The Carl Lewis versus Ben Johnson showdown in the 100m final at the Seoul 1988 Olympics remains the high point of my career covering sport. Given how events unravelled, before, during and after the race, I have not seen anything more dramatic or spectacular.

Since the modern Olympics began in 1896, the Games remain the biggest sporting event in the world. The Seoul edition carried even more significance, coming as it did after a series of major boycotts that had marred the Olympic movement.

In 1976, more than 20 African countries stayed away from the Montreal Games, protesting the International Olympic Committee’s refusal to take action against New Zealand, which had allowed their rugby team to tour South Africa during apartheid.

In 1980, America and most of the Western Bloc, numbering 65 countries, boycotted the Moscow Games protesting the USSR’s invasion of Afghanistan. This invited retaliation from the Eastern Bloc led by the USSR, adding up to more than 15 countries, which refused to participate in the Los Angeles Games in 1984.

The future of the Olympics was getting alarmingly wobbly. A reboot had become imperative for the Games to survive.

The IOC, through painstaking lobbying and astute diplomacy, worked towards getting all the countries in the world to participate in the 1988 Games. Even so, seven, including Cuba and North Korea, did not come to Seoul. However, 159 countries did.

A whopping 8,391 athletes participated. For the first time, professional tennis players were permitted to participate. The crème de la crème of sportspersons, including the likes of Edwin Moses, Daley Thompson, Seb Coe, Steve Ovett, Sergey Bubka, Florence Griffith-Joyner, Greg Louganis, Steffi Graf, Chris Evert, Vijay Amritraj and P.T. Usha, were vying for glory. A total of 739 medals were at stake, but no event was more discussed or debated than the 100m sprint featuring Carl Lewis and Ben Johnson.

Their rivalry over the preceding three years had become increasingly intense, bitter but also enthralling, capturing the imagination of the world.

Lewis, who had won four gold medals at Los Angeles (100m, 200m, long jump and 4x100m relay) to emulate Jesse Owens, was widely regarded as the greatest athlete of the time, if not all time. But Johnson, a Canadian of Jamaican origin, had begun to dent Lewis’s seemingly invincible status.

To see Johnson rise to dizzying heights over such a brief period of time was disorienting and soul-destroying for Lewis. Beaten first in 1985 by Johnson, Lewis―as indeed the whole world―thought this was an aberration. But leading into the Seoul Games, Johnson had beaten the American in marquee races a spate of times.

The 100m sprint, which identifies ‘the fastest man on earth’, is the blue riband event of the Olympics. It was also Lewis’s favourite distance.

At Seoul, his clash for supremacy with Johnson created frenzy not just among fans and the media, but also the thousands of athletes in the Games village.

The 100m final was designated the ‘Race of the Century’. Conventionally, this race is scheduled in the evening. This time, it was run on the morning of September 24 to suit television audiences, primarily in the US.

We reached the main stadium a couple of hours in advance. The atmosphere was electrifying, the excitement of those in attendance made it a scene of high-decibel cacophony. This turned into hushed whispers as the runners came into view near the starting line, then turned into pin-drop silence when they settled into their starting blocks. Johnson and Lewis exchanged a last glance at each other as they waited for the starter’s gun to go off.

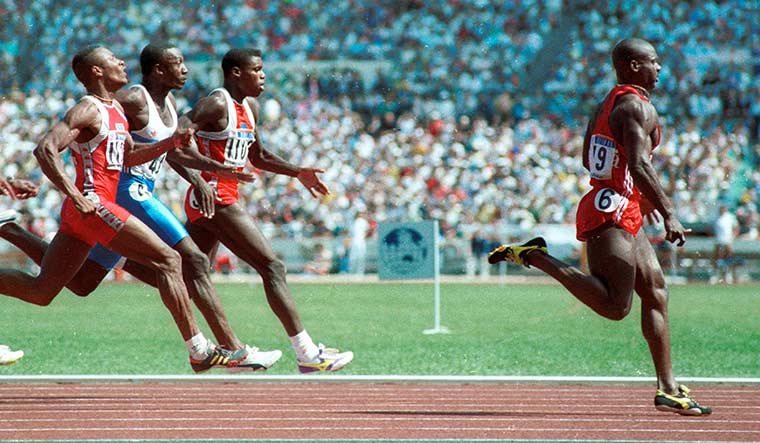

When the gun went pop, the runners were off their blocks like lightning. Within a few seconds, Johnson, muscles bulging, had surged ahead, followed closely by Lewis. Would the American be able to outstrip his nemesis? Could Johnson hold on to his lead?

Till the halfway mark, Lewis looked to be in the race. However, by the 80m mark, where we were seated, Lewis was trailing some distance behind, visibly drained of strength, his tongue hanging out as a symbol of helplessness, staring unbelievably at Johnson who powered on, raising his hand to signal triumph as he breasted the tape, the clock watch stopping at an incredible 9.79s. He had bettered the 9.83s world record he had set the previous year. Lewis clocked 9.92s, which won him the silver but seemed pedestrian in comparison.

The stadium broke into bedlam. The media precincts became the hub of frenetic activity as reporters, writers, photographers and broadcasters flailed over each other to be the first with their dispatches.

My day had started at 5am, to go to the race. It ended around midnight, after the last story had been filed. It had been a daunting, tiring day, but also hugely fulfilling. As I put my head on the pillow to sleep, I told myself how fortunate I was to be at the Olympics. Could there be a bigger story than seeing the Race of the Century!

Also Read

- Paris Olympics know your athlete: Aditi Ashok can finish on the podium, but a good start will be key

- Paris Olympics know your athlete: Saikhom Mirabai Chanu cannot be written off, despite injury woes

- Paris Olympics know your athlete: For wrestler Vinesh Phogat, the personal is the political

- India at Paris Olympics 2024: Vadlejch, Peters await Neeraj Chopra’s javelin gold defence | Know your athlete

- India at Paris Olympics 2024: How steeplechaser Avinash Sable peaked ahead of Games | Know your athlete

- India at Paris Olympics 2024: Shooter Sift Kaur Samra can wipe memories of India's dismal Tokyo outing | Know your athlete

Around 5am, I was woken up by furious knocking on the door of my room in the media village. “Ben Johnson has tested positive for drugs,” said a journalist whose name and nationality I cannot recall now. “He is on his way to the airport to be flown back to Canada.”

By this time, word of Johnson being nabbed by a lab assistant for taking the banned substance stanozolol was no longer exclusive information. As word spread, pandemonium broke out in the media village with reporters making a beeline for either the airport or to catch Johnson, or the media centre to chronicle this remarkable twist in the tale; of how Johnson, who had the world at his feet in the morning, had the ground cut from under him by evening,sent to his doom by an ordinary but alert lab assistant.

The race of the century had become, as the title of writer Richard Moore’s tour de force account of the Johnson-Lewis rivalry describes, The Dirtiest Race in History.