IN THE MID-1800S, four brothers of Vadluru village near Tanuku in present-day Andhra Pradesh began a long walk to Varanasi, India’s spiritual capital. After mastering Hindu scriptures there, they returned home and began sharing their knowledge with the villagers. The brothers came to be known as ‘Chilukuri Chatushtaya’―the four pillars of knowledge of the Chilukuri family.

“They were erudite and proficient in Sanskrit,” says Chilukuri Shanthamma of Akkayapalem in Visakhapatnam. Shanthamma’s husband, Chilukuri Subramanya Shastri, is a grandson of one of the ‘Chathushtaya’.

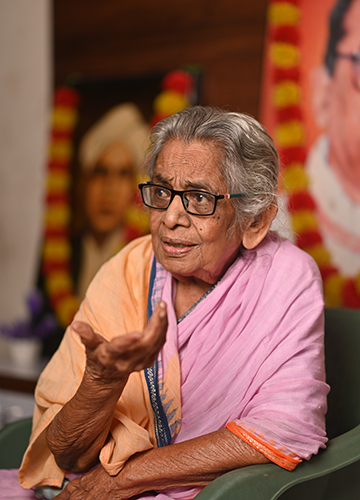

At 96, Shanthamma looks spry even though she cannot move around without walking sticks. She jogs her memory when talking about her illustrious family, whose members include eminent teachers who have shaped India’s academia. The family’s latest newsmaker, though, is someone who is settled abroad―Usha Vance, lawyer and wife of J.D. Vance, the Republican Party candidate for US vice president. Usha is a Chilukuri―she is the granddaughter of Shanthamma’s husband’s brother; her family had migrated to the US in the late 1970s.

Shanthamma’s husband was a professor, as was her brother-in-law. Her father-in-law was the headmaster of a local school. Shanthamma specialised in spectroscopy and vedic mathematics, and claims she is the first woman to hold a PhD in physics in India. She is now professor emeritus at Centurion University at Vizianagaram, and has translated the Gita from Telugu to English and written five volumes on vedic mathematics.

Shanthamma’s second-floor apartment at Akkayapalem reflects her spartan life. The drawing room has plastic chairs and a teapoy, besides a divan and a TV stand. She proudly says she does not have diabetes or blood pressure. “I have not undergone surgeries, too,” she says. “I just have a hearing problem; so you have to talk louder.”

She turns her attention to a set of framed photographs on the TV stand. One of them is of her paternal uncle Deekshithulu, who was a judge in Machilipatnam during the British rule. Shanthamma’s father died before she was born, and it was Deekshithulu who took care of her. “He gave me shelter, clothed me, and gave me an education,” she says.

Shanthamma moved to Visakhapatnam with Deekshithulu’s family. She graduated from Andhra University, where she later served as a professor of physics until her retirement. “I believe in the power of positive thinking,” she says, glancing at a portrait of her mother. “She was also like that. Though she lost her husband when she was 20, she lived till 104.”

She looks at the photo of her late husband, Subramanya Shastri, a Telugu professor at Andhra University who, she says, once declined an opportunity to migrate to the US citing of his love for India. Shastri was known for his mastery of the Gita and the Telugu language. “He was a wonderful person,” she says.

During the Emergency, Shastri was jailed for his links to the RSS. “He was there for two years,” she says. “He taught lessons from the Gita in jail.” The classes, apparently, were so impressive that a prison department officer had a session with Shastri after the Emergency was over.

Between 2000 and 2005, Shastri worked as RSS leader in not just Andhra Pradesh, but also Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Odisha. He and Shanthamma donated their residential property, estimated to be worth around Rs15 crore now, to the RSS-affiliated Vivekananda Medical Trust. They got a token amount in return, with which they bought the flat where Shanthamma now lives. The couple did not have children; Shastri died nearly a decade ago.

Shanthamma now lives with a couple and their two children. “They take care of me, and I take care of them. I cook their lunch, and they cook breakfast and dinner for me,” she says.

Every day, her driver takes her to the university, 70km away. “Lord Krishna said that we were born to do our job. I am doing it,” she says.

G.S.N. Raju, chancellor of Centurion University, says she has “100 per cent attendance”. “She is never on leave…. She is more updated on the latest academic topics than others in the faculty are,” he says. Raju was Shanthamma’s student at Andhra University.

Shanthamma’s brother-in-law Ramashastry, Usha Vance’s grandfather, was one of the most accomplished members of the Chilukuri family. Ramashastry taught at IIT Kharagpur and IIT Madras, where he was also the head of the department of physics. “He worked in one of our labs at Andhra University and then left for Kharagpur,” says Shanthamma. “He developed labs, developed people and, like me, stayed on and taught till the end.”

Also Read

- It is unlikely that Trump will change his 'combative' mode of campaign as he targets Harris

- Kamala Harris hopes her roots, legal background and pro-women record will help her beat Trump

- Indian American voters are jumping on to the Lotus Potus bandwagon

- Joe Biden's call to leave the race is perhaps the most important legacy of his presidency

- Republicans are recalibrating their campaign to counter Harris: Ambassador K.C. Singh.

- Campaign finance in the US looks transparent, but may not be really so

During his stint at IIT Kharagpur, Ramashastry was sent on deputation to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for two years. At IIT Madras, he also led an Indo-German collaboration in the 1960s to set up a state-of-the-art physics laboratory. There is an award at IIT Madras named after him for his contributions.

Ramashastry’s son Radhakrishna is also an IIT Madras alumnus. He migrated to the US for higher studies and later became a lecturer at San Diego State University. His daughter, Usha Chilukuri, was born in 1986. Usha met J.D. Vance while she was a student at Yale Law School. The couple got married in 2014.

Shanthamma has been to the US twice, but has never met her grandniece, who is now a high-profile lawyer with a shot at becoming the Second Lady of the US. She says she is worried about the “brain drain” from India to the US.

So what would Shanthamma say if she crosses paths with Usha in the future? “I would say, ‘Don’t allow Indians to stay there.’ Let [them] for some time, [for giving them] a better chance to learn,” she says. “They should not go there for money and enjoyment. Usha has to help Indians this way.”