If Wagner fighters were asked to pick their weapon of choice, their now exiled boss Yevgeny Prigozhin would have probably chosen a sledgehammer. Last November, the group released a video showing one of its fighters in Ukraine, 55-year-old Yevgeny Nuzhin, getting his skull crushed with a sledgehammer by his comrades. His crime? He surrendered to the Ukrainians. Prigozhin released enough Ukrainian fighters to get Nuzhin back in a swap deal and ordered his execution. “A dog’s death for a dog,” he said. A few weeks later, the European parliament formally condemned the “heinous crimes” committed by the Wagner group, and Prigozhin sent the lawmakers a sledgehammer covered in fake blood.

Decades before he was feted as a ‘Hero of the Russian Federation’, Prigozhin had the opportunity to enjoy the state’s hospitality at a Saint Petersburg prison on multiple charges of violent robbery. He got out in 1990 after serving nine years, just as the Soviet Union was imploding. The streetsmart Prigozhin rose quickly through the subsequent chaos, launching a food business, befriending Putin―then a lowly official at the Saint Petersburg mayor’s office―and branching out into multiple lucrative enterprises. A decade and a half later, he emerged as one of the many oligarchs of Putin’s Russia.

WAGNER’S REAL BOSS

What triggered Prigozhin’s transformation from just another oligarch to one of Russia’s most powerful men was perhaps Putin’s decision to set up private military companies for “delicate missions abroad”. Back in April 2012, Putin told the Russian parliament that “PMCs could allow the realisation of national interests without state involvement”, offering plausible deniability.

While Wagner is often referred to as a private military company, no formal records exist to suggest that it is one. It was said to be founded by Dmitry Utkin, a lieutenant colonel of the GRU, Russia’s foreign military intelligence service. There are records of Utkin reporting to the GRU and the army, at least till 2015. The biggest Wagner barracks are located on a campus run by the GRU in Krasnodar district in southern Russia. Wagner units often use military aircraft, its members are treated at military hospitals and its arms and essential supplies come from the defence ministry. Even the passports used by Wagner operatives are issued on behalf of the defence ministry.

If there was still any doubt about who really owned Wagner, Putin put that to rest while addressing the nation after Prigozhin’s failed mutiny on June 24. “Between May 2022 and May 2023 alone, the Wagner group received nearly a billion dollars from the state. All of the funding the Wagner group received came from the defence ministry, from the state budget,” he said.

Wagner’s involvement in the 2016 American presidential elections using his troll farm called the Internet Research Agency offers another clue. “Prigozhin, on his own, was unlikely to be interested in Trump winning or losing. But Putin had a definite motive there,” said Natalia Kulinich, a Russian political observer based in Europe. She also pointed towards Wagner’s unusual recruitment methods. “Prigozhin could walk into any Russian prison and make his pitch to the most hardened criminals. He could offer them freedom, mocking the entire criminal justice system. It was possible because he was acting on behalf of the state,” she said. Wagner’s focus on foreign territories such as Syria, Venezuela, Libya, Sudan and Mali also allied perfectly with the interests of the Russian state.

WHY PRIGOZHIN HAD TO GO

When Putin launched his “special military operation” in Ukraine, Prigozhin was still a peripheral player. But a combination of factors―underwhelming performance by the Russian forces, unprecedented unity shown by the west and fierce fightback by the Ukrainians―resulted in a series of setbacks for Russia. It opened up an opportunity for Wagner as its hardened fighters gave Putin a few crucial wins, such as Soledar and Bakhmut. It also transformed Prigozhin into a frontline leader from a backroom operator as he openly criticised the Russian war strategy, badmouthed its leaders and became increasingly vocal about his leadership of the Wagner group.

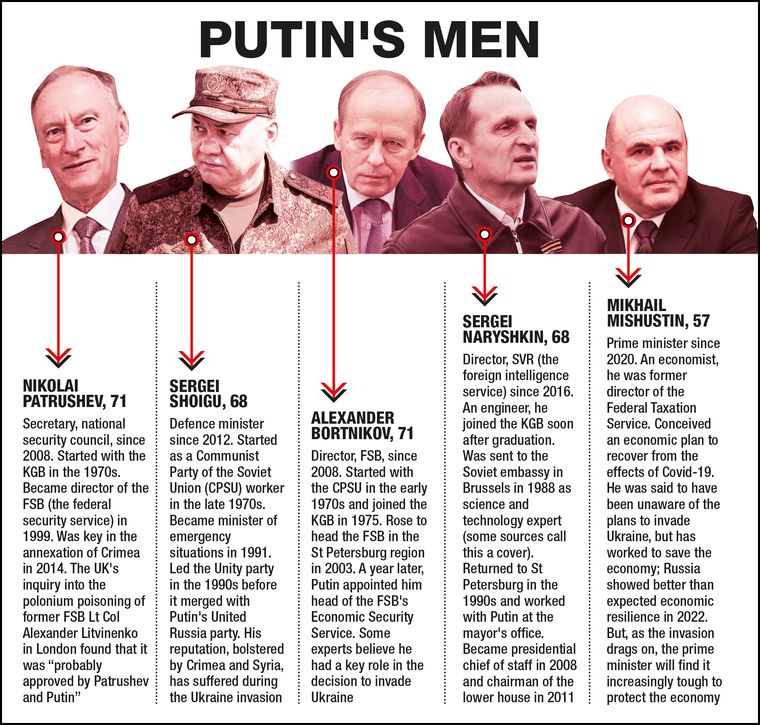

As Wagner’s profile started expanding, Prigozhin started asserting himself more. He put up billboards across major Russian cities, released television commercials and even advertised on PornHub. He also made some powerful enemies along the way―from Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu and Army Chief General Valery Gerasimov to Saint Petersburg Governor Alexander Beglov.

One of the videos Prigozhin posted on his Telegram channel showed a battlefield from Ukraine with the bodies of dozens of Wagner fighters. The camera was then cut to Prigozhin’s face as he yelled, “Shoigu, Gerasimov, you will eat their entrails in hell. Where is the fucking ammunition?” Coming from someone who once filed a case in a London court about suffering severe emotional distress after being outed as Wagner boss, it was a giant leap of faith. “Prigozhin was perhaps eyeing the defence minister’s post. With backing from certain sections of the military, he tried to appeal to the nationalist camp, which wants ruthless action in Ukraine,” said Anastasia Gornova (name changed), who works at a think tank. Although Putin encouraged some competition among his underlings to ensure that they would never be able to challenge him, Prigozhin’s antics were getting out of hand. And, to Putin’s annoyance, Prigozhin acknowledged his involvement during the American elections. So once Bakhmut was taken, Putin must have felt that Prigozhin outlived his utility and was no longer indispensable.

Unfortunately for Prigozhin, he was no match for Shoigu, a shrewd political operator who was a top-rung player even before Putin made his mark at the Kremlin. “The stage was set last year itself,” said Gornova. To begin with, Shoigu removed Dmitry Bulgakov, deputy minister in charge of logistics, who was close to Prigozhin. It cut off Wagner’s access to Russian supply lines. Prigozhin suffered yet another setback as Putin reappointed Gerasimov as the head of operations in Ukraine, replacing General Sergey Surovikin. Prigozhin shared an excellent rapport with Surovikin, known for his effective, but brutal tactics. After the failed mutiny, there were reports that Surovikin was detained, although he had put up a video message condemning Prigozhin.

Another major setback for Prigozhin was the ban on recruitment from prisons, which dried up the group’s most reliable source of manpower. The defence ministry now recruits prisoners directly. All existing Wagner mercenaries are asked to sign a government contract, essentially indicating a government takeover of the group.

Feeling cornered, Prigozhin tried to get Putin to intervene, but the president went with Shoigu and Gerasimov, forcing the Wagner chief to lead his troops on to Moscow. “Prigozhin’s objective was to draw Putin’s attention and have a discussion about conditions to preserve his activities―a defined role, security and funding. These were not demands for a governmental overthrow, but a desperate bid to save his enterprise,” said Tatiana Stanovaya, senior fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Centre. But it came to nothing.

A CHOREOGRAPHED REVOLT?

As Prigozhin’s resentment was well known, it is unlikely that his march to Moscow caught Russian authorities by surprise. “There may have been certain elements within the army which sympathised with Prigozhin and were opposed to the Shoigu-Gerasimov duo,” said Kulinich. “It explains why Rostov was taken easily and at least some of the Wagner troops could move quickly towards Moscow.”

But the manner in which the march fizzled out in a matter of hours showed that the authorities were prepared. “Putin knew about the mutiny in advance and so he could prepare to an extent,” a western official told the Financial Times. A Moscow-based analyst, who chose to remain anonymous, also concurred with this view. “The authorities reinforced the narrative that something major was happening. That is why they declared Monday (June 26) a holiday and dug up roads and even destroyed a few bridges. And it was given massive publicity. It was like creating the perfect backdrop to paint Prigozhin a traitor and discredit him,” he said. “On a weekend, it is difficult to find even a handyman in Moscow. But surprisingly, all these JCBs and excavators were ready, digging up asphalt and putting up roadblocks.”

While most western reports suggested that the march revealed Putin’s vulnerabilities, it was clear that he was in control. Moreover, the fact that Prigozhin was allowed to fly out to Minsk aboard his own aircraft hint at a staged mutiny. Ironically, the crisis enhanced Putin’s image, especially among the liberals who could hardly stomach the coarse and violent Prigozhin, and rooted for the president. Some observers even suggested that the mutiny and the response appeared to be the possible launch of Putin’s 2024 presidential campaign. Former CIA analyst Rebekah Koffler said the coup was staged to boost Putin’s political power. “He will eventually gain momentum, mobilise additional personnel and re-energise his offensive on Ukraine.”

What next for Prigozhin and Wagner

While Prigozhin appears safe at the moment, Putin could still change the terms of his deal with the Wagner boss if it suits him. His well-being depends on staying faithful to the conditions dictated by the Kremlin. Putin, in fact, left Prigozhin a warning in his speech. He said Prigozhin’s company, Concord Catering, was paid around a billion dollars for supplying food to army canteens. “I do hope that no one stole anything in the process or, at least, did not steal a lot. It goes without saying that we will look into all of this,” said Putin. Prigozhin’s mother, Violetta, is Concord’s registered owner.

On the other hand, if all goes well, Putin may even let Prigozhin back in and allow him to play some minor political role. He could be allowed to contest the next parliamentary elections as a candidate of some minor party propped up by the Kremlin. “He could make a comeback as a parliament member,” said the Moscow-based analyst. Similar things have happened in the past. For instance, Andrey Lugovoy, the former KGB agent who was convicted of murdering Putin critic Alexander Litvienko by polonium poisoning in London, was later elected to the parliament.

Also read

- Prigozhin death: Russian investigators confirm death of Wagner chief, 9 others in plane crash

- 'Talented; Man with difficult fate', Putin condoles Wagner chief Prigozhin's death

- Russia confirms Wagner chief Prigozhin was on crashed plane; flight data shows 'dramatic descents'

- Inside story from Russia: How Prigozhin built up his empire and got close to Putin

- Wagner group's international operations and war crimes

- What the Wagner imbroglio means for Ukraine

“Prigozhin’s control over the Wagner group, however, seems over,” said the Moscow-based source. “Wagner could get a new leadership or it could be absorbed by the state and its duties assigned to another group.” Within hours of Prigozhin’s banishment, deputy foreign minister Sergei Vershinin took a flight to Damascus to inform Syrian president Bashar al-Assad about the changes in the Wagner group. Similar visits were made to Mali, the Central African Republic and other hotspots where Wagner operates.

The behaviour of the Russian elite during the mutiny is also said to be under scrutiny. “Who said what and when is being examined. The travel plans of the elites are also being examined,” said Gornova. Investigative portal Vazhniye Istoril found out that the private jets of oligarchs Arkady Rotenberg and Vladimir Potanin as well as Industry Minister Denis Manturov left from Moscow’s Vnukovo airport when the mercenaries were on their way to the Russian capital.

PUTIN’S CHALLENGES

While Putin was successful in staving off the Wagner challenge, the veneer of invincibility which he has worked hard to project for nearly a quarter century appears diminished. Choreographed or not, the visuals of rogue soldiers marching to the national capital unchallenged is unlikely to help Putin’s image. More worryingly for the Kremlin, the nationalist camp of the “angry patriots” will be emboldened to demand tougher action in Ukraine, including tactical nuclear strikes.

Prigozhin was working hard to woo this constituency, railing against the elites’ children as “shaking their tails on beaches while the children of ordinary Russian families are dying”. It seems to have found great resonance among the families whose sons have been conscripted and sent to the front lines to fight a seemingly endless war. Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the exiled oligarch turned pro-democracy activist, was perhaps playing on this sentiment when he called, rather uncharacteristically, for a violent overthrow of the Putin regime. “We need to wake up to the fact that the fall of the Putin regime will not come about through the ballot box, but will require armed insurrection,” said Khodorkovsky after the Wagner march.

Rather surprisingly, Putin himself brought up the 1917 civil war analogy during the address he made to the nation when the rebels were marching to Moscow. It put him in the place of Tsar Nicholas II, whose disastrous leadership in World War I and the Russo-Japanese War of 1905 paved the way for the 1917 revolution, bringing to an end three centuries of Romanov rule in Russia. A year later, the tsar and his family were executed by a Bolshevik firing squad. Putin, an avid fan of the Russian imperial tradition, will likely have enough weapons in his arsenal to ensure that history does not repeat itself.