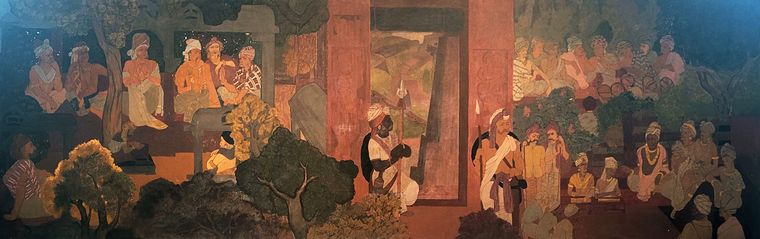

A few months before his samadhi, the Buddha was in Rajgriha (present-day Rajgir in Bihar), preparing to start his three-month rain retreat. He had an unexpected visitor―Vassakara, minister of King Ajatashatru of Magadha. The minister wanted the Buddha’s counsel on Magadha’s plan to annex Vajji, a neighbouring confederacy of republican tribal states.

But the Buddha did not answer Vassakara directly. He turned to his disciple Ananda and started a conversation that gave a peek into the republican governance system in the sixth century BCE. “Have you heard, Ananda,” the Buddha said, “that the Vajjians frequently hold public meetings of their clan?”

“Lord,” said Ananda, “so have I heard.”

“As long as the Vajjians meet so often,” said the Buddha, “and call public meetings of their clan frequently, may they be expected not to decline but to prosper.”

He then laid down seven conditions of welfare that the Vajjians were expected to adhere to: holding full and frequent assemblies, taking and implementing decisions in concord, preserving institutions, honouring elders, protecting women, conserving shrines and supporting the enlightened.

The message: the Vajjians should prosper as long as they met the conditions. Having received the Buddha’s counsel, Vassakara took leave after assuring him that Vajji would not be annexed―at least not in the near future.

The conversation, recorded in the Pali text Mahaparinibbana Sutta, moots a key discourse on polity. Scholars have wondered whether the Buddha’s advice ended up showing Ajatashatru a way to conquer the Vajjians, which he ultimately did more than a decade later as he expanded the Magadhan empire.

The seven conditions of welfare are often recognised as key governance principles that had elements of democracy. Buddhist monasteries adhered to the principles, which mirrored the ethos of the prevalent gana sanghas (clan-based oligarchies) of the time.

The leading republican state in the Vajjian confederacy, Lichchhavi, followed its own system of governance. Another text, Ekapanna Jataka, says Vaishali (the capital of Lichchhavi, in present-day Bihar) always had 7,707 ‘kings’ to govern the state. These kings belonged to the Lichchhavi clan and they were given to “argument and disputation”.

The Lichchhavi Gana Sangha had a number of administrative units, each of which was a mini state. They had an elected council, a general assembly that met once a year, and a system of voting that employed sticks. The ruling clans practised egalitarian traditions and rejected Vedic ones.

After the Buddha’s death, monasteries, too, followed a system of discussion and voting, says the Buddhist text Vinaya Pitaka. They had three systems of voting: the ballot, whispering in another monk’s ear, and show of hands.

Inscriptions on the walls of the Vaikunda Perumal Temple at Uthiramerur in Tamil Nadu, which has been dated to 920 CE, detail an elaborate system of local self-governance that elected councils by secret ballot. Similar inscriptions have been found in other parts of the state, indicating that an early form of democracy was prevalent in ancient times.

So, can India call itself the “mother of democracy”, as Prime Minister Narendra Modi phrased it while laying the foundation stone for the new Parliament building in 2020. Modi has since used the phrase multiple times―from his address to the United Nations in 2021 and his speeches abroad during official visits, to his radio show, Mann ki Baat. As India gets ready to host the G20 meetings in September, the invite says, “Welcome to the Mother of Democracy.”

The phrase gives a cultural and nationalistic interpretation of India’s ancient history. The UN’s adoption of the International Day of Yoga was a soft-power success that helped India maintain its position as “vishwaguru”. The ‘mother of democracy’ tag now places the country in the front row of world powers which have been employing cultural history in their quest for dominance.

The Chinese use their culture, along with their economic prowess, to present China as the dominant cultural civilisation. The US prides itself on being the world’s oldest modern democracy that has been thriving for more than 200 years.

The Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR) recently took Modi’s cue to come out with India: The Mother of Democracy, a book of 30 essays that detail the presence and evolution of democratic traditions in India over the ages.

The book covers a lot of ground―the sabha and samiti of the Vedic period, the gana sanghas, Kautilya’s Arthashastra, republican leanings of the Kakatiyas, Kashmir under Sultan Zain-ul-Abdin, the bhakti tradition of the Deccan, local self-governance in Tamil Nadu, Buddhist democratic ideals, democratic traditions of Namdharis, Bhils, northeastern tribes and Haryana’s khap panchayats, and continuation of the panchayat system under the East India Company.

“India is the largest democracy in the world and we Indians are also proud of the fact that our country is also the mother of democracy,” said Modi while talking about the book in the January edition of Mann ki Baat. “Democracy is in our veins, it is in our culture. It has been an integral part of our work for centuries. By nature, we are a democratic society.”

Modi said B.R. Ambedkar, chairman of the committee that drafted India’s Constitution, once compared the Buddhist monks’ union to the Indian Parliament. “He described [the union] as an institution where there were many rules for motions, resolutions, quorum, voting and counting of votes. Babasaheb believed that Lord Buddha must have got inspiration from the political systems of that time,” said Modi in Mann ki Baat.

The concept of democracy as a political system goes back to ancient Greece, particularly Athens. Cleisthenes (508-507 BCE), the father of Athenian democracy, introduced a system where all male citizens had equal political rights, freedom of speech, and opportunity for political participation.

The Athenian democracy had three separate institutions―the ekklesia, a sovereign governing body that wrote laws and dictated foreign policy; the boule, a council of representatives from the ten Athenian tribes; and the dikasteria, popular courts in which citizens argued cases before a group of lottery-selected jurors. The Athenian democracy survived for only two centuries.

In India, two millennia of rule by powerful empires uprooted previous concepts of democracy. The colonial powers who followed floated the idea of oriental despotism, a concept popularised by the German sociologist Karl Wittfogel.

But new archaeological and historical findings at the turn of twentieth century gave rise to several nationalist historians such as K.P. Jayaswal, A.S. Altekar, D.R. Bhandarkar and R.C. Majumdar. They talked about ancient republics and democratic societies. Jayaswal’s Hindu Polity, Majumdar’s Corporate Life in Ancient India, and Altekar’s State and Government in Ancient India shed new light on the gana sanghas, Vedas, Buddhist sanghas and local self-governance in Tamil Nadu of ancient times. It prompted a wave of nationalism as India was still under British rule. The discovery of Kautilya’s Arthashastra in 1906 also aided the nationalist project, which came to question the western notion of democracy that had Athenian democracy as the starting point.

“Most of the oldest civilisations have either died or are in museums,” ICHR chairman Raghuvendra Tanwar told THE WEEK. “Ours is the only surviving one, where linkages can be seen for 10,000 years.”

Critics, however, point out that India did not have developed systems of democracy, as decision-making in ancient republics such as Lichchhavi was a privilege of the ruling clans. Wealth and caste played a factor.

Tanwar says it is important to understand the essence of what ‘mother of democracy’ means. In Rajtarangini, a 12th-century account of the history of Kashmir, author Kalhana talks about how kings should be: “He should be dispassionate and fair, and should not take sides.”

During the Vedic period, kings took oath that they were committed to the common good and welfare of the poor. “Vedic literature, for example, talks about the presence of sabha and samiti, from which kings drew their power,” said Tanwar. “We told the world that you don’t escape actions. In the broader sense, this is precisely what democracy should be, meaning that you cannot escape the course of your actions.”

The ICHR book projects Harappa as an example of an early democratic institution. According to Vasant Shinde, archaeologist and former vice chancellor of Deccan College, the concept of democracy and welfare state can be traced back to the Harappans. He says archaeological evidence of well-planned Harappan cities indicates that they had an administrative system similar to today’s panchayats.

“Unlike Egyptians who built pyramids, the Harappans did not build imposing structures that served no purpose for ordinary people. Instead, they used their wealth to create clean, well-planned civic amenities,” said Shinde, who headed the recent Harappa-related excavation at Rakhigarhi in Haryana.

Apparently, the Harappans were able to collect tax efficiently, provide clean and hygienic water to residents, and build public granaries. “It would not be farfetched to surmise that all these facilities were created on the instructions of a group of administrators, like modern-day panchayat members, who were likely chosen by the populace,” said Shinde.

According to him, the administrators had a slightly higher status in Harappan society, as indicated by the fact that they had spacious, independent residential units in the citadel area of the city. All available evidence affirms the existence of a democratic system during the Harappan period, which dates back to about 4,500 years ago.

Ideas of participative governance come from the Vedas as well. The Rig Veda and Atharva Veda talk about sabha and samiti. Jayaswal argued that a samiti was a sovereign body from the constitutional point of view, while sabha was a standing body of selected men working under the authority of the samiti. The terminology is still prevalent.

Grammarian Panini talks about presence of janapadas (republics); Arthashastra identifies sanghas and ganas; and Pali texts translated by Buddhist scholar T.W. Rhys Davis reveal a society that took decisions after convening assemblies. Greek records and travelogues of Arrian and Megasthanes also attest to the existence of republics in ancient India.

The gana sanghas had kings as the head of the executive, but the kings did not enjoy absolute power. There was a council of ministers, comprising members of the ruling clan. Apparently, the Malla republic had four members in its council, while Lichchhavi and Videha republics had nine and 18 members, respectively.

In Lichchhavi, disputes regarding matters of war and religious and social issues called for voting. If consensus proved elusive, a committee called udayvahika was appointed. There were four voting techniques―open voting, secret ballot, mouth-to-ear whispers and the “evident system”, in which names of other voters were declared. There were seven types of courts as well, with the king heading the judiciary. Lichchhavis had presidents (ganapati), vice presidents (upa ganapati), army chiefs (senapati), ambassadors and other key heads of administration.

Inscriptions found in Tamil Nadu shed light on the rules governing these ancient republican societies. A slab discovered at the Bhaktavatsala Perumal temple at Thirunindravur has rules of the judiciary. Artefacts found at a temple at Mannur specify the criteria for selecting judges. Apparently, temples acted as social institutions and public meetings were held in their mandapas.

Also read

- Independence Day 2023: Key points from PM Modi's speech

- 'Country is with Manipur': PM Modi in I-Day speech

- PM Modi greets citizens on Independence Day

- What history tells us about self-governance in ancient Tamil Nadu

- Ancient Buddhista sanghas: From dhamma to democracy

- Lichchhavi: A republic for oligarchs in ancient India

Inscriptions dated to the rule of Chola king Parantaka-I have information on the criteria for electing members of different committees. Proficiency in Vedas and Vedangas was necessary, and the members were selected by lot (kudavolai). They held office for a fixed term and were not eligible for reelection, so that others could have the opportunity to serve.

As colonial administrator Charles Metcalfe wrote in 1830, Indian villages survived centuries of rulers and ruling systems. “The village communities are little republics,” he wrote. “They seem to last where nothing else lasts. Dynasty after dynasty tumbles down, revolution succeeds revolution… but the village community remains the same.”

Another example of democratic ideals in medieval India is the Anubhava Mantapa, established by 12th-century social reformer Basavanna in present-day Karnataka. The Anubhava Mantapa was a platform for people of diverse backgrounds to engage in open dialogue, share their experiences and ideas, and contribute to the advancement of knowledge. The body was inclusive―there was no discrimination on the basis of caste, colour or gender.

Billed as an academy of mystics, saints and philosophers of the Lingayat faith, it still finds resonance in present-day Indian politics. The new international convention centre for G20 meetings at Pragati Maidan in Delhi was recently christened ‘Bharat Mandapam’. “The Anubhava Mantapa―often referred to as the first parliament of the world―represents a democratic platform for debates, discussions and expression of ideas,” said Modi while inaugurating the centre on July 26. “Today, the world acknowledges that India is the mother of democracy. From ancient inscriptions found in Uthiramerur, Tamil Nadu, to places like Vaishali, India’s vibrant democracy has been our pride for centuries.”

No reference to democracy in India can be complete without referring to the drafting of the Constitution. As many as 389 members spent more than 1,000 hours over 166 days―roughly, 149 million work hours―to draft the Constitution.

“A key feature of India has been the ability to involve individuals in the tasks of governance, irrespective of primordial identities based on family, language, caste, colour and religion,” said M. Rajivlochan in his essay in India: The Mother of Democracy. “This differed from the western notion of democracy that was predicated on a model of power-sharing between groups. In India, the individual was the centre of all such norms…. In 1928, when the Nehru report created first draft of the Constitution, it focused on individuals and not political parties. It deliberately avoided any reference to parties or partisan groupings. In free India, individual would remain the focus of all norms.”

The Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts has created a website on India as the mother of democracy. It highlights the egalitarian views of bhakti poets and mystics like Lal Ded, Kabir, Guru Nanak, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, Srimanta Sankerdev, Guru Ravidas, Sant Dyaneshwar, Bulleh Shah, Tukaram and Poonthanam Nambudiri, the traditional councils of tribes in the northeast, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, the “world’s oldest democracy” of Malana village in Himachal Pradesh, the tenures of rulers such as Ashoka, Akbar, Suheldev and Shivaji; and empires such as Vijayanagaram, where democratic ideas were practised.

The question is: how resonant are these ancient democratic traditions today? The answer, perhaps, lies in the warning that Ambedkar sounded. “A time may come,” he said, “when we may get so fed up with the vagaries of democracies that we may only want democracy for the people, and may not be bothered whether it was of or by the people.”

Clearly, ancient India tells us that there is more to democracy than mere elections.