In 1995, Narendra Modi shifted base to Delhi from Gujarat after he was made the BJP’s general secretary (organisation). His reputation preceded him, as he had already won accolades for his organisational acumen, scripting victories in his home state. Modi would soon usher in a generational shift in the BJP’s collective thinking.

“We heard that he was very interested and well versed in technology,” said Manohar Lal Khattar, Haryana chief minister who was the BJP’s organisational secretary in the state when Modi moved to Delhi. “One fine morning, he came to us and asked us to take out three boxes from a vehicle. When unpacked, one had what looked like a TV. He told us it was a monitor. This was 28 years ago, when people hardly knew computers.”

At Modi’s instance, Khattar learnt to work the computer. He fed into it a wealth of party-related information, provoking questions of whether the entire party had been “captured inside it and its key thrown away”.

Those were the early days of information technology. Two decades later, Modi brought his fascination of technology to transform governance at the national level.

“Technology has become a powerful tool of empowerment to remove imbalance and promote social justice,” Modi said recently. “There was a time when technology was beyond the reach of common citizens and things like debit and credit cards were status symbols. But today, UPI has become a new normal because of its simplicity. Today, India is among the countries with the highest data use.”

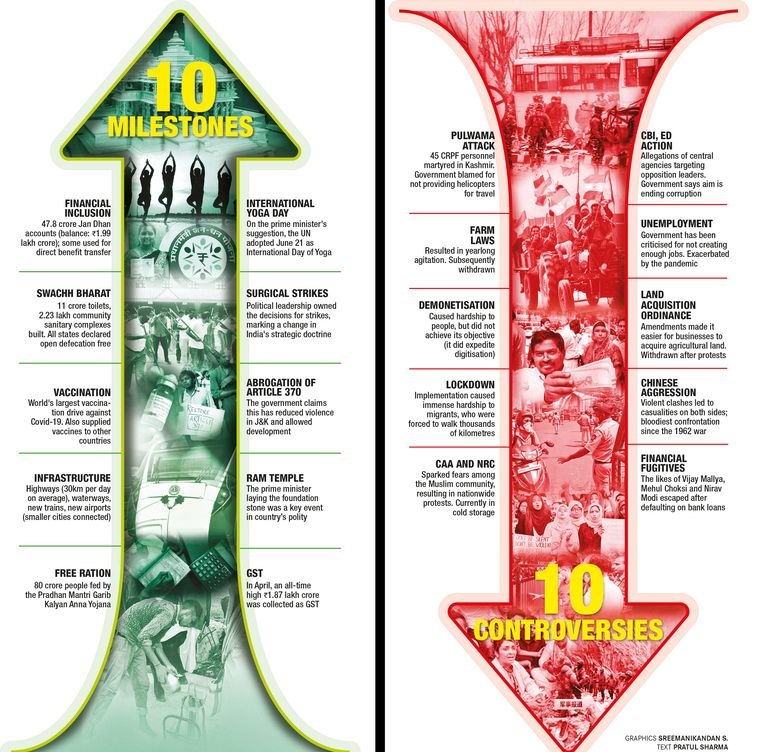

The use of technology has been the hallmark of Modi’s engagement with the people―from the party conducting its biggest membership drive, to the prime minister using social media to bypass traditional instruments of communication. Even the biggest benefit of the much-debated demonetisation in 2016 was rapid digitisation of financial transactions.

As Modi enters his 10th year as prime minister, he has already left his imprint on the country’s political history. He has forced a shift in how politics is practised and governance is delivered. The epochal changes of the past nine years have been foundational, with Modi making a conscious break from the past. He has left his mark on schemes that were initiated, and structures that have been built. Two of the most enduring such Modi-era structures are in Delhi―the new Parliament building and the brand-new exhibition-cum-convention centre at Pragati Maidan, where the prime minister will host G20 leaders.

What differentiates Modi’s legacy from those of previous prime ministers is his ability to bring in synchronisation between capitalism and socialism, the country’s two warring politico-economic streams. Modi has been able to dish them out from the same platform, without having to pay a political price for it. He has ensured ease of doing business, scaled up start-ups from mere 100 in 2014 to more than a lakh now, and empowered the industry to usher in changes so that wealth flows into the economy and wedded it with socialist-era welfarism through schemes for farmers, women, deprived sections and the poor.

“India is taking pride in following Indian growth models,” said Union Minister Bhupender Yadav. “Culturally, we have ushered in a process of returning to the roots. The nation is working with a ‘can do’ approach.”

According to Union Minister Kiren Rijiju, India’s global profile has grown. Leaders, he said, often ask him about India’s success stories in the fields of technology, manufacturing and social welfare.

In fact, Modi asks all corporate honchos from abroad calling on him about their plans to start manufacturing in India. “The prime minister is direct and focused,” said the CEO of a tech company after meeting Modi recently. “‘When are they going to start manufacturing?’ he asked. It is the only sound he likes. His knowledge is humongous even on everything technical.”

The experience the party has had in delivering governance has made the Modi years different from Vajpayee’s. “After our loss in 2004, we conducted a survey to study the reasons,” said Sumeet Bhasin, director of the BJP think-tank Public Policy Research Centre. “People had got roads and infrastructure, but in the survey they said they had not got anything. This time, the Modi government has put something in the pockets of everyone through welfare schemes. Even when infrastructure is being built―be it highways, roads and airports―there is people participation through many means, including programmes like MyGov. This shows this government’s connect with the people.”

Hailed as the strongest leader in decades, Modi has reaped benefits from his risky decisions. He risked his political capital by taking ownership of tough decisions like implementing demonetisation and lockdown, promising vaccination and buying Rafale fighter jets. The Balakot surgical strike was an even greater risk.

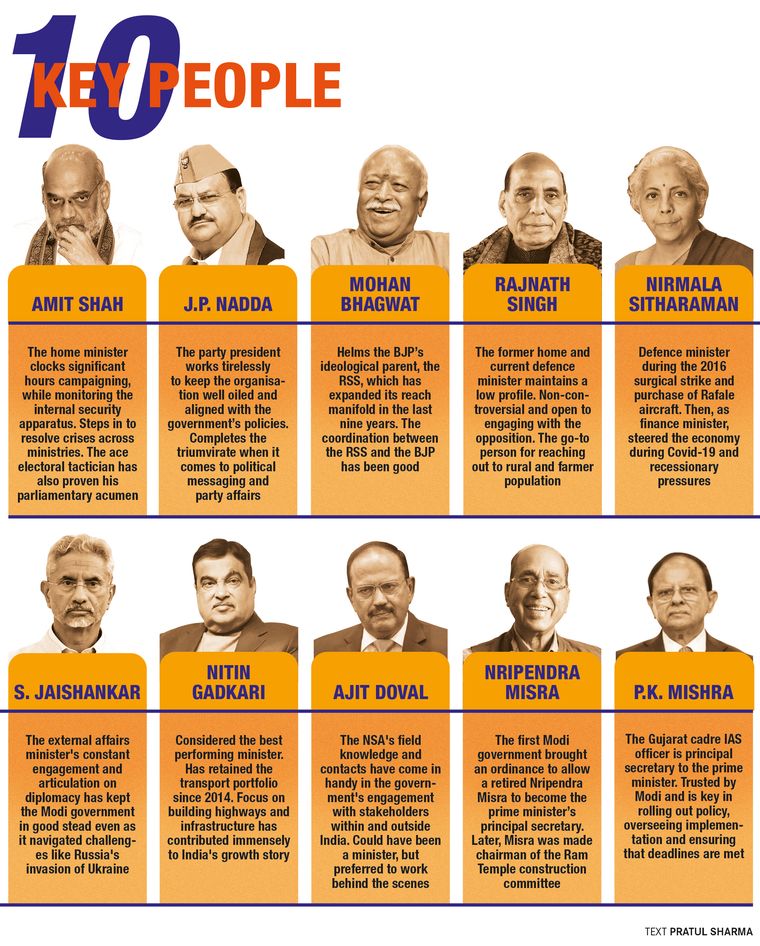

The electoral rewards have exceeded the risks. The party has firmly stood behind Modi in disseminating his message, acting as a bridge between people, him and his government. But what matters is not just the political message, but even the delivery of services. If Modi’s first tenure was marked by the rolling out of schemes, his second had a sharper focus on delivery. The second tenure witnessed greater reliance on technocrats like S. Jaishankar, Ashwini Vaishnaw, Hardeep Puri and R.K. Singh, who have all been focused on getting projects―both administrative and ideological―off the ground.

First as party president and then as home minister, Amit Shah has been a constant companion and trusted Modi lieutenant who delivered on political and ideological matters for the government and ensured that Brand Modi is not dimmed. That the Modi government won a massive mandate in 2019 was an indication of people’s trust in him despite niggling issues. The shift was in terms of delivering on the ideological agenda, be it abrogation of Article 370, building the Ram temple in Ayodhya, passing the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, or the efforts being made to bring in a uniform civil code.

The cultural iconography has also been brought to the forefront. The Ram temple, the Kashi Vishwanath corridor in Varanasi, the Mahakal corridor in Ujjain and Punjab’s Kartarpur corridor have blurred the fine line between state and religion, and made cultural nationalism an effective tool to communicate with the people.

In fact, Modi wears his cultural ideology on his sleeve when he engages with world leaders―be it in choosing gifts or taking them to country’s cultural spots. India’s soft power became an effective tool to enhance his image across the world. He shocked and awed the foreign leaders with his connect with the Indian diaspora, turning non-resident Indians into an instrument of diplomacy to engage with host countries.

On the national security front, the government prides itself in ensuring a tenure free of bomb blasts or major terror attacks. It has also scored on the external security front, but the issues with China remain a sore point.

One stringent criticism directed the government’s way has been the actions of the Hindu vigilante groups. Using aggressive hindutva as a political tool has meant that minorities have lost their heft and value as a pressure group. The action against opposition leaders are often cited as signs of witch-hunt.

“They have gone against all their promises, including ‘Sabka Saath, Sabka Vishwas’,” said Congress spokesperson and former diplomat Meem Afzal. “BJP office-bearers, ministers and sangh bodies have rallied against a particular community. They have succeeded to some extent. They won power for the second time on the same agenda, but it is finally phasing out. The way Rahul Gandhi took a stand, and carried out a national yatra against their ideology, it is being recognised.”

But the BJP differs, saying the creation of a welfare state is a watershed moment in the country’s history. “In these nine years, the Modi government has ensured that benefits of governance reach the last person in the queue,” said Sudhanshu Trivedi, Rajya Sabha member and BJP spokesperson. “Modi’s tenure has four dimensions. He has crafted a strong and robust economy, ensured internal and external security and, finally, restored national pride in everything.”

Now, as Modi enters his 10th year, there are a few red flags for him―economy, unemployment and the political messaging of double-engine government hitting a roadblock. Aspirations of young Indians have grown manifold, and a huge percentage of young voters who will cast their first vote in 2024 have no memory of previous governments. Also, the opposition has shown some signs of strategic thinking in taking on the BJP’s aggressive organisational machinery. Bread-and-butter issues may seem to triumph over the party’s cultural nationalism or double-engine government slogan, as it was seen in Karnataka and Himachal Pradesh. Freebies, handouts and the promised return to the old pension scheme could tilt the scales.

Economy has been one of the most debated subjects, particularly how the Modi government has handled it in the past few years. Modi has focused on capital expenditure as a way to rev up the economy and generate jobs and demand. It’s outcome will define Modi’s legacy in the years to come.

“The biggest achievement is the way Modi handled the economy post Covid,” said Gopal Krishna Agarwal, BJP spokesperson on economic affairs. “If one looks at international scenarios, the US is having difficulty as many banks are in crisis. We handled banking in a very strong manner through the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, the National Company Law Tribunal and the Benami Property Transactions Act. Post Covid, India’s infusion of liquidity was markedly different from how other countries handled it. The way we handled inflation and recession is also different.”

Also read

- 'India is confident, capable, uplifted and empowered': Ashwini Vaishnaw

- The making of a 'Modi'fied India

- 'India no longer sees itself as western-style democracy': Bhupender Yadav

- 'Modi's vision and determination is yielding positive results': Mahendra Nath Pandey

- 'India well on its way to achieve financial inclusion': MoS finance

- 'Other states have started following the Haryana model': Khattar

The finance ministry’s latest economic review painted a rosy picture. “There are downside risks to growth and upside risks to inflation, partly channelled through the external sector and partly originating from weather uncertainties,” it said. “Yet a strong point going India’s way is the strength of its domestic demand. Consumption has shown steady and broad-based growth, while investment in capacity creation and real estate is finding traction. April is too early to forecast the economic outcomes for the entire year. A good beginning, though, is a harbinger of positive outcomes.”

The economy may show signs of strength, yet the picture on the ground may not be as rosy. Rise in the prices of essential commodities has the common man struggling. “Macroeconomic parameters like inflation, recession and fiscal deficit that drive the economy are very strong in India in comparison with the three [top] economies of the world,” said Agarwal.

Winning a third term will put Modi on a par with the first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. Another electoral victory can provide further legitimacy and signal bigger steps.

Unlike 2019, the opposition is showing signs of strategic thinking. Regional parties recognise that if they do not pool in resources for the next elections, it may pose a crisis of credibility. The Trinamool Congress and the Nationalist Congress Party have lost their national party status. Mamata Banerjee of the Trinamool, Sharad Pawar of the NCP, Nitish Kumar of the Janata Dal (United), Arvind Kejriwal of the Aam Aadmi Party, and Mallikarjun Kharge and Rahul Gandhi of the Congress are holding parleys.

But will the united opposition stop Modi’s chariot?

“The signs were visible in Karnataka,” said Afzal. “Modi used the same language in Karnataka that he used in Uttar Pradesh. I think people are now tired. They know that this polarisation is being done to take the focus away from real issues. Modi may not be able to retain power in 2024 if a united opposition moves forward.”

Agarwal admitted that Karnataka was a setback. “But state and Lok Sabha elections are different,” he said. “The 2024 elections are about Modi and national issues.”

The BJP has already started holding review meetings in all states to iron out problems and ensure that Karnataka is not repeated again. According to Trivedi, the BJP may surpass its previous records in 2024.

Certainly, the next few months will be eventful for India. Modi will fight to save the legacy of his government, in the manner he has perfected in the past nine years. The opposition, even if united, would need new idioms and smarter slogans to stay in contention.