Virginia House no longer smells of tobacco. Rather, it smells of fragrant agarbattis. What once housed the cigarettes of W.D. & H.O. Wills is now the home of milled atta, baked cookies, incense sticks and more.

The big daddy on the cigarette block, ITC realised it was but just a wanna-be kid when it entered categories like biscuits and atta (wheat flour) in 2002. It was surrounded by well-entrenched top guns of the FMCG sector (fast-moving consumer goods, a term used to describe products ranging from soaps and snacks to flour and floor cleaners)

―from global giants like Unilever, Nestle and P&G to homegrown players like Dabur and Parle. The writing on the wall was clear. The company had to do something drastic and dramatic if it had any hopes of surviving, let alone dominating, the segment.

“In a globalising marketplace, you cannot compete unless you bring something unique to the table,” said Sanjiv Puri, chairman and managing director of ITC Ltd. While planning its ambitious foray into biscuits, strategy sessions at Virginia House, the colonial building on Kolkata’s Chowringhee Road (now officially Jawaharlal Nehru Road) that housed its corporate headquarters, were clear: in a market dominated by household names like Parle and Britannia, you need to break the clutter. But how?

“We started innovating from the beginning. Our first Marie (tea biscuit) was an orange one!” said B. Sumant, currently ITC’s executive director and back then part of the team that launched snacks. “We had an orange Marie, a regular Marie, and then we came up with an oats Marie. We were the only ones I knew till date having an orange Marie and an oats Marie!”

The orange Marie might not have taken off, but it sure garnered enough attention to get ITC its toehold in the hypercompetitive biscuit business. It soon followed it up with the first-ever ‘centre-filled’ cream biscuit with its Sunfeast Dark Fantasy line. While cream biscuits in India until then were sandwich cream between two pieces of biscuit, ITC brought in technology from Denmark to fill cream within the cookie. The result? Dark Fantasy shot to leadership in the premium cookie space, and has stayed put there since then.

“The aspiration has always been about leadership,” said Puri. “Not merely by size or profitability, but also about leadership in the quality of the service or the product that we deliver. That is what we have worked on in the past few years. And, of course, that has seen us define what we call ITC Next.”

FUTURE IS CALLING

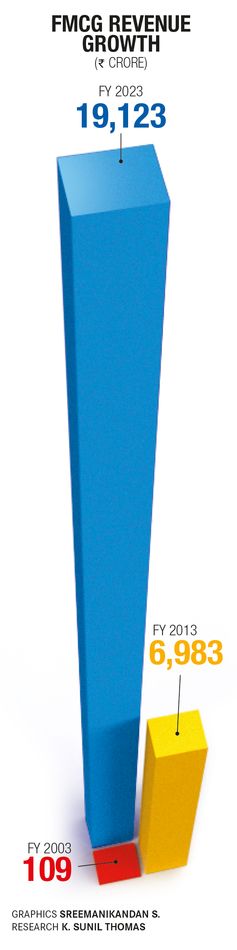

ITC Next is Puri’s next-gen transformation philosophy to make the gargantuan company ‘agile and future-ready’. That may sound surprising considering the fruits of success it has just about started enjoying after years of patient, often painful, transformation by diversifying from its core cigarette business to snacks, soaps and shampoos.

It was the kind of success most corporate giants can only dream about. ITC is now the third most valuable tobacco seller in the world, and its stock now consistently beats the Nifty average, growing nearly double that of the index which grew 20 per cent. In its latest quarter results announced earlier this week, ITC reported a standalone net profit at Rs5,572 crore, registering a growth of 11 per cent from the same quarter of the previous financial year. The results beat street estimates. The hotels segment witnessed its best-ever quarter, with revenue increasing by 18 per cent and profit before interest and tax increasing by 57 per cent.

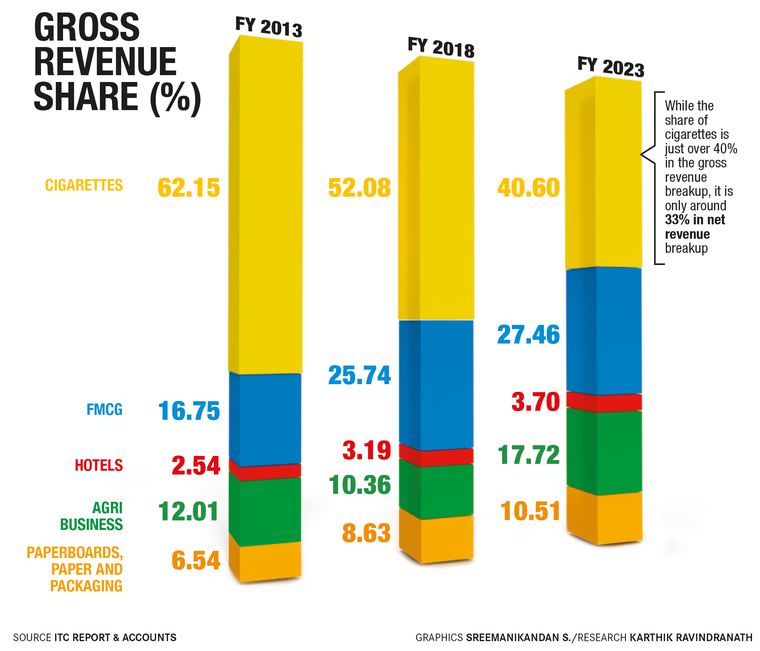

What is reassuring, particularly to the executives at Virginia House, is that the push to diversify beyond the ‘sin’ business of tobacco has worked out pretty decently. Non-cigarette business now makes up about 67 per cent of the total revenue, and is way more than revenue from tobacco products that used to be the top category for the longest time.

Even better, ITC has not only managed to turn profits in many of these forays, but also raced to the top of the pile. Aashirvaad, its atta brand, is probably the largest selling in the world―it is exported to some 65 countries. ITC also holds pole position in categories as disparate as cream biscuits (Sunfeast), snacks (Bingo!), notebooks and stationery (Classmate) and incense sticks (Mangaldeep).

“ITC has undergone humongous change,” said Harish Bijoor, FMCG veteran & brand and business strategy specialist. “I don’t call it a non-cigarette company, but a more than cigarette company. FMCG is a big, big play. You are talking turnovers upwards of a hundred thousand crores eventually. And if Sanjiv Puri has his way, he will do it.”

But how did a company that focused on cigarettes and tobacco for nearly a century make that pivot into areas as disparate as biscuits, packaging and hotels? What is the logic behind going in for these seemingly unconnected areas?

METHOD IN THE MADNESS

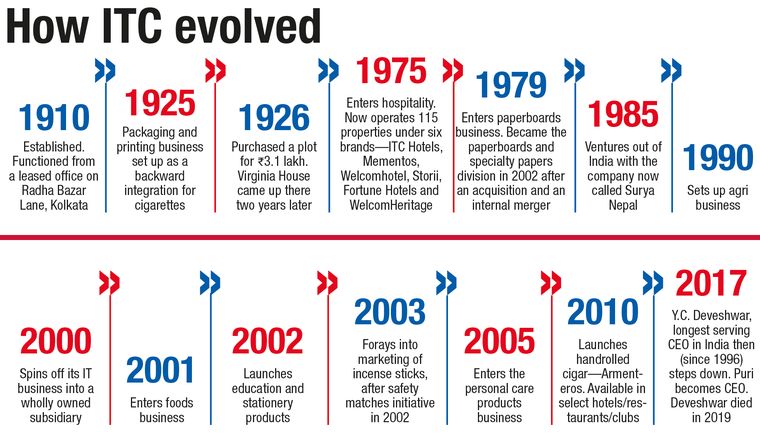

For long ITC was content with its hugely successful cigarette and tobacco business and its iconic brands like Wills Navy Cut and Gold Flake. The only other forays during the licence raj era were into hotels, agriculture and paper & packaging, which, in more ways than one, complemented the cigarette business.

However, as liberalisation flung the market wide open, it brought in two big worries to Virginia House’s doorsteps―one, international biggies flooding the cigarette market, and two, more important, the decelerating cigarette consumption owing to heavy taxation and public campaigns against smoking. “Clearly the objective was to create multiple drivers of growth that leveraged our strengths,” said Sumant. “We needed an alternative engine of revenue and profitability to cigarettes.”

That was when the decision was made to diversify into areas like FMCG as well as into fashion (Wills Lifestyle and John Players, which was a short-lived experiment), personal care (Fiama and Vivel) and more.

As Bijoor put it, “there is a method to the madness at ITC”. While paperboard or agriculture or even the ‘Kitchens of India’ brand which sold tinned supermarket version of the famous Dal Bukhara from ITC Hotels may seem they have no connection with each other, they, in reality, do.

“To be successful, you have to be able to leverage the synergy of a diversified organisation,” explained Hemant Malik, executive director in charge of ITC’s food business. “We started thinking, what are the strengths that hotels bring? What are the strengths that paper and packaging bring? That distribution brings? The knowledge of tobacco and farming and agri? And we put all of that together.”

ITC’s strong presence in the agri business and the e-Choupal network, which linked thousands of farmers and helped it scale up sourcing for its packaged foods venture, significantly contributed to its biggest success in the non-cigarette portfolio―Aashirvaad atta. The experience of the chefs at its popular hotel restaurants came in handy when it developed biscuits, chips, chocolates and frozen foods.

For instance, when Bingo! introduced Mad Angles, ITC hotel chefs tested 32 different gravies to dip the potato chip into, to see which masala will work. Mad Angles stood out not just for its triangle shape, but also its flavours. There were two options even for the tomato flavour―a (continental) ketchup flavour and another one leaning towards (desi) chutney.

“We had to differentiate ourselves to get attention and to break through; so that became part of our DNA, that is how we grew business in every category,” said Sumant. “Our rule was to have a better and differentiated product than what is there. Many of these have gone on to become blockbusters.”

Behind the scenes, the vast network of distributors ITC’s cigarette business had developed across the country played a crucial role. “The choice of FMCG was very clear because with cigarettes we had established a distribution network across the country in the most remote of places,” said Sumant. “It was a great way to distribute fast moving consumer goods as well.”

Today, ITC’s brand building spree is unmatched. It launches around 100 new products (including sub-categories) every year, a pace maintained even during the lockdown. Such rollout is enabled by its research and innovation centre in Peenya in Bengaluru, where every category of product has its own mini factory, helping the company come up with new products based on market research and insights from its Sixth Sense data centre that monitors online chatter.

BYTING INTO THE FUTURE

Getting bigger and bigger might be good for your bottomline, but it comes with its own baggage―coordinating disparate divisions and a workforce of nearly 50,000 people, and still remaining agile and nimble to take on future challenges. Puri believes ‘ITC Next’, with its emphasis on embracing digital and going sustainable, is the answer. “We see digital and sustainability becoming mega trends in the next decade,” he said. “Therefore, in our whole philosophy of growth, anything that is aligned to them is a priority for investment.”

While most other big businesses look at digital more as an avenue for sale or cost cutting, ITC has seamlessly incorporated it into its chain of operations―right from a farmer in a remote village using the new version of e-Chaupal called MAARS (Metamarket for Advanced Agriculture and Rural Services), Zen for supply chain planning, and Pace for the salesforce and UNNATI, an app for retailers to place orders.

For instance, an artificial intelligence engine crunches data of a kirana store to see what the retailer is ordering to anticipate future demand. “We subscribe to a lot of other data as well on socioeconomic indicators,” said Sumant. “Are there ATMs in that small village? What is the average income? What are the rental values? We use our own transaction data and other data feeds to decide what is the potential of an outlet.”

For the consumer, there is the itcstore.in, even though ITC’s distribution muscle means its products are available across the spectrum, from corner stores to hypermarkets to quick commerce platforms. As the skew of digital sales increases, ITC could well be that super app that finally clicks with Indians. “If there is one company in this space which has the ability to make a killing out of a super app, it is ITC,” said Bijoor.

THANK U, NEXT

The big news at ITC in 2024 will be its much-awaited hiving off of the hotels division into a separate company. However, inside Virginia House, the work will be equally frenetic on other growth areas.

“Categories of the future I have in two buckets,” said Puri. “One is which I am scaling up and the other one I am incubating. Scaling up categories like frozen snacks, beverages and Nimyle floor cleaner. What I am incubating are segments like chocolates and Dermafique, our premium skincare brand.”

But that is all he would say, as he would like to keep the cards close to his chest. Of course, ITC is intent on expanding beyond the borders―besides an existing joint venture in Nepal and a hotel set to open in Sri Lanka in March (its first outside India), the conglomerate is opening subsidiaries in what Puri calls ‘adjacent markets’.

Bijoor believes the home supplies category itself presents immense scope for expansion. “Within the kitchen, there are 46 terrains―these numbers are exact because I have done a kitchen audit in terms of FMCG to determine how many different brand spaces exist. And they have got into just eight so far,” he said. “There are drawing room needs, from a mosquito coil to a bulb; there are bedroom needs; there is a puja room they are already in, with their match boxes and agarbattis. The kitchen is only a toehold into the house. Once the toe is in, the foot will be in, and once the foot is in, the leg will be in. The ITC body obviously aspires to occupy the entire home.”

ENDURING VALUE

For all his company’s shining successes in the present and sweeping ambitions for the future, Puri knows well enough not to lower his guard. Hiving off hotels will free the parent company of a cash-guzzler that is slow in giving back, but challenges remain for divisions like paperboards and packaging that are facing the onslaught of Chinese products, and the agri business that often gets caught in regulatory headwinds during procurement.

Then there is FMCG. Aashirvaad and Sunfeast were runaway successes, and Savlon did well during the pandemic, but ITC still needs to cover a lot of ground when it comes to other categories where rivals like Unilever (Lux, Surf), Reckitt Benckiser (Dettol), and Procter & Gamble (Head & Shoulders, Gillette) have a strong presence in. “If you want to build profitability for the FMCG business, you will have to build strong brands in the personal care and home care space, too,” said Jeevan J. Arakal, professor and chairperson of branding & PR at T.A. Pai Management Institute, Manipal.

Like every other FMCG player, ITC is targetting the booming beauty market as well with its Dermafique brand. Taking on specialised players like L’Oreal and Nivea, however, is not easy. “It is a profitable category, but distribution challenges are different and the branding support that you will have to give is different. So this is a long-term play,” said Arakal.

As it gets bigger, ITC will come in the crosshairs of not just rival FMCG companies, but also fellow desi players backed by a conglomerate like Tata Consumer and Reliance Retail, who are also hungry for growth. ITC’s ace up the sleeve here could well be its huge capital reserves, massive and expanding distribution network, and perhaps more important, a leadership team that is in it for the long term. Said Arakal: “As they make these big corrections and big changes, I would say that this is a company with a very strong long-term orientation, which is reflected in the kind of investments they are making.”