one laughed or smiled yesterday.” Finns are not vivacious, but they are content, with a quiet sense of wellbeing. Says Martela, “We are good in delivering services, not joyful emotions. But now people understand why we are number one. It makes sense.”

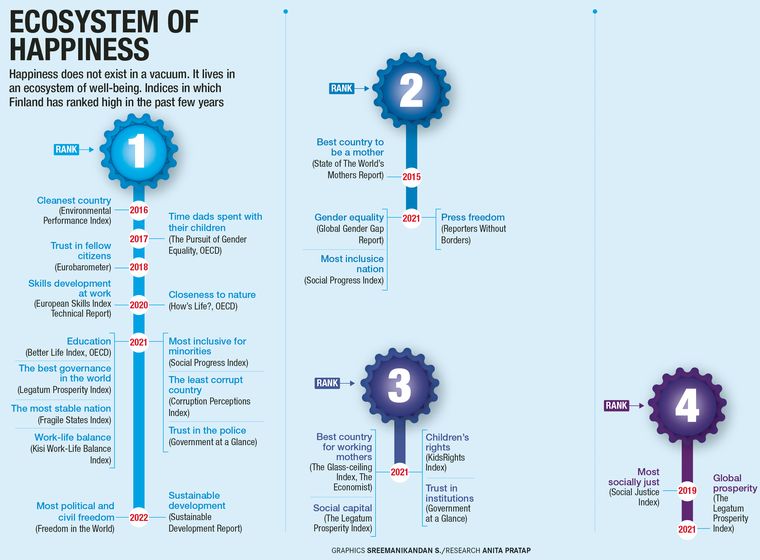

Finnish wellbeing is rooted in strong social support from family, friends and government. High GDP ensures a good standard of living―three-fourth of all Finns own their homes. Civic trust enhances comfort levels. The countries topping the happiness index have one thing in common―an ‘infrastructure of happiness’: the nuts and bolts of good governance that improve people’s lives. Norway, the richest Nordic country, invariably tops the UN’s Human Development Index, popularly known as the Quality of Life Index (Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland and Iceland are Nordic countries). Says Sachs, “Unlike America’s winner-takes-all system, the Nordic social democracy is a different kind of prosperity, a more equal and shared prosperity.”

Nordic countries are consistent toppers in the Happiness Index, even though they are neither the richest nor the biggest. In happiness, the US ranks 15, UK 19, China 64 and India 126. Says Tikkanen, “The Nordic model is well-known for taking care of its citizens from cradle to grave, we have no fear of injury, sickness or losing jobs. Education is high-quality and free, so everyone gets an equal start in life.” It helps that Nordic countries are rich with small populations, but then again several small countries are at the bottom of the happiness ladder. “Happiness is not a ‘soft’ or ‘vague’ concept. It depends on basic needs being met, good health, good citizenship, civic virtue and good habits,” says Sachs.

In his new book The Earth Transformed, historian Peter Frankopan highlights the role wellbeing plays in the rise and fall of empires: “In times of stress and collapse, the distribution of welfare has been key for a nation’s survival.” British economist Richard Layard urges governments to make wellbeing the central goal of public policy. New Zealand, the UAE and the UK are establishing happiness―more appropriately life satisfaction―ministries. Wellbeing is national security. It is also politics. The Happiness Report notes, “wellbeing is more important than the economy in explaining election results. Low wellbeing increases support for populism.” In Finland, too, the anti-immigration party won handsomely in the recent elections. But in the past, coalitions of even six disparate parties have ruled cohesively.

Finland’s stature as the happiest nation is remarkable, given its brutal past. From the 12th century, it was part of Sweden and then Russia in 1809. A vicious civil war raged in Finland between the reds and the whites―communists and bourgeoisie―in the 20th century. Russia bombed historic city centres and severed chunks of Finnish territory in World War II. Instead of airbrushing, Finns confront reality. They personify their map as Suomineito, the maiden with an amputated left arm. But Finland succeeded in converting history’s pain into modern gain, opting for post-war military neutrality and business with Russia. But Russia’s invasion of Ukraine changed public sentiments.” Says Mazzarella, “The invasion revived our historical memories of an aggressive Russia. It didn’t take a day. On February 25 (the war on Ukraine started on February 24, 2022), we Finns wanted to be part of NATO.”

The history of foreign interference forged Finnish nationalism, cemented also by a homogenous society. This has also led to charges of racism. Immigrants are fewer in Finland compared with Scandinavian countries (Norway, Sweden and Denmark). Located in the Soviet Union’s backwater, Finland was relatively isolated. Says Gunvor Kronman, CEO of Hanasaari, a Nordic cultural foundation, “Finland was poorer than its neighbours, so immigrants went to Sweden and Denmark for jobs. In fact, Finns themselves went to Scandinavia for work.”

Ancient wisdom from Aristotle to Buddha emphasised the need for civic virtue and good habits to be happy. The Finns rank high on civic honesty, trust, cleanliness and modesty. They do not brag or show off. Says Kronman, “We don’t flash wealth; it creates negative feelings between groups”. They are a close-knit community, bound together by Finnish, a difficult Uralic (non-Indo-European) language that no one else in the world speaks. So, they speak good English. Social media has certainly made Finns more social, especially younger women.

Thoughtful and self-critical, Finns admit their dark side. Among the Nordics, Finland has the highest suicide rate. Victims are mostly young men, who live alone and are reluctant to seek help. One reason is sun deprivation during the long dark winter that causes seasonal affective disorder (SAD), reducing the body’s neurochemical levels. Alcoholism is another. The authorities have implemented several successful measures, including the Sober Curious Movement to reduce alcohol consumption.

Literature contributes to shaping national identity. Unlike heroes who are superheroes in most mythologies, the Finnish epic Kalevala also depicts flawed characters. They perform noble exploits, but experience tragedy and humiliation, too. Instead of living up to impossibly high standards, there is a healthy realisation that life comes with defeat and dejection―for the mighty and the mortal. Realistic expectations contribute to happiness. All cultures have serious and lighthearted ways of looking at misery. A popular Norwegian saying is, “Happiness is good. But the misfortune of others should not be underestimated.” A popular Finnish proverb is, “Life is not a waiting room for better times. So just get on with it.” Finns value not heroism but sisu―doggedness when faced with adversity. It is not momentary courage but the ability to sustain that courage.

Finns tackle their problems with sisu. The whole society works towards a goal. After World War II ended, the state introduced the ‘baby box’, providing mothers with gifts for the newborn containing food, toys, diaper, creams, even outdoor clothes. Infant mortality fell. Mothers say how grateful they felt towards the government. Says former Norwegian ambassador to Finland Leidulv Namtvedt, “In the 1960s, we were all copying the crazy ideas coming out of Sweden, not the Finns. They were too poor to experiment. They focused on their two natural resources―forests and brains. They went about systematically building their society.” The Finns became rich and happy, content with berry-picking in summer and skiing in winter, keeping homes warm and enjoying hygge (popular Danish word for cosiness) with candles and cushions and flickering fires.

The Happiness Reports have spawned a full-fledged hygge industry, especially in the US, promising to unlock Nordic secrets with branded products, baked goods, life coaches, cute quotes, glossy books and activities like sweating saunas and ice swimming. William Davies’s book The Happiness Industry: How the Government and Big Business Sold Us Well-Being exploded the myth but did not dampen sales. But no ice or spice, berries or blankets, candles or cushions can fix the systemic causes of unhappiness, ranging from ill health, bad housing to poor wages―sorrows that governments can mitigate. The marketing bug has bitten even the Nordics, who use their ‘Luckyland’ status to tempt tourists into their honeytraps of happiness. Tourists welcome; immigrants, not so much.

The longest-ever scientific survey on happiness conducted by a Harvard team found the key to happiness lies in having close relationships. True. Modern rappers would distil Aristotle’s ancient advice, now proven by modern science: “Have Friends, Be Happy.” Environments contribute to happiness or misery. Happiness researchers have found some people have genetic variants making it easier to feel happy. Others are less fortunate. But the Finns show that lousy weather and grumpy genes can be overcome with grit and good habits.

At the structural level, the lesson Finland teaches is “build reliable, accountable, citizen-oriented institutions to provide people’s basic needs”, says Finnish diplomat Teemu Tanner. At the individual level, the takeaway is that happiness comes from leading a balanced life. An astonishing 90.4 per cent of Finnish respondents in the happiness survey said their lives were balanced. The Nordic ideal is not success but contentment, what the Buddha counselled and what the Swedes call lagom―enough.

Finns who have lived abroad believe the 20th century American dream of stable, prosperous lives is failing. Notes Tikkanen, “We do not have a culture of brutal competition. In America, it is extreme. People are always worrying, working late, getting sick, insecure, saving money for children’s college fees. Finns don’t have to worry about all this.” Sachs agrees, “Nordic countries prioritise balance, which is the formula for happiness. They are not societies that are aiming to becoming gazillionaires; they are looking for a good, balanced life and the results are extremely positive.” As British politician Ed Miliband famously said, “If you want the American dream, go to Finland.”

Pratap is an author and journalist.

THE MEASURE OF PLEASURE

How the World Happiness Report ranks countries

♦ The rankings are not based on an index, but on individuals’ assessments of their lives, and on one life-evaluation question in particular―rate your life on a scale of zero to 10

♦ The data is collected from nationally representative samples over three years

♦ Data on six factors are used to explain a country’s average life evaluation

THE SIX FACTORS

♦ GDP per capita (purchasing power parity)

♦ Social support: National average of binary responses―yes (1) or no (0)―to the question, “If you were in trouble, do you have relatives or friends you can count on to help?”

♦ Healthy life expectancy: How long people can live a healthy life, physically and mentally; derived from WHO data

♦ Freedom to make life choices: National average of binary responses to the question, “Are you satisfied with your freedom to choose what you do with your life?”

♦ Generosity: Derived from donations to a charity in one month

♦ Perceptions of corruption: National average of binary responses to two questions; “Is corruption widespread throughout the government?” and “Is corruption widespread within businesses?”

♦ In Finland, GDP per capita is a less significant contributor to life evaluation than in Denmark (rank 2) and Iceland (3). Residuals are the single biggest factor in the top-ranked countries. They are components over- or under-explained by the six factors

TEXT KARTHIK RAVINDRANATH