SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY

A nation’s quest for national identity building, stability and social transformation depends on the development of science, technology and innovation (STI). The growth of China and India is dependent on technological transformation and technological leadership. As positive indicators of success, both countries are rising steadily in this field.

China is an upper middle income country and India is a lower middle income country. Being neighbours and starting their independent growth journeys simultaneously, they often prompt comparison between them. To forecast the future growth trajectory and global power trends involving these two countries, the science, technology and innovation (STI) indicators serve as a global framework for measurement, analysis, comparison, technological intelligence and strategic statistical data. The chief components of these indicators include research and development endeavours and innovation systems.

India began its post-independence journey with the goals of modernisation and, having missed the industrial revolution, focused on planned public investments in higher education, science and technology, agriculture, energy and industry. As India faced a volatile strategic environment, S&T in defence and military became a necessity. The Indian space programme, nuclear programmes and Antarctic programme benefited from the support of the Soviet Union and sporadic contributions from the US and other western powers.

India has rolled out four strategic documents for STI since 1947―science policy resolution (1958), technology policy statement (1983), science and technology policy (2003) and science, technology and innovation policy (2013). The fifth one is soon to be launched as the national science, technology, and innovation policy and is under public consultation. These policies have underlined priorities, sectoral focus and strategies for STI development in India.

China had rapid STI development between the 1980s and the 2020s. Its ‘863 Plan’ and ‘strategy for rejuvenating the country through science and education’ were instrumental in allocating funds, research investment, reform implementation and popularising STI. After opening up the economy in 1978, China came out with such STI policies as the national medium-term and long-term programme for science and technology development (2006–20), the strategic emerging industries initiative, the Internet Plus initiative and the Made in China 2025 programme. The socioeconomic gains of these policies are reflected in China’s geopolitical influence and economic rise.

For India and China, the STI policies remained development and security-oriented between the 1950s and the 1990s. Many scholarly analyses refer to Mao and Nehru’s guiding visions as techno-nationalism. In India’s case, it was grounded in a desire to reduce reliance on foreign technology and promote independent development, autonomous from the power politics of the two blocs. Chinese techno-nationalism is rooted in its underlining of the ‘century of humiliation’ at the hands of western powers in the 19th century.

Of late, the two countries’ visions for guiding STI development have presented a sharp contrast. The ‘Make in India’ initiative of 2014 focused on improving investments and infrastructure for domestic and foreign manufacturing capital, targeting 25 economic sectors. In 2018, President Xi Jinping pushed ‘indigenous/independent innovation’ (zìzhuˇ chuàngxīn) policy of the 1990s owing to concerns of national security after a spate of technology-focused sanctions by the US. Since then, Xi has given the ‘two bombs, one satellite’ (liaˇngdàn yīxīng) call to close the technology gap with the west.

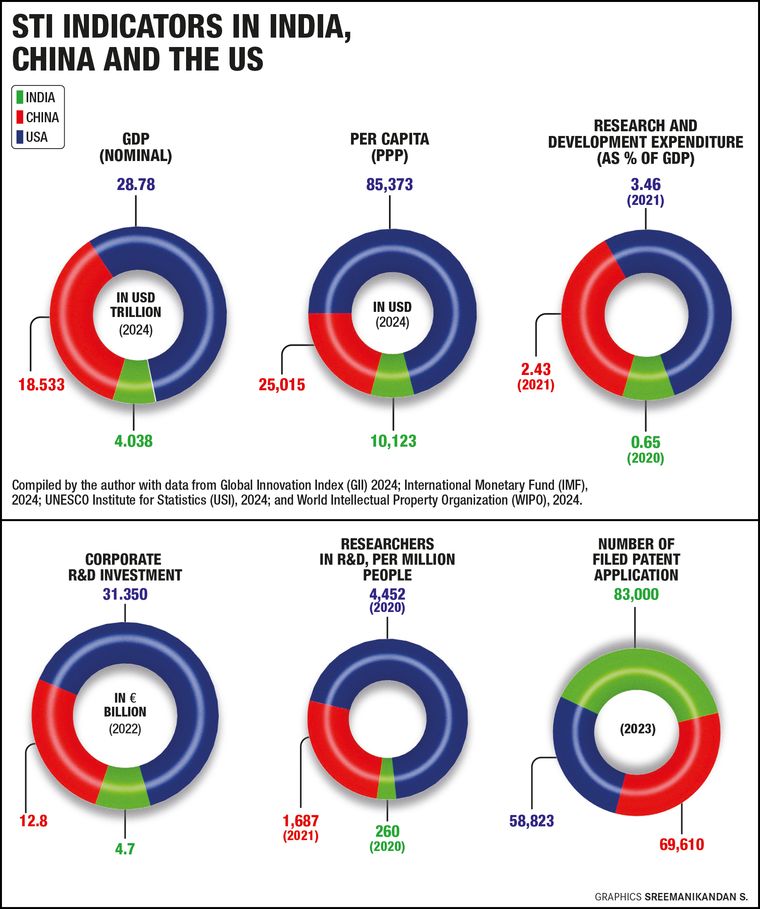

Apart from the philosophies guiding the STI policies, the material stocktaking of STI development depends on certain indicators. These indicators of STI growth can be divided into contextual indicators, such as research and development (R&D) policies, public and private investment, and technology market evolution, and performance-based indicators such as patents, research outputs, university-industry collaborations, R&D talent, and scientific and commercial innovations.

It is essential to contextualise India and China according to global standards. The Global Innovation Index (GII) Report 2023 says the global spending on R&D was $1.7 trillion. Ten countries account for 80 per cent of this spending. There has been a steady increase in R&D investments by private players globally since 2003. The top companies collectively invested $1.4 trillion in 2022. Pharmaceutical and biotech companies dominated the R&D investment in 2020 and 2021. Information and communication technology (ICT) companies were the top investors in 2022.

Further, in the top 100 innovation leaders (companies) in 2022, technology-related companies (47) dominated, followed by health care (24), energy (16), infrastructure and industry (12) and financial services (1) sectors. About half of these 100 innovation leaders are based in the US, followed by China (17), Germany and the Netherlands. Chinese companies accounted for 12.2 per cent of this spending. In contrast, three Indian companies (Tata Motors, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Dr Reddy’s Laboratories) are the top investors of R&D in middle income countries with a cumulative investment of $923.73 million.

China and India have shown a steady rise in GII. However, the difference is telling. In the 2023 GII, India was ranked 40th among 132 economies. Its rank was 66 in 2013 and 81 in 2015. The value of venture capital recipients, service exports, information and communication technology improvements, and startup funding contribute to this increase. India is placed highly in several GII 2023 key indicators, including worldwide corporate R&D investors (13th place), graduates in science and engineering (11th place), venture capital flow (6th place) and exports of ICT services (5th place). By 2025, sales in India’s IT industry will surpass $300 billion.

Government initiatives such as Digital India and IndiaAI aim at technological transformation to the next level with modern technologies like cloud computing, artificial intelligence and the internet of things. In 2023, India stood out as a significant contributor to the growth in patent filings, with a 44.6 per cent increase over the previous year in PCT (Patent Cooperation Treaty) applications. This follows a 25.9 per cent growth in 2022, indicating a strengthening and expanding innovation ecosystem in India.

China was ranked 12th in the 2023 GII. It stood 35th in 2013. It is at the forefront of global innovation, leading in the number of scientific and technological clusters. Shenzhen-Hongkong-Guangzhou, China’s most productive cluster, has submitted 1,13,482 patent applications and produced 1,53,180 scholarly articles in the past five years. While focusing on innovation, China earmarked 20 large mega projects in areas such as nanotechnology, high-end generic microchips, aircraft, biotechnology and new drugs in 2006. The Australian Strategic Policy Institute study (2023) says China is a global leader in 37 out of 44 critical technologies. These include 5G internet, electric batteries and hypersonic missiles.

Also Read

- Can democratic India compete with authoritarian China when it comes to rapid economic development?

- Bilateral diplomacy is a never-ending tightrope walk for India and China

- China is ahead in military might, but India is catching up fast

- India must take a leaf out of China's cultural diplomacy and strengthen research on Beijing

- Both India and China use soft power to influence global opinion

- There has never been a better time to pursue a trade deal with China

Since 2011, China has filed the largest number of filed patent applications in the world. In 2023, it filed 25 per cent more patents than the US. In corporate patent filings, Huawei Technologies from China maintained its position at the top with 6,494 published PCT applications. South Korea’s Samsung Electronics and the US-based Qualcomm followed with 3,924 and 3,410 applications, respectively. Another Chinese company, BOE Technology, came fifth with 1,988 patent applications. China’s legal framework for intellectual property protection, however, is still less developed than most industrialised nations.

In conclusion, the STI development in India and China is asymmetrical. India is expected to register a higher growth rate than China in the years to come, with the S&P Global Market Intelligence projecting 5 per cent growth for China and 6.7 per cent for India in 2024. Further, India is expected to take significant lead in sectors such as health care and insurance, renewable energy and information technology.

The main challenge for both China and India is investment in sustainable STI. Both countries aim at reducing STI interdependency risks and enhancing industrial performance through investments. To achieve this goal, international STI alliances among compatible economies need to be strengthened. Further challenges include disruption of integrated global value chains as witnessed during the pandemic, and the ‘decoupling’ of STI activities because of economic competitiveness and national security concerns.

The author teaches at the University of Delhi, and is an honorary fellow of the Institute of Chinese Studies and associate editor of China Report.