One morning in March, in a packed classroom in a free coaching centre in the village of Kuchai in Jharkhand’s Saraikela district, Sombari Munda raised her hand when asked whether there were any young people who were going to vote for the first time. “In the last few years, I have taken a good look at what life is like in my village, and I have already made a decision about my vote,” said the 18-year-old. “We got electricity a few years ago, and now we also have water. But the quality of education is still very bad. When I enter the polling booth, I am going to hit NOTA (none of the above).” The room erupted in a ripple of laughter. “Why should I give my vote to someone who has done nothing for us?”

As I listened to this young woman, an admirer of the fiction of Premchand and the poetry of Hazari Prasad Dwivedi, elaborate on her carefully considered thumbs down to the entire political class, I was reminded of why youth―spiky and soulful, hopeful and discontented, perceptive and profound―is thought to be the greatest of life’s seasons, even (perhaps, especially) by those who have left its station. I thought of Premchand and Ambedkar and Gandhi and the scores of anonymous democratisers of the 75 years of the Indian republic, and how, for different reasons, they would all have enjoyed such a moment. And I was glad for this chance to go back to school, literally and metaphorically, for a month, to get a sense of the aspirations of the youth of India, and to what extent they had faith in politics and the vote as a way of addressing them.

India has long been a country where the young are ubiquitous, yet tightly marshalled by the structures of family and society and religion. Youth in India is paradoxically short and long at the same time. Many turn breadwinners at an early age, or are exposed to challenges and tribulations for which they are unprepared. At the same time, so many young people live with and are beholden to their parents long into adulthood, and have an instinctive respect for age and authority that sometimes makes them discount their own rights and power. Looking around, it is clear that the youth have huge market power: as consumers of smartphones and sneakers, fashion and fast food, cricket and cinema, laptops and coaching classes. The rise of social media means that Generation Z also has huge visibility and voice in the public sphere.

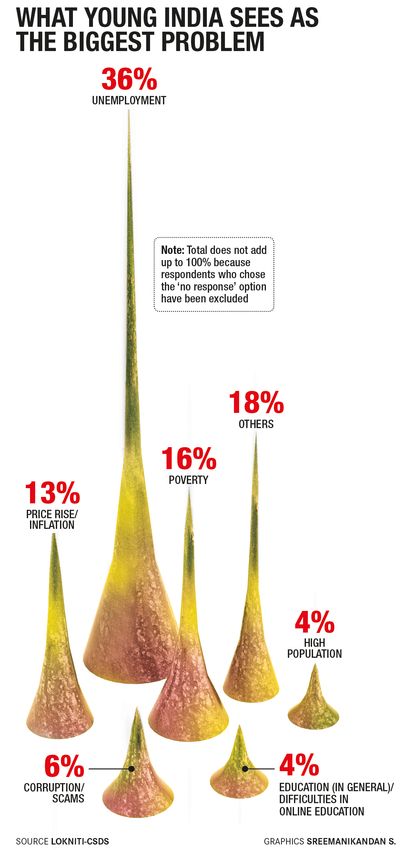

But relative to their size, the political power of India’s youth is much more diffuse and hard to gauge: both in terms of their issues (education, employment) not being given enough weight in the policy agenda, and their political voice and participation being underdeveloped and often actively discouraged. When we think of the instances when youth power expressed itself most visibly as a political force in the last five years―in the nationwide protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act and the farmers’ protests in Delhi―it is astonishing how swift the government and certain sections of society are to characterise the young as misguided and immature. Nor is there the same sense of role models in politics, of a roadmap from aspiration to achievement, as there is in cricket or social work, entrepreneurship or music.

“In a country with a demographic pattern like India’s, logically the political space should be dominated by the youth and their concerns. But it is not,” said Ashwani Kumar, dean of the School of Development Studies at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), in Mumbai. “Also, millions of youth, especially those hailing from the poorer eastern states of India, are also politically disenfranchised because they are migrant workers, who live in a different place from where they are registered as voters.” Although they are courted by all political parties, the youth are greatly under-represented in Parliament. In the 17th Lok Sabha, more than 58 per cent of MPs were between the ages 46 and 70, and only 12 per cent were below the age of 40.

This precedent will continue in this summer’s election as well. The voter seen passing through the polling booth will typically be someone aged between 18 and 30, voting for a candidate between 45 and 65. A strange situation for a country that has more young people today than any other country in the world. Those under 25 make up nearly half of India’s population; for those under 35, the figure is 66 per cent. If the demographers are right, India will never have so many youth as in the years between 2020 and 2040―the final upsurge of a trend going all the way back to the post-independence years.

What are the main themes and forces shaping the politics of young people today? The youth may be part of many vote banks, but because of their even dispersal across regions and classes and the diversity of their life situations and allegiances, they are rarely an organised political force. What links the backpack-carrying student of IIM Ahmedabad with the youth from rural Odisha arriving on a construction site in Kerala or a farm in Haryana? Are there more walls than windows between a student preparing for the civil services examination in a public library in Kochi and a dosawala her own age outside the gate from whom she buys a meal?

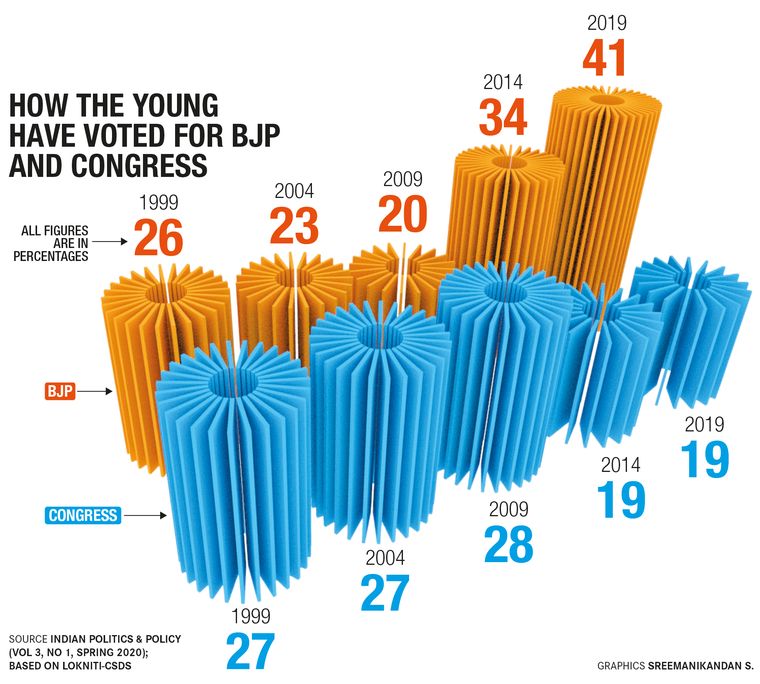

Today’s young voters between 18 and 29, I found, are distinct not only because they are the first generation in India to live in partnership with their smartphones and to invest so much time and emotional energy in their virtual selves. They are also the first generation of youth in independent India to have been politically socialised in the age of full-force hindutva, even as the long-term transformation of Indian society post-liberalisation continues, offering exciting new opportunities to young people and increasing inequality and social restiveness.

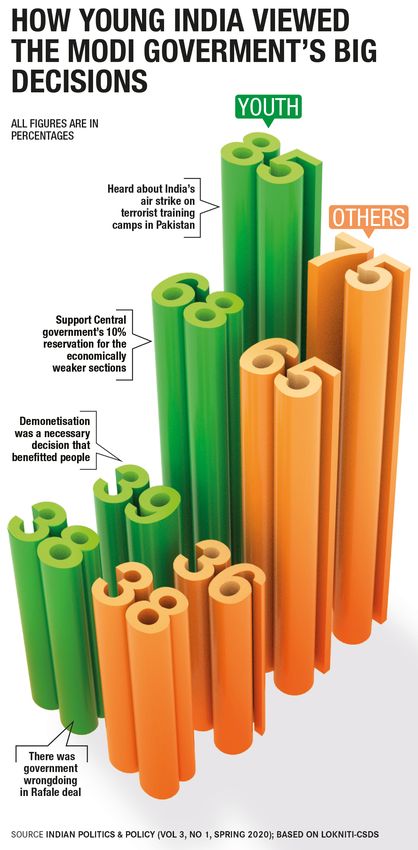

As Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the BJP seek a third consecutive term, the state they have fashioned has a distinctly different relationship to the youth than when Modi first assumed office in 2014. The rewriting of school and college textbooks, the diffusion of a new pantheon of exemplars and role models from the annals of the Indian past, the creation of a new right-wing ecosystem that glorifies nationalism, hard power and charismatic authority (never more so than the charisma of Modi himself), the crackdown on dissent in university spaces and demonisation of youth activists such as Umar Khalid or Natasha Narwal―all these trends are part of an attempt to dramatically reshape the relationship of young Indians to history, politics and society, even to democracy and political authority itself. The youth are encouraged to critique the past―the Mughals, colonialism, Nehru, the Gandhi family―and to celebrate the present. The country, the ruling party and the prime minister are all projected as one indivisible whole, to which recently has been added the figure of Lord Ram.

In effect, not only do young voters aged between 18 and 29 comprise a new generation, they are obliged to make sense of a different idea of India and to navigate a more hegemonic political discourse than any previous generation since Indira Gandhi’s Emergency. To add to the young person’s tumult of what life itself means and what the future holds, the youth today have to decode a welter of mixed messages about what sort of country they live in. Alongside their worries about education and livelihood, they are the site and subject of a tremendous struggle between the progressive and modernist ideals of the Indian Constitution and the Hindu-centric and hyper-nationalistic counter-revolution orchestrated by hindutva.

“There is among the youth today the persistent fear of being policed on personal choices like religion, identity, marriage, and, sadly enough, even food preferences,” said Anushka Chatterjee, a 24-year-old writer from Kolkata. Some pointed out the contradictions of a regime that seeks to portray all dissent as anti-national or politically motivated, yet insists that India is the “mother of democracy”. How could both things be true at the same time?

“I think that, just as it has gradually succeeded in changing the meaning of the colour saffron, the BJP aims to change the meaning of the word ‘democracy’ itself,” said Madhuri Adwani, 29, a podcast producer whose work involves documenting “everyday acts of rebellion” by women. “If this is what they have done to textbooks in 10 years, imagine what our textbooks will say another 10 years down the line. A young person in that time might never be able to trace what really happened in our freedom movement, or how our Constitution came into being.”

Are the youth of India willing to accept these revised terms of engagement with political authority and this remaking of the meanings of key words and concepts, including democracy itself? What is their analysis of the economic and cultural transformation of India over the last decade? Are their lives as political actors contiguous with other aspects of their existence, or separate from them? Is politics a realm of hope and optimism for this generation, who will form the core of the electorate in the final quarter of the first century of Indian democracy, or of disenchantment and confusion? Are alert and critical young citizens like Munda and Adwani widely found among the young? I wanted some sense of the conversations and experiences the youth had traversed to arrive at the answer to the question: how will I vote?

Pradeep Goswami lives a life of iron discipline. At 23, this resident of a village near Varanasi is already a father of two and possesses a breadth of experience. After a two-year stint as an Uber driver in Mumbai, Goswami returned to his village in 2020, just before the pandemic, and invested his savings of Rs3 lakh in a small business manufacturing agarbattis. When the business did not work out, he reluctantly sold off his equipment and returned to Mumbai to resume driving on the Uber platform. In Mumbai, he lives with three other migrant workers, including his older brother, in a tiny room “no bigger than my car”, paying a quarter of the rent of Rs8,000. He makes around Rs20,000 a month, but tries to spend no more than Rs5,000, transferring the rest to his mother’s bank account. A Brahmin, he takes pride in his lineage―“I come from the same line as Goswami Tulsidas”―and although he is a perceptive critic of some traditions of Uttar Pradesh―“the biggest problem is that as soon as we come of age, our parents get us married”―he does not see rebellion as a practical option, as the joint family is a source of economic support and emotional security.

There are many interesting dimensions to Goswami’s politics, which are highly aware in some respects and detached in others. He said he paid no attention to the endless flow of news; nor did he consume information about politics on social media. “I concern myself mainly with my work,” he said. His views on politics stem from his personal experience and from conversations with others; he believes this is a more genuine way of making sense of the country than listening to politicians, “whose only aim is to make the public fight with one another”. Traditionally, his family has supported the Samajwadi Party, taking their cue from Goswami’s father; Goswami’s favourite politician is Akhilesh Yadav. But a dissenting opinion in his household has recently emerged in the form of his oldest brother. “He is a kattar (staunch) BJP supporter and often argues with my father, trying to prove that the BJP is right on all kinds of issues.”

When India goes to the polls this summer, Goswami, being resident in a place far from his village, will be one of several million migrants who will not be voting. That does not make him any less interesting as a political actor. Fascinatingly, he says that if he could vote, he would vote for the BJP, which he has just criticised for its obsessive focus on the “Hindu-Muslim issue”. Why? Since it is very clear to him that the BJP will win. “I wouldn’t want to waste my vote by voting for some other party.” Both in his family life and his politics, then, Goswami reveals a certain respect and regard for entrenched forms of power and authority. His dissent and critique, although highly cogent, exist in a private realm, while his social and political choices are more in conformity with the broader trends in society, or the “hawa” in electoral politics.

The thoughts of Dilip Yadav (name changed), 25, another taxi-driver in Mumbai from Modi’s constituency of Varanasi, almost perfectly exemplify the worldview of another kind of young Indian voter. Despite their personal circumstances not having improved a great deal, these voters feel that the larger stock of economic capital in the country has definitely seen an uptick in the last decade, as also the place of India in the eyes of the world.

“I am happy with the BJP because they are working much more efficiently than the previous governments did,” said Yadav. “Our Nitin Gadkari is doing a good job. He is building roads and highways so fast, and without wasting money. Look at Mumbai. How long did the Congress government take to get a single phase of the Metro line built from Andheri to Ghatkopar? Ten or twelve years. But in such a short span of time, the BJP government has opened a number of new lines. In Uttar Pradesh, law and order was a huge problem. But crime has gone down significantly under Yogi Adityanath’s government. In the past, there was not much respect for India in the world. Now the entire world is talking about us.”

Yadav said he liked everything about the BJP except the party’s focus on creating a divide between Hindus and Muslims. I asked Yadav about what he thought of young Mumbaikars. He said he felt alienated from them as they frittered away their parents’ money on indulgences such as alcohol. He said their privileges made them blind to the lives of people like him.

More than religion or caste, I could see a kind of political solidarity emerging around the question of “shram” or diligent work, something that might have pleased Gandhi and further disoriented the communists. During my travels in Ayodhya, Varanasi and Prayagraj in January, I found that middle- or lower-middle-class voters in north India had a very strong connect to Modi. They saw him as hard-working and anti-elitist, in tune with traditional Indian values and the struggles of the poor, and with a grand vision for the nation that was being realised on the ground by the committed and disciplined cadre of his party. To use a metaphor, the prime minister was like a wise and stern patriarch of a large and unruly joint family. It was more practical to ignore some of the less palatable aspects of his thinking than to start a dispute with him that one would almost surely lose.

Not that patriarchy and centralised authority are not being broken down in some other realms of Indian life. “In my childhood, I remember that voting was a family affair,” recalled Vilasini, 28, a documentary filmmaker in Chennai. “The head of the family would decide who the most worthy candidate was, and the others would fall in line. But now families have become a very interesting space in Indian life. There is a possibility for new kinds of conversation inside the family. Older people are like, ‘We actually want to listen to what you want to say.’”

What is the message that Vilasini is trying to communicate with her own vote? “Much more than in 2014 and 2019, my vote this time is a rejection of the Central government and its ideology,” she said. “Sure, it may be a popular government and I want to understand the reasoning of the millions who support it. But there are also so many more people in India today who are being challenged by the state because of who they are, so how can we call this a people’s government? I don’t want a government that is divisive and practises religion-based politics. One source of hope for me is that there are Indian states that think differently from the rest of the country, including my own. The strong feeling about many young people I know is that the BJP should not be allowed to make inroads into Tamil Nadu.”

Even so, she could not deny a feeling of disillusionment, the sense of an impasse. “We may be clear that we do not want this sort of country. But there is no clear imagination of what we actually want in its place,” she said. “There is a vacuum.”

Many young people voiced a similar sense of the lack of a constructive agenda in the opposition space. “The intention behind Rahul Gandhi’s Bharat Jodo Yatra was good,” said Adwani. “But in the end it was mainly symbolic. You walked through one city on a particular day and left. But how do you make sure that the thousands who came out to join your rally remain with you? The yatra had a lot of promise, but it could not work out how to generate long-term attention and commitment from the youth. I don’t think the Congress has an action plan. The leadership within the party and the wider opposition is still very weak. For example, I feel that the Aam Aadmi Party is doing some good work in Delhi, but sometimes it also lapses into the language of majoritarianism. Actually, the people in the political space that I identify with are not politicians, but political activists whom the government tries to put into jail, like the ones who stood up against the CAA.”

Tauhid Alam Khan from Kolkata said the only noticeable change in the nature and focus of governance was that the current dispensation had become even more confident in pitching laws and courses of action “which were gimmicky, polarising and with questionable constitutionality”. “We have seen various forms of instant justice being implemented, be it deaths of criminals in police custody, or the much talked-about demolition drive via bulldozers which seem to target a particular community over the others,” said the 27-year-old, who has a postgraduate degree in English from Aligarh Muslim University. “Experiments with the uniform civil code in Uttarakhand project it as an impending constitutional duty without setting up a proper framework or creating a discussable draft. This government comes up with only what could attract the most eyeballs and polarise an already polarised society, along with winning the confidence of their consolidated vote bank who make them seem electorally invincible.”

Like many other young people, Khan felt that the government tried to distract the electorate through strategic interventions in the news cycle. “The sudden move of implementing the CAA, right on the eve of the polls, feels like nothing but a shroud over the findings of the Supreme Court on the issue of electoral bonds and the subsequent revelations about the donors, which have elements of bribery, scams and extortion,” he said.

“In the wake of the Ram Temple inauguration, people have become so public and so aggressive about their devotion,” said Shachi Ankolekar, 24, a designer and tattoo artist in Mumbai. “Also, Hinduism has become more north Indianised. Friends of mine who are from minority communities feel threatened today. There is a shortage of safe spaces in which to have these conversations now. But you should never create that feeling among people if you are trying to govern a country.”

Ankolekar also brought up the matter of integration of different sectors in the country into one large complex, each promoting the agenda of the others. “The government, the big business, the new temple, and the film space... these have become like four tiers of one entity,” she said. “Look at the recent high-profile wedding. The addition of the film space made something that was very pure for me become...I was like, what the hell?”

There were other kinds of political vacuum I discerned during my travels. Often, politics itself is a vacuum in the imagination of young people: a mysterious realm of duplicity where nothing is as it seems. Although the youth are being encouraged to vote, many have no sense of participation in the processes of politics other than this one quantifiable, ritualistic gesture. For those from poor families with low social capital, often the material struggles of their lives are so onerous, and their sense of deference to authority so deep-rooted, that their lives are set up to ruffle as few feathers as possible. The gulf between their existence and the lives of those chosen to represent them is so vast that the rulers and the ruled seem to inhabit two different orders of reality. The “system” is out there―vast, inscrutable, cynical and opaque, although clientelist and rich in spectacle. Citizenship and equality are all very good as ideals. But there are many battles to be fought that are much more immediate and demanding.

In the courtyard of a boy’s hostel in Jharkhand’s Seraikela district, I asked the students―most of them aged between 18 and 22―about their politics, their idea of citizenship and their relationship to democracy. I might as well have been talking to a wall. Even the mango tree rustling above our heads seemed to have more to say.

“You see, sir, our main focus in life is how to study and somehow get a government job so that we bring financial security to our families,” said Shiv Narayan Munda, 21, after this long silence. “Our parents have instructed us not to get involved with politics at all.” Munda’s dream is the dream of millions like himself. In a recent Lokniti-CSDS survey of close to 10,000 youth, 61 per cent said they were seeking a government job. Munda was upset when he missed the deadline to apply for the Army’s Agnipath scheme. Those youth seeking so desperately to work for the state have little to gain from criticising the government. Those in the private sector are increasingly able to jettison the realm of politics entirely, their wants and needs all catered to by the market and their moral universe centred in the me-first ideology of neoliberalism.

Lower down the ladder, they are often too harried to make time for political participation. “My work and family take up all my time. Sometimes I am at the hotel 24 hours a day,” said Udhay Biswas, 27, the diligent young manager of Aster Heritage Hotel on Park Street in Kolkata, and a new father. “I really do not have any time for politics, nor does it touch my life in any way. I will vote according to what my parents say.”

And there are many whose lack of interest in politics is itself a political gesture. Since politics is orchestrated and managed from a faraway place, it is futile to waste time on it. Although the BJP has successfully transformed the character of the Indian state and even the range, reach and efficacy of social welfare schemes, it has done so while further entrenching the popular perception of politics as rooted in an immense greed for power and money, as a thundering juggernaut unconstrained by ethics or norms. Participation in the political process and support for the ruling party is not inconsistent with a feeling of alienation from politics. There is a sense of moral disquiet to which the youth are perhaps more alive than their elders. “Every ruling party primarily looks after its own interests. They are all on the take,” said Yadav.

Even with a high youth voter turnout of over 65 per cent, could one celebrate such a view of democracy? If the youth have their own dreams for democracy that are not linked to the exercise of their political franchise, what are they?

Many young people I met derived great strength from their relationship with God. Some had very striking thoughts about the divine, which could not have come from any book. “Bhagwan bhi ek manushya hai (God is also human),” said Sanjeeth Kumar Kamat, 24, a farmer’s son from Bihar’s Madhubani district, who recently moved to Kolkata to drive a Uber cab after some years in Bengaluru. We had been discussing the idea of labour. For Kamat, no one in the world is exempt from the need to work, not even God. “It is only when He works for us that we bestow Him with food and flowers.” The thought would have delighted both Marx and Kabir.

Perhaps because of his perception that he was a link in a chain of labour going all the way up to the Maker, Kamat was the most contented person I met on my travels. I think what many young people are missing, despite the presence of so many authority figures in their lives, is a guide in this world, someone who could provide them with a stimulating environment and a sense of purpose, who could help direct and focus their idealism and talent. “We have a great shortage of role models in our lives,” said Rajkumari Pradhan, a 22-year-old from Jharkhand working with Ugam, an NGO specialising in education and women’s empowerment. “The most difficult battle of my life was to convince my parents that I needed to study further after my matriculation.”

Some young people, while working their way up in life, have themselves become guides for others. The youngest of five siblings, Dharmender Oraon, popularly known as David, an adivasi, grew up in stark poverty in Saharbera village in Jharkhand. His father, a labourer, earned Rs60 a day. David remembers asking his mother for a refill for his pen in his childhood; there was no money for one. “Even so, my parents never took us out of school and put us to work. They wanted me to study,” said the 27-year-old. “I was in the sixth standard when I first heard the sound of ABCD. The language of my tribe is Kurukh; my schooling was in Hindi. After that, it was a great struggle to learn English. Language is a huge struggle for us, that is why you see many young people in Jharkhand trying for jobs in railways and defence, where the knowledge of English is not so important.”

David failed to get a job in the railways. He applied for a BEd programme in Jamshedpur and, with the help of a scholarship from the Jharkhand government, is now close to getting his degree. But he is already a teacher and guide to every youth in Saharbera. With the help of Sanjay Kachhap, a young bureaucrat known as the “library man of Jharkhand”, he set up a library in a room in his village school. There, every evening, all the children of the village assemble to study together, a cluster of youth “from KG to PG”. The older ones help the younger ones, and each other, too. “Someone’s maths is good, someone’s general knowledge is better than the others.” They also practise conversational English.

In five years of him running the library, said David, as many as nine youth from Saharbera, including one woman, cleared government exams. “It was very inspirational for the girls of the village. Previously, our elders used to ask us, ‘What will you gain by studying further?’ Not any more.”

David’s role models are two figures from historically marginalised communities: B.R. Ambedkar, because of his commitment to education as the road to selfhood and power, and the late adivasi politician Baba Kartik Oraon (1924-1981) of the Indian National Congress.

Almost eerily composed and clear-headed, David has views on a vast range of subjects, from the farmers’ protests to education. “We are a country of many faiths, many thought-systems,” he said, when I asked him about what he made of India in the age of hindutva. “If the country is dominated only by the agenda of hindutva, then many other good things will be left out. For instance, the adivasi idea of jal, jangal, zameen (water, the forest, and the land) is so important if we are to reform our relationship to nature.”

“We are in an age of social media,” he observed. “Grand claims are made about the past and the present in short videos and reels. I appreciate the government’s work on projects like Skill India, which are trying to give vocational training to the youth. But when I hear other young people saying we have entered a golden age, I ask them, ‘Can you tell me why we rank so low on the Global Hunger Index?’”

Several other youth I met were, like David, working on projects to deepen a sense of community and fraternity among people. “I want to work for others, to understand their feelings. Whatever we have to work with between ourselves, let us make use of that,” said Poonam from Chandigarh, a student at the vocational school of the Aurobindo Ashram in Delhi.

In her storytelling collaborations with women from rural communities in her work in Delhi, Adwani was able to trace a similar journey of discovery. “When I was growing up in Gujarat, I was very passive in my politics,” she said. “I was very isolated. Politics was very closely linked to business. You supported the party that helped you do business. Women were not supposed to have a political opinion different from the men of the family. But after coming to live in Delhi, I gained a sense that so many things you do in your everyday life can also be political. There are so many solidarities I could be part of and help to create. Today, I want to expand the ‘I’ so that it is in conversation with different communities and generations of women,” she said. “When that happens, you find that the ‘I’ also comes back to itself in different ways.”

At the vocational training school of the Aurobindo Ashram, I also met Subham Mourya, 21, from the village of Sewaith near Prayagraj and now a student of photography and videography. “Here in the city, caste has a very small role in life,” he said. “But in the village in Uttar Pradesh, caste consciousness―who can sit with whom, who can eat with whom―overpowers everything else.” While he was still in his teens, Subham set up an NGO, Hamari Aawaz Pustakalaya (The Library for Our Voice), in Sewaith. “The idea was that those of us who were older could give tuitions to the children of the village, irrespective of caste and religion. Unless you lose your sense of caste consciousness early in life, you end up carrying it all through life,” said Mourya. “What I have observed about caste and religious groups is that they believe all kinds of bad things about each other. In truth, actual human beings are not like that. But we tend to lock each other up in our idea of the other.”

Mourya was making an important point about freedom and democracy. In our social relationships, we have the capacity to make one another free in a way that the state could not, however much it came up with laws to interdict the prejudices of caste and creed. In that sense, as much as it was fashioned to be a system of political representation and legitimacy, democracy was also intended to be a kind of moral challenge to the people of India. Could they chisel away in their daily lives at the hierarchies and age-old social disablements of their world? Many youth dream of things that their elders had lost sight of. Progress for them is also about breaking down the walls between themselves and others. It is a yearning that is as much a part of Indian history as the violence and prejudice that were often dominant. They are sceptical or cynical about electoral politics, but not about human relationships. Their politics occupy a realm different from that of their vote.

“If it were possible, I would make everyone belong to the same God,” said the taxi-driver Dilip Yadav, when asked what he could change about Indian society. But he said that people would never agree, and would rather die than allow that to happen.

“Samaj hi raajneeti ko badal sakta hai. Raajneeti samaaj ko badal nahin sakta,” said Kamat. “Only when we change our society, can we change our politics.” And with a gentle smile reminiscent of the Buddha, he drove off into the Kolkata night.