From trying to prove that Indian dominance in an athletics event was not a fluke to vying for a third individual Olympic medal, the Indian contingent at the Paris Olympics is full of varied arcs

he first batter to score a century in the Ranji Trophy, S.M. Hadi, had played tennis for India at the 1924 Olympics. So did a criminal lawyer from Cambridge and a medical doctor from London. None of them, or the 10 others they accompanied to Paris, won a medal.

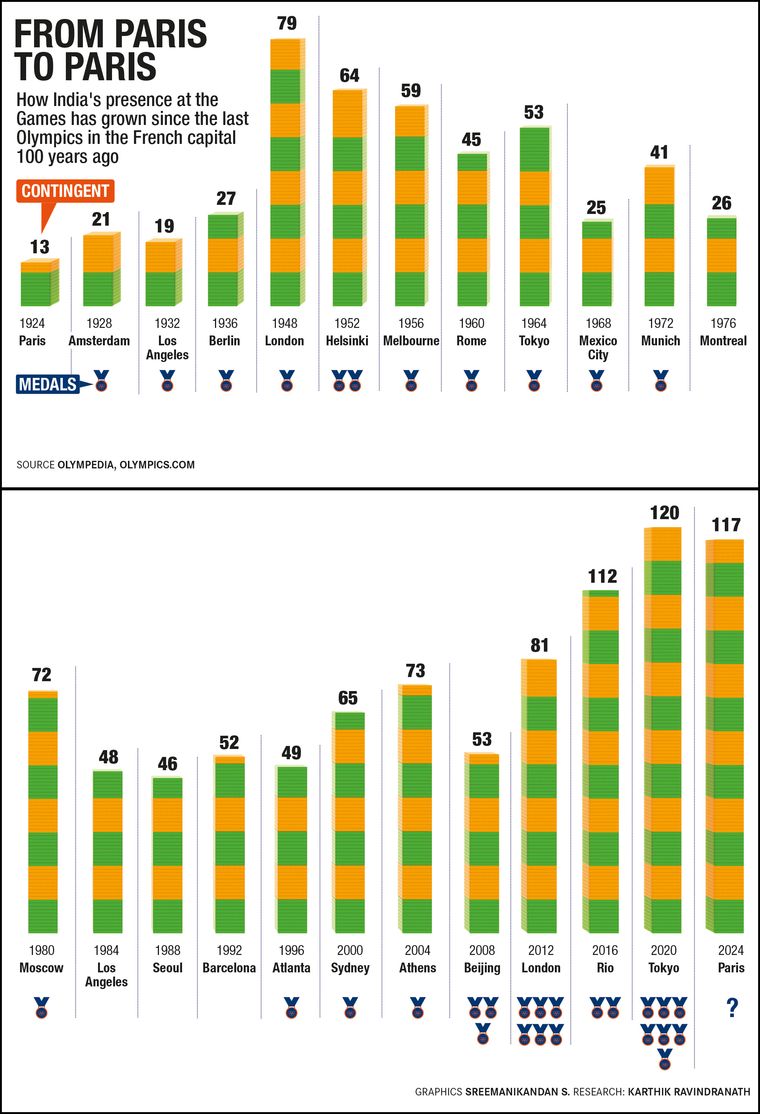

Exactly a century later, as India sends 117 athletes to the Games, once again in Paris, there is at least one solace. None of them has a PIL to file or a patient with a tummy ache to care for. They are all in. And they are all hungry. Some because this will be their last dance at the Olympics, some because it will be their first.

For Neeraj Chopra, another medal in Paris would prove that, yes, an Indian can dominate world athletics and that the throw in Tokyo was not a ‘pinch me’ moment. That the high his gold gave Indian athletics was not fleeting, and that there are now others stepping up their game.

Ask the 4x400m men’s relay team. In the past year, the team of Muhammed Anas, Amoj Jacob, Muhammed Ajmal Variyathodi and Rajesh Ramesh have won gold at the Asian Games―the first Indian team to do so since the days of Milkha Singh―and have broken the Asian record by clocking in at 2.59.05 in the heats at the World Athletics Championships in Budapest in August 2023. In an incredible feat, they finished fifth in the final.

“From an Indian perspective, we need to go past measuring success with medals,” said Manisha Malhotra, former tennis player and head of sports excellence and scouting at JSW Sports. “I do believe we are in a very good place heading into Paris. The Indian contingent is a lot younger, and many of our athletes have spent a lot of time competing and training abroad. Some have also won multiple World Championship medals and that is cause for all of us to be hopeful.”

Perhaps athletics might not get India many medals, perhaps only Chopra would get to the podium, and even that is not guaranteed. The real measure of progress, however, would be to see how many Indian athletes make it to the final of their events. In that, the nation might see some bright spots.

But if medals are the barometer, then India has to cross seven, the tally in Tokyo. And for that, the shooters would have to be on target. Three years ago, the group of world beaters returned empty handed from Japan in what was a morale-crushing outing.

Locked and loaded: Manu Bhaker would look to lay the ghost of Tokyo to rest in Paris | PTI

Locked and loaded: Manu Bhaker would look to lay the ghost of Tokyo to rest in Paris | PTI

Manu Bhaker took it particularly hard. The talented shooter from Haryana had been excellent leading up to the Olympics, but her weapon malfunctioned in the qualification round of the 10m air pistol, and that set the tone for the rest of the Games.

“It was just bad luck,” said Sift Kaur Samra, the world record holder in 50m Rifle Three Positions. “I was not part of that team, but I know that they gave it their 100 per cent. I think if you do not keep expectations, then you just go with the flow and enjoy [shooting].”

Bhaker is back at the Games in Paris, and has reunited with coach Jaspal Rana after a falling out in 2021. She seems to have put behind what happened in Tokyo, and will have three chances to medal in Paris―women’s 10m air pistol, women’s 25m pistol, and 10m air pistol mixed team.

“In what may sound like a mix of optimism and confidence, I will say that India could surpass the seven medals from Tokyo,” said Rushdee Warley, CEO of Inspire Institute of Sport, one of the country’s top coaching and training centres. “Of course, this is sport, and everything needs to go perfectly right on the day, along with a little luck. But if things stay true to form, I feel India could see its highest ever tally at an Olympic Games.”

What could work for India is simple maths. The nation has sent its largest-ever shooting contingent to the Games this time. If Tokyo saw 15 Indian shooters, Paris will see 21. More athletes, more chances.

“To be frank, shooting is a difficult sport; it has very fine margins and anyone can win or lose on a certain day,” said Malhotra. “We’re going in with a very strong and very different contingent and I have big hopes for shooting. I believe we should be able to win five medals, but I think three would be more realistic and would be a good performance. These are young kids, not many big names or big personalities, and I believe that is going to be the big story in Paris.”

It could be the big story, but heading into the Games, there are stories galore in the Indian camp. Like P.V. Sindhu’s quest to become arguably the greatest individual Olympian from India. She already has a silver and a bronze, and if she can add another medal here, she becomes the only Indian in an individual sport to collect three―a couple of men from India’s golden generation of hockey have four.

Sindhu’s form leading up to the Games might not inspire any medal talk; she has made only one final in tournaments this year. Plus, she turns 30 next year.

However, this is an athlete known to step up. “She has always been a big tournament player,” said H.S. Prannoy, Sindhu’s squad mate. “No matter what happens in the entire year of Super Series events, when it comes to the big events, she is able to deliver. I’m hoping she gets into that mood once again.”

In what might surprise many, this is Prannoy’s first time at the Olympics. The veteran had a stellar 2023, winning bronze at the World Championships and the Asian Games, but frequent bouts of ill health scuppered his progress. He was down with chikungunya just weeks before the Games, but as soon as he recovered, he was back on the court. His focus now is on increasing his speed to keep up with the young legs on the circuit. For Prannoy at Paris, it is better late than never.

Fellow Malayali P.R. Sreejesh knows that feeling. He had it last time; it was his third Olympics. At Tokyo 2020, India won an Olympic medal (bronze) for the first time in 41 years. Sreejesh was instrumental in that campaign.

And now, as he walks into the sunset after these Games, he leaves behind a team that a nation has rallied behind, and one that is in the process of restoring the glory that Dhyan Chand and his men had achieved.

When THE WEEK spoke to hockey captain Harmanpreet Singh last August, he said the dream was to get automatic qualification into the Olympics by winning gold at the Asian Games in Hangzhou. They ticked off that box, but a bigger one awaits.

“Coming into a tournament, you have got an ideal goal and a realistic goal,” coach Craig Fulton told THE WEEK ahead of last year’s Asian Games. “The ideal goal is always to win. The challenge is: what is the realistic goal? How were you performing consistently in the last six months and what are you doing currently?”

In the past six months, India has not had a great run. They have had more losses than wins, including the 0-5 defeat in the series in Australia. Plus, India is in a tough pool with Australia, Belgium, Argentina and New Zealand.

Given that little separates the top teams in hockey at the moment, and anyone can beat anyone, getting a good start will be crucial.

“The whole nation has a lot of hopes from the hockey team,” said Hockey India president Dilip Tirkey, himself a stalwart of the game. “The way the team has been playing under coach Craig Fulton after the 2023 World Cup (where India got knocked out early) has been good. Sreejesh and Manpreet are playing their fourth Olympics and Harmanpreet is captain. We have a lot of hope. The team will have to focus on short corners and defence.”

Defence, though, is not Aman Sehrawat’s preferred strategy. The 21-year-old likes to be on the attack, which complements his high speed.

Coming out of the turmoil that India’s wrestling scene has been in recently―what with the allegations against former Wrestling Federation of India chief Brijbhushan Singh and the wrestlers’ protest at Jantar Mantar―Sehrawat became the only male grappler from India to qualify for the Paris Olympics. Apart from 2016, when Sakshi Malik won bronze, the men have delivered medals for India in every Olympics since 2008.

Sehrawat’s path in the 57kg category went through his idol and Tokyo silver-medallist Ravi Dahiya, whom he beat in the race for the quota. Sehrawat is, along with Antim Panghal in the women’s 53kg category, the only Indian wrestlers with a seeding at these Olympics. This means they would avoid tougher draws till later in the tournament.

The big question, however, is whether the mess within the federation would end up costing India on the mat. “To some degree, I do believe the timing of the events off the mat, and to have no federation in place and nobody calling the shots, have affected performance,” said Malhotra. “That being said, we should have been able to manage and grow the sport. Everyone was so quick to sideline the progression and there were so many political systems at play that we have not done what is best for the sport.”

In essence, it would seem that whatever medal India does win in wrestling, would most likely be in spite of the system rather than because of it.

Another sport where the women will hog more of the limelight is boxing. Two-time world champion Nikhat Zareen (50kg) and Tokyo bronze-medallist Lovlina Borgohain (75kg) are in the fray, with the former competing in her first Olympics.

Borgohain will have the experience of having done it before as she steps into the ring in Paris. That she won gold at the Women’s World Boxing Championships last year in Delhi and later silver at the Asian Games in Hangzhou has boosted her reputation heading into these Games. It also validated her switch to 75kg from the 69kg category, which the International Boxing Association dropped from the Paris Games.

The competition, however, is strong with names like China’s former world champion Li Qian, whom she has had no luck against recently, and the refugee team’s Cindy Ngamba, who beat Borgohain in the Czech Grand Prix this June.

But up for grabs for the Assamese boxer is the chance to create history by becoming India’s first double medallist in the sport. The country so far has three medals in boxing―one each to Vijender Singh, Mary Kom and Borgohain.

But the fact that an athlete winning two medals becomes historic in India also points to where the nation stands at the moment. While crossing the medal tally from Tokyo will and should be celebrated, it is worthwhile to remember that India at the Olympics is still a work in progress.

For in India, there has been a romanticisation of the struggles athletes overcome. Ideally, they should not be facing struggles that are not sport-related, in terms of money or opportunity. “I could not agree more,” said IIS’s Warley. “Yes, Indian sport is rife with stories of athletes coming from difficult backgrounds and making it big, and while we might not be able to affect the genesis, it is down to the system to identify, harness and support these athletes once they have been taken into the fold. A robust public-private-partnership model goes a very long way in making sure we do not lose talented athletes to lapses that stem from limitations.

“At the IIS, the effort is constant to ensure that we are giving our athletes the best chance to succeed. Many of our Olympics-bound athletes have been training across the world in the build-up to the Games. There are other private organisations, too, doing their bit, and the results are there for all to see. However, we will need a dozen more IISs if we are to bridge this gap.”

Also Read

- Paris Olympics know your athlete: Aditi Ashok can finish on the podium, but a good start will be key

- Paris Olympics know your athlete: Saikhom Mirabai Chanu cannot be written off, despite injury woes

- Paris Olympics know your athlete: For wrestler Vinesh Phogat, the personal is the political

- India at Paris Olympics 2024: Vadlejch, Peters await Neeraj Chopra’s javelin gold defence | Know your athlete

- India at Paris Olympics 2024: How steeplechaser Avinash Sable peaked ahead of Games | Know your athlete

- India at Paris Olympics 2024: Shooter Sift Kaur Samra can wipe memories of India's dismal Tokyo outing | Know your athlete

In 1924, Dorabji Tata had personally paid for most of the Indian contingent’s expenses and, a few years after, helped set up the Indian Olympic Association.

The field is much larger now. “Corporate investment is key because of two reasons,” said Sanjay Adesara, chief business officer, Adani Sportsline. “For starters, the athletes need a support system because sport is expensive and second, associations of this nature and magnanimity always helps the growth of the brand. Therefore, it is a win-win in that sense.”

The emergence of corporate help does not mean that the government has done nothing, as Union Sports Minister Mansukh Mandaviya explains in an interview (page 48 ).

Hockey, for instance, has been associated with the Odisha government for a few years now. “With Hockey India going sponsor-less, the Odisha government felt the need to get into that role so that the emotional connect [of hockey] with Odisha and India can be restored,” said Ranjit Parida, joint secretary, sports and youth services department, Odisha. “So that story actually began from the concerted effort of the Odisha government to support hockey.”

The progress, though, is still a jog, not a run. “We are still nowhere when it comes to track and field, cycling, rowing and swimming, which [offer] the highest [number of] medals. There is a big space for improvement and, for us to be able to factor in the growth in medals, it has to be a very strong system, which we do not have at the moment. We are currently investing in individual athletes, and that will not give you a sustainable long-term model.”

Perhaps that is the benchmark; being known for dominance in a sport rather than being known for an athlete who dominates the sport. Dhyan Chand’s men would agree.