TRADE & COMMERCE

The trajectory of India’s economic relationship with China has largely defied the desired course set by New Delhi in the past two decades. Heightened distrust after the Galwan clashes in 2020 has further widened the gap. Modi 3.0 faces two major dilemmas―how to tame the burgeoning trade deficit with China and how to screen foreign direct investment from China while striking a balance between national security and industrial policy. Both these objectives are intertwined with India’s ambition to expand its share in global supply chains. Can India steer a creative path in its economic ties with China and harvest gains?

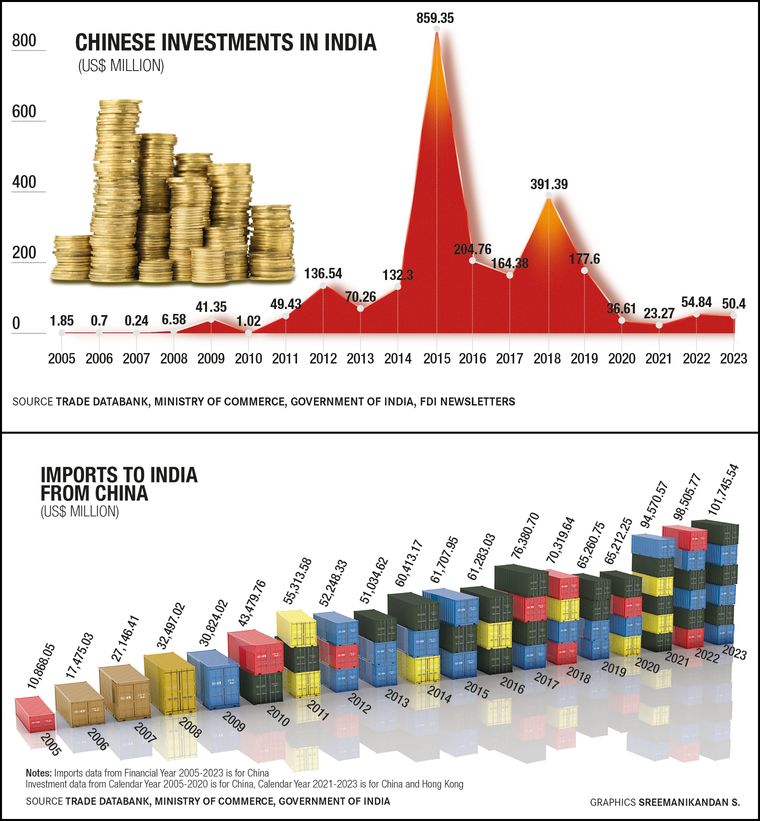

India enjoyed a trade surplus with China till 2005. Between 2005 and 2010, this turned into a $20 billion deficit. India was then importing two dollars worth of goods for every dollar of exports. The two countries then set a joint target of $100 billion for bilateral trade. From India’s perspective, this was a preemptive step to rein in the deficit by boosting exports. It was already clear that the demand for Chinese imports in India would grow without much encouragement. The target was achieved in 2021 when imports from China grew by a whopping 45 per cent in a single year. Within a year, trade deficit alone crossed $100 billion, when India’s exports stood at a paltry $17.5 billion. India is now importing almost six dollars worth of goods from China for every dollar of exports.

Ironically, this can be attributed to two triumphs of the Indian economy. One is the consumption story where growing income levels have fuelled the demand for finished products from China. Second is the success of the ‘Make in India’ campaign which has expanded India’s manufacturing sector and global exports on the back of intermediate products imported from China.

To be fair, India is not the only country with a trade deficit with China, but it stands out as a laggard when it comes to growing exports to China as a proportion of its global exports. Other major importers of Chinese products have managed to grow their exports to China to a significantly higher level as a share of their global exports. South Korea (25 per cent), Japan (21 per cent) and the European Union (10 per cent) have done much better than India (5 per cent). China’s contention that Indian exports are not competitive does not hold water since this would have stifled India’s exports to other parts of the world. The real challenge lies in non-tariff barriers unique to China’s domestic market.

Second is the investment puzzle. Economic theory suggests that direction of trade flows is an important determinant of cross-border investments. If one country’s exports to another grow substantially it is usually followed by investment flows from the exporting country to the importer country to service such demand through localisation of manufacturing. By this measure, India has not received sufficient investments from China and this might be a contributor to the oversized deficit.

Of the top 20 sources of FDI in India, excluding tax havens and oil exporters, a majority are also top sources of imports, like the US, Japan, the UK, Germany, France, South Korea and Belgium. China is an outlier here. Despite being India’s No 1 source of imports, it ranks 22 as a source of FDI.

Before 2020, when India implemented an FDI screening mechanism for Chinese investments, there were no barriers for FDI from China. Despite this, Chinese companies did not heed the ‘Make in India’ call to the extent India desired. They were distracted by other opportunities such as bidding for engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) contracts in the power and steel sectors, and venture capital investments in the digital economy. Now those doors are closed. A registration requirement has closed the door on state-owned bidders from China in public procurement tenders. There is a Himalayan divide within the digital economy after India banned more than 400 internet applications with China connections. Indian startup founders no longer hunt for cheques from Chinese VC funds.

Moving forward: An electric vehicle platform of the Chinese carmaker BYD at Auto Expo 2023 | Getty Images

Moving forward: An electric vehicle platform of the Chinese carmaker BYD at Auto Expo 2023 | Getty Images

There is growing recognition that selective Chinese investments can help India achieve multiple objectives―reduce import dependency in finished products, expand share in global value chains, receive cutting-edge technology in areas like EV batteries, hasten expansion of large-scale manufacturing and boost global exports, including to China, in labour intensive products.

The criteria applied in India’s FDI screening mechanism have been shrouded in mystery since its adoption. It proceeds on the basis that investments from countries that share a land border pose a risk to India’s national security. Unlike most other FDI screening regimes, including those targeted towards China, there is no stipulation of sectors that are considered sensitive or of permitted thresholds for shareholding and control. What little clarity has emerged through anecdotal evidence is insufficient to move the needle in the boardrooms of multinationals that dictate terms to supply chains. The purchasing power of such multinationals has managed to redirect Chinese outbound investment flows into new destinations like Vietnam and Mexico to account for geopolitical factors. These smaller countries are now saturated with FDI and do not have sufficient domestic demand to justify more. India can attract more Chinese investments of the desired type, scale and quality if policymakers articulate their preferences.

Also Read

- Can democratic India compete with authoritarian China when it comes to rapid economic development?

- Bilateral diplomacy is a never-ending tightrope walk for India and China

- China is ahead in military might, but India is catching up fast

- India must take a leaf out of China's cultural diplomacy and strengthen research on Beijing

- Both India and China use soft power to influence global opinion

- China has witnessed a vigorous crushing of civil liberties over the past decade

The last step in this strategy is for India to wangle a quid pro quo with China. Allow more Chinese investments into India of the desired sort in exchange for increased exports of manufactured items to China―a bold and gutsy Trump-style trade deal that can dislodge the current stalemate.

One may question the feasibility of these endeavours when attempts over the past 20 years have failed. However, the timing might be right owing to several factors. First, China is looking to upscale its manufacturing sector and more willing than ever to cede its domination in labour-intensive areas because of increasing domestic wages. Second, the world has lost its appetite for exclusive reliance on China and is expediting diversity in import sources. Third, Chinese companies are willing to move their manufacturing units out of China to retain their share of global supply chains. Fourth, making an investment in India is essential for Chinese companies with global market share ambitions. Fifth, China is looking to replace exports with domestic consumption as a growth driver. Lastly, the proof of concept is ready. More than 200 Taiwanese companies have taken the plunge and set up manufacturing units in India. It was Taiwanese entrepreneurs who sowed the seeds of large-scale manufacturing in China several decades ago. The wind is certainly blowing in the right direction for India.

The author is a corporate lawyer and honorary fellow at the Institute of Chinese Studies, Delhi.