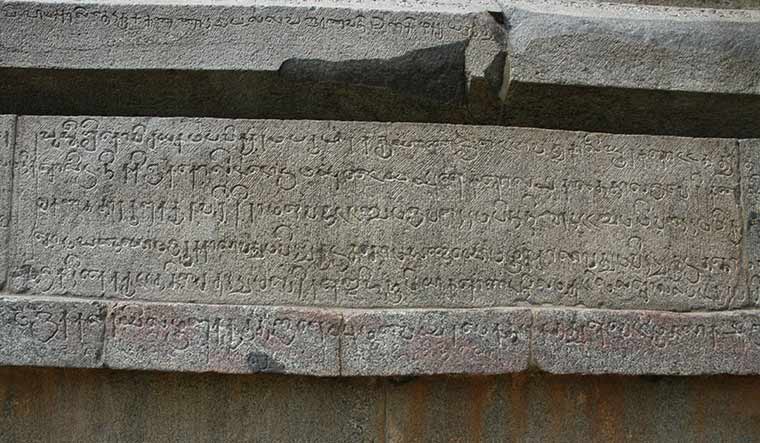

SANGAM LITERATURE, especially the anthology of classical poems Purananuru, shows that ancient Tamil Nadu had a form of self-government. Inscriptions found on a temple wall at Uthiramerur, dated to 920 CE, have shed light on how villages governed itself during the rule of Chola king Parantaka I.

The villages elected committees whose members held office for a year. After their tenure, they could not be reelected for three years. Committees met in the halls and premises of temples.

Even as the kings wielded political power, administration at the village level was decentralised. Village committees handled all matters related to land, irrigation, taxation and gold, with another committee that met annually overseeing administration.

Also read

- Independence Day 2023: Key points from PM Modi's speech

- 'Country is with Manipur': PM Modi in I-Day speech

- PM Modi greets citizens on Independence Day

- I-Day special: The fascinating history of India's ancient democracies

- Ancient Buddhista sanghas: From dhamma to democracy

- Lichchhavi: A republic for oligarchs in ancient India

Each village was divided into 30 wards to ensure fair representation of the local population. Elections were held using palm leaves that had names of candidates written on them. Only educated and reputable tax-payers aged between 35 and 70 years were allowed to contest polls. Relatives of serving members were excluded.

Elections were held in the presence of everyone. Leaves would be deposited in a ballot pot kept in the middle of the gathering, and a young boy would take them out after polling and hand them over to an election officer. Names written on the leaves would be read aloud until all votes were counted.

Many inscriptions about such systems of self-governance have been discovered in Ukkal, Manur, Tirunindravur, Kaveripakkam and Palayaseevaram in Tamil Nadu, Thirubhuvanai in Puducherry, and Bagur in Karnataka.