Lights dim in Dongri, the bustling port town in Maharashtra that was once home to smuggler-gangsters Karim Lala, Haji Mastan and Dawood Ibrahim. As crowds leave the market streets, shutters are rolled down and gunnysacks are heaved into cars, carts and two-wheelers.

Sleuths of the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence make frequent visits to the deserted alleys at this hour, hoping to stumble upon consignments of gold, that might have escaped the airports and seaports of the financial capital. In January alone, the Mumbai airport customs seized gold worth more than Rs3 crore in different cases―gold wired in trolley bags and inner wear in flights from Jeddah, and gold dust from Dubai. The identity of the suppliers and whether the gold was meant to be sold in shops dotting Dongri have become a matter of investigation.

What the customs caught is just a drop in the ocean. Dongri made a rude comeback on the smuggling map in 2019 as the melting pot for smuggled gold from around the globe. In April that year, as much as 4,522.75kg gold worth Rs1,473 crore was seized from just one Dongri-based syndicate. It was the largest such cache seized from a smuggling group in recent history.

The DRI said the Dongri operation employed 18 Sudanese women. They were arrested while trying to evade scanners at the Chhatrapati Shivaji International Airport. The women carried gold worth Rs10 crore each―as gold dust and paste on skin, and gold capsules in body cavities. They did not know each other. Their mission: obtain Customs clearance and contact a handler, who would extract the gold, melt it and hand it over to a middleman―Yunus Shaikh in Dongri. Yunus, in turn, would deliver it to a jeweller at Kalbadevi.

Of late, India has become a hub for Sudanese syndicates running a booming trans-Saharan gold racket. Sudanese nationals enter India through the porous Indo-Nepal border or fly in from the UAE. In 2023, more than a dozen Sudanese gold smugglers were caught in Patna, Pune, Mumbai, Kolkata, Delhi and Kochi.

Sudan is Africa’s third largest, and the world’s tenth largest, producer of gold. With the Russia-Ukraine war having caused a spike in global gold prices, Sudanese mines are being plundered. The army and rebel forces are fighting each other for control of the mines; hundreds of tonnes of gold are being smuggled out of the country every year. As one of the world’s biggest gold smuggling markets, India has become a hub of this illicit trans-Saharan gold trade. Long-dormant smuggling networks in the country are being activated and new ones created.

**

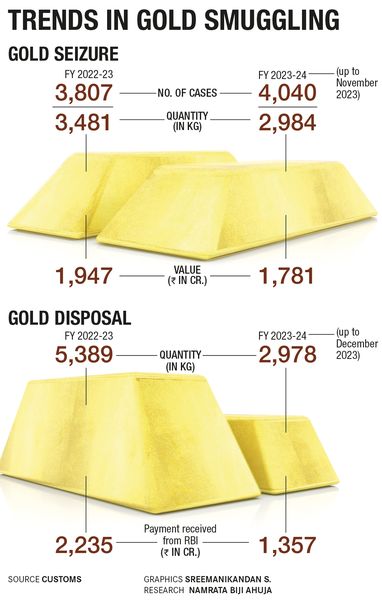

In 2022-23, gold smuggling in India touched a four-year high. Almost 4,000kg of smuggled gold were seized in the first 11 months of the fiscal year. The Union finance ministry told Parliament that the figure was nearly equal to the combined seizures of the previous two years, and 10 per cent higher than the pre-Covid year of 2019-20.

The DRI―one of the leanest Central agencies, with 800 personnel―has since doubled its efforts to bust domestic and international smuggling syndicates. Under its radar are airports and seaports in Gujarat, Mumbai, Kochi, Chennai and Kolkata, and borders between India and Nepal, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh.

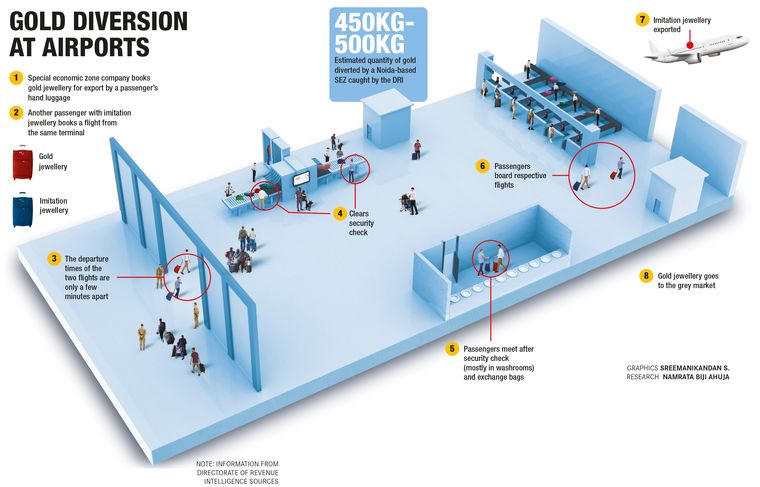

Even as old and new smuggling routes come alive, traditional smuggling methods are being combined with commercial fraud, whereby unscrupulous manufacturers misuse government schemes that allow import of gold bullion without payment of Customs duties. These manufacturers divert gold to the grey market, while fulfilling their obligations under government schemes by exporting copper and other non-precious material.

“The increase in the price of gold in the international market and the substantial change in rupee-dollar parity have increased the landing cost of gold,” said B.V. Kumar, former director general of the DRI. “Smuggling provides an easy opportunity to make quick profits.”

The Dongri bust in 2019 led DRI investigators to the Gulf of Kutch and the Mundra port in Gujarat. Nisar Aliyar, the alleged kingpin of the syndicate, had been smuggling gold from the UAE into these places. To avoid detection, the gold is painted black and concealed in brass scrap. Over two years, Nisar and co. allegedly smuggled in 4,522kg of gold in 55 consignments of brass scrap. The gold was later shipped to several metros.

“Gold has always been a strong substitute for hard cash in India, and considered a safe investment in times of financial uncertainty,” says A. Sakthivel, president of the Federation of Indian Export Organisations (FIEO). “India is one of the top gold importers, but since it hiked import duty on the metal to 15 per cent, the country has recorded a steep fall in imports.” It has since incentivised illicit trade.

The Dongri chase resulted in the arrest of smuggler Shoeb Zarodarwala and his son Abdul. Shoeb told investigators that he was running a tour and travel business when he met Nisar, who introduced himself as a trader of aluminium and brass scrap in Dubai. Nisar offered Shoeb a cut if he helped him move gold in India.

Shoeb personally delivered the first gold consignment of 50kg, and made hawala payments to Nisar in Dubai through operators in Mumbai. A popular identification technique in smuggling was used to deliver the money. The carriers show the image of a currency note on WhatsApp, and it is matched with the note in the hands of the hawala operator. The smuggled gold, meanwhile, reaches buyers who melt it in tiny shops in crowded jewellery markets in several cities.

According to the DRI, 90kg gold worth Rs29.57 crore was siphoned off from the Dongri consignment even before the DRI could lay its hands on it. The agency invoked the stringent provisions of the 1974 Conservation of Foreign Exchange and Prevention of Smuggling Activities Act (COFEPOSA) against the accused. But Nasir still got a reprieve after 18 months, the maximum detention period under the law.

“Correct enforcement of the law is a problem for agencies, which mostly conduct investigations based on information that may or may not be true. It is a situation of wheels within wheels,” said Sujay Kantawala, lawyer at the Bombay High Court. Kantawala has handled several cases of smuggling, money laundering and tax evasion.

In 2022, the government raised the monetary threshold for prosecution and arrests in commercial fraud and smuggling cases from Rs1 crore to Rs2 crore. The threshold for duty evasion and outright smuggling was raised from Rs20 lakh to Rs50 lakh. It means if the value of the smuggled gold is less than Rs2 crore, the smuggler can get bail on the spot.

As profits overtake risks, smuggling goes up. When the RBI decided to withdraw Rs2,000 currency notes from circulation, there was a rush to offload the notes. “What better incentive than to buy gold?” asked Kantawala.

Every day, tonnes of gold smuggled by the transnational network with roots in Sudan make their way into India’s huge grey market. The network is so vast that both private and public companies have come under the DRI scanner. The agency recently found that several well-known private jewellers and the government-owned Metals and Minerals Trading Corporation (MMTC) were part of transactions that flouted provisions of the Special Economic Zone Act, 2005, and misused tax-incentive schemes to manufacture gold jewellery. In 2021, the Enforcement Directorate found that a jewellery firm had laundered money through its transactions with MMTC. The jewellery’s assets worth hundreds of crores of rupees were seized.

India’s appetite for gold is driving commercial frauds as well. In one instance, the air cargo (export) wing at the Indira Gandhi International Airport in Delhi received intelligence that a company based in a special economic zone in Noida had “mis-declared” one of its consignments. The company, which was trading with a jewellery firm, had declared a gold consignment weighing 26.9kg, valued at Rs5.62 crore. But when DRI personnel broke the seal on the package, they found a locked metal trunk with 16 cardboard boxes. Fifteen boxes were labelled “traditional sweets”, and the sixteenth one was a big red box whose invoice said “studded jewellery”.

A jewellery appraiser was soon called in and all boxes were opened. They contained more than 500 pieces of polished yellow jewellery made of copper, nickel and silver. The red box had gold earrings with non-precious beads. The whole consignment had just 3.16kg of gold, against the declared 23.49kg.

The accused told the DRI that the gold was imported duty-free into the special economic zone, and it was sold secretly to buyers in jewellery hubs in Karol Bagh and Chandni Chowk in Delhi. Hawala payments were made to Dubai. According to the DRI’s rough estimates, the Noida company diverted at least 450kg gold using the method.

Officials say they continue to bust such rackets across the national capital region. “The biggest impact is on the exchequer, which not only loses Customs revenue, but also the foreign exchange that could have been earned had the items manufactured from imported gold were actually exported. More often than not, such practices lead to generation of black money and [drive] money laundering,” said Sreekumar Menon, former director general of the National Academy of Customs, Indirect Taxes and Narcotics.

Gold is smuggled into India primarily through two means. Commercial smuggling, where various export and import schemes are misused, and “outright smuggling” by individual carriers who evade Customs duty. Evidence says it is commercial smuggling, rather than smuggling by individuals, that costs the government more. With better intelligence, chances of seizing illegal consignments, identifying kingpins, and prosecuting and penalising them are increasing.

But kuruvis remain a conundrum. Kuruvis, or sparrows, is a popular name for human mules who smuggle gold into India in various forms and pass them on to anonymous handlers. Once these kuruvis succeed in evading Customs check at airports and coastal areas, there is little chance of recovering the gold, say investigators. For syndicates and kingpins, kuruvis are also expendable―they are lone agents who know neither their handler nor the larger network behind the operation.

The payout involved in gold smuggling lures individuals to become kuruvis. Also, it is easier to carry gold than sandalwood, narcotics or foreign currency. Gold is biologically inert, and it can even pass through the digestive tract without being absorbed. The variety of ways by which gold can be smuggled lures many people to take the risk.

THE WEEK met Munna, 40, a former sandalwood smuggler from Chennai who has had many successful runs both as a kuruvi and as a handler of kuruvis. Munna said he started smuggling gold because he wanted to fill his undiyal (piggy bank) as fast as possible. He smiles when asked about his undiyal. “It is a very lucrative business,” he said. “The risk is very high, but each successful consignment can fetch a few crore rupees. The profits depend on quantity.”

Munna ran a network of 300 kuruvis and devised a method using iPhones to double his profits. “Each iPhone can carry 225gm of gold inside. So nearly 40 people can carry up to 9kg gold a day. We used to send people in batches; there were around 300 agents doing the work.”

Even though the DRI is on its feet, Munna said corrupt officials at local level aid the smuggling syndicates. In 2019, though, he got unlucky and one of his consignments was intercepted. “Bribe is paid at various levels of one agency. If all the authorities do their job properly, this won’t be possible,” he said. “These days, gold is carried as paste. Once rubbed with toothpaste or vaseline, it does not get detected during baggage screening.”

According to Munna, airports are the preferred landing point for many gold consignments. “The markings on the gold are removed in big factories in NCR and taken to open markets in Chennai, Hyderabad and Kozhikode. The best market for gold these days is Hong Kong, which offers the highest price.”

A frequent flyer, Munna says a smuggler’s favourite flight would be a transit flight like Dubai to Colombo via Chennai. “Since Sri Lankan authorities check direct flights from Chennai, transit flights are better,” he said.

The stretch of sea between the Jaffna peninsula in northern Sri Lanka and Mandapam in Tamil Nadu’s Ramanathapuram district offers several options to fishermen-turned-kuruvis. The sandy islets off the Mandapam coast, for instance, can serve as landing points. “By evening, the landing points become active and everyone knows that boats will be coming in at certain points,” said Tamilarasan, a fisherman-kuruvi who claimed to have smuggled 35kg of gold before he was caught by the DRI.

Tamilarasan said it was common for fishermen in the region to moonlight as kuruvis. The proceeds from the smuggling boost the local economy in many ways. The Sri Lankan boats confiscated and abandoned by Customs, for instance, come in handy for fishermen near Mandapam. “Often, local fishermen remove the Sri Lankan markings, paint them and refurbish them, and use them as regular boats,” said Tamilarasan.

But there are those who have burnt their fingers. THE WEEK met a carrier who was caught in 2020 while trying to smuggle gold on a two-wheeler from Rameswaram to Chennai. He said he wanted to make a quick buck because his mother had fallen ill. “I simply had to pick the packet from the landing point at Mandapam and deliver it to an agent in Chennai. I am probably the only gold smuggler in the entire region who got caught the very first time. I lost more than I earned,” he said.

Gold smuggling has been causing political storms as well. In 2020, the Customs in Thiruvananthapuram seized 30kg of 24-carat gold from a diplomatic bag meant to be delivered to the UAE consulate. This was the first case that pointed to the existence of a transnational network involving diplomats, bureaucrats and smugglers. The Enforcement Directorate said it cracked encrypted voice recordings of conversations between hawala operators and gold smugglers. In February 2023, the Financial Action Task Force, a global anti-money laundering agency, said smugglers were using alternative banking systems (hawala) to facilitate currency exchange for purchasing gold in the Middle East, illegally transporting it to India through diplomatic bags, selling it on the black market, and turning them into jewellery for retailing.

The growing demand for purity has smugglers focusing on the India-Myanmar border. Intelligence reports say armed ethnic groups that illegally run gold mines in states such as Kachin, Kayin, Mon and Shan in Myanmar are driving the cross-border gold trade. The groups refine gold by crude methods and take it to border towns where it is converted into gold bars.

Also Read

- Congress leader tipped off ED against Karnataka minister in gold smuggling case: H.D. Kumaraswamy

- Ranya Rao gold smuggling case: D.K. Shivakumar’s ‘wedding gift’ claim puts Parameshwara in a spot amid ED probe

- Gold smuggling case: Ranya Rao’s bail plea rejected; DRI makes third arrest

- Gold smuggling case: Kannada actress Ranya Rao’s bail plea rejected; DRI seeks CBI support for expanding probe abroad

- Kannada actor Ranya Rao says man in 'Arab clothes and African-American accent' gave her the gold at Dubai airport

- Why did Karnataka govt drop CID probe in Ranya Rao gold smuggling case?

Smugglers have been exploiting the ‘free movement regime’ on the India-Myanmar border that came into effect in 2018. Apparently, gold from Myanmar enters India mainly through border towns such as Zokhawthar in Mizoram and Moreh in Manipur. It is then taken by carriers on customised cars, vans, buses and trucks to Aizawl, Silchar, Guwahati, Kolkata, Delhi and Chandigarh. Apparently, demand has so grown that crude gold from Thailand and China is now entering India via Myanmar. On February 8, the Union government announced the scrapping of the free movement regime.

M. Ajay, advocate at the Kerala High Court, said the first step in curbing smuggling was to make it less lucrative. Also, he said, law enforcement agencies needed to keep pace with the changing nature of offences. Often, they take the easier option of detaining offenders under COFEPOSA, which Ajay said was not a punishment for offences committed but a law to prevent the commission of more crimes.

“I have not seen many cases where end-users who put [smuggled gold] to commercial use are investigated,” he said. “It is only small fish that get trapped in long years of litigation.”

Sample this

Mumbai saw the most seizures in January 2024; three sample case studies

BOOTY UP THE BOTTOM

Two residents of Thane, Maharashtra, travelled from Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, to Mumbai by Vistara Airlines flight no UK236 on January 18. They were intercepted based on specific intel and eight pieces of “24-carat gold dust in wax” were found concealed up the rectum. The haul weighed a combined 2.42kg and was valued at Rs1.34 crore.

SEAT EXCHANGE

A resident of Tiruchirappalli, Tamil Nadu, flew from Thiruvananthapuram to Mumbai on IndiGo flight 6E5108 on January 17. The flight had come from Sharjah earlier the same day. The authorities got a tip that during the international leg, gold was concealed under seat 10C and that during the domestic leg the passenger in 12C would recover it and try to exit from Terminal 1. Upon arrival in Mumbai, Customs officers nabbed the passenger and recovered “two pieces of 24-carat melted gold bars” weighing 1.448kg, valued at more than Rs80 lakh.

WATCH YOUR STEP

A resident of Dwarka, Gujarat, flew from Dubai to Mumbai on Emirates flight EK500 on January 23-24. Four pieces of “24-carat crude gold jewellery” were found concealed in the shoes worn by the passenger. They weighed 1.419kg.