THE CONGRESS’S POLITICAL narrative that the BJP and Prime Minister Narendra Modi were on a downhill journey―post the 2024 Lok Sabha elections―could not get the much-needed endorsement from voters in Haryana and Jammu and Kashmir.

The results have shown that a large section of voters might not have been satisfied with the BJP’s performance, but, at the same time, they did not repose confidence in the Congress to be a viable alternative, with its excessive reliance on the farmers’ protests and efforts at social engineering around caste. The political narrative was not in convergence with the logic of social dynamics. By way of counter-mobilisation, the BJP stoked memories, such as anti-dalit violence in Mirchpur in 2010 and a violent Jat agitation that targeted non-Jat businesses, which led to a Jat-focused, high-pitch campaign. And, as a result, only 13 of 27 Jat candidates of the Congress won.

The AAP, which claimed to be a party with a difference and ran a massive media campaign showcasing its performance in Delhi and Punjab, could get only under 2 per cent of the votes. It is claimed that this vote share might have hurt the Congress in three to four seats. But the voters are not herds, they are social beings bound by their everyday survival needs. For the BJP, the third consecutive win in Haryana is an achievement. And peaceful elections, with a 64 per cent turnout, holds the message that the people in Kashmir firmly believe that democracy is the only antidote to violence.

A GLANCE AT THE RESULTS

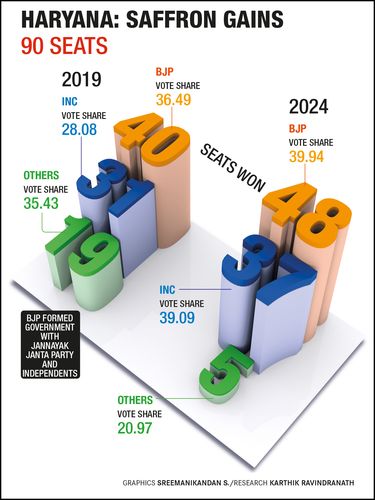

The Haryana results clearly demonstrated the polarisation among the Jat and non-Jat voters. The BJP had an edge with around 59 per cent strike rate in non-Jat dominant regions, whereas the Congress had an edge with the Jat peasantry with 48 per cent strike rate. It clearly reflects the non-Jat consolidation in favour of the BJP.

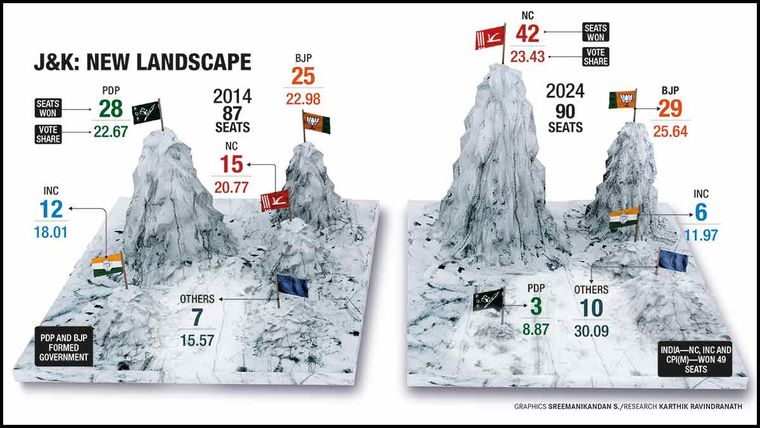

And in Jammu and Kashmir, identity politics related to religion and the regions―Jammu and Kashmir valley―played a crucial role. Of 43 seats from the Jammu region, the BJP won 29. The National Conference secured 41 seats from the Muslim-dominated Kashmir valley.

FROM COALITION NURTURING TO POWER COALITIONS

HARYANA

The BJP in Haryana was already the dominant party, which approached electoral alliances more selectively, focusing on maintaining dominance rather than building coalitions to win elections. It changed its stance from alliance builder to power consolidator.

The BJP’s strategy shifted towards a more self-reliant model, focusing on leveraging its own national dominance. Its ability to win elections on its own, particularly in the non-Jat heartland, reduced the need for a large pre-poll alliance. However, it left the door open for post-election partnerships to ensure smoother governance or support in regional legislative bodies.

The Congress has of late been more flexible in its ideological partnerships, focusing on pragmatic alliances with regional parties to stop the BJP’s dominance. But, in Haryana, it decided not to enter a pre-poll alliance with the AAP and tried to leverage regional strengths on its own to defeat the BJP.

JAMMU AND KASHMIR

The Congress entered a strategic alliance with the National Conference as it could observe that the voters in Kashmir support regional parties overwhelmingly. In Jammu, the voters were sceptical of the Congress and its alliance with the NC. The voters who see the Congress as a counterbalance to the BJP’s policies might have voted for this alliance.

The NC alliance with the Congress helped consolidate significant percentage of votes for the NC vis-à-vis other contestants like the PDP.

The BJP presented itself as a force to maintain peace, harmony and development. There were not many takers of this promise in the Kashmir valley. The voters in Jammu, however, harbour a grievance that the NC government in the past favoured Kashmir in terms of resource allocation.

These results in Jammu and Kashmir will push the radical sections to the margins. People’s disillusionment with violence as a mode of achieving goals was visible in the villages of Kashmir. Iklaq, a shopkeeper in Anantnag’s Hanjan village, said that the demand for ‘Azad Kashmir’ was now history, but he lamented that, at the level of politics, the issues of livelihood, jobs and infrastructure development get drowned in the fight between Hindus and Muslims, and between Jammu and Kashmir.

The election results have shown that instead of azadi, identity or autonomy, people are more concerned about the basic issues of survival, which include clean water, roads, jobs and health care facilities.

For the NC, the challenge would be to integrate, politically and economically, the two regions and allocate resources to Jammu despite the fact that it voted for the BJP. Democracy is the only antidote to terrorism. And development and distributive justice are the only hope for the survival of democracy. NC president Farooq Abdullah observed that they had to tackle inflation and unemployment, and that all 90 members of the assembly shall work together to rebuild Jammu and Kashmir.

For the Centre, it would be politically prudent to grant full statehood to Jammu and Kashmir. This would give a fillip to the rural economy, which appeared to be stagnating with production being only for subsistence and not for the market, besides providing subsidies for the apple growers as per the Himachal Pradesh model and setting up agro-processing units.

ISSUES, CAMPAIGN AND STRATEGY

Leaders in the fray seemed to have covered every possible local concern ranging from caste reservations in jobs, both in the private and the public sectors, to women’s employment. This became a rallying point as caste equations directly impacted the election results, particularly in Haryana.

The rhetoric of political parties, that they would liberate people from poverty, inequalities, unemployment, crony capitalism and food inflation, etc., is seen by voters as ritualistic theatrical performances by competing political actors.

In the midst of rising expectations, with social media nurturing an aspirational class, populism becomes a potent tool to connect with the voters. For instance, the agenda of political parties to provide freebies to the voters as entitlements merited their attention. In its manifesto, the BJP promised monthly assistance of Rs2,100 for women, two lakh government jobs for the youth and guaranteed government jobs for Agniveers from the state. It also declared that it would procure 24 crops at MSP.

The Congress also announced seven guarantees, including promises of a legal guarantee for MSP, a caste survey, and Rs2,000 per month to women.

In Jammu and Kashmir, the political discourse was largely articulated within the manifest forms of tensions like abrogation of Article 370 and restoration of statehood, rather than issues relating to livelihood.

A major narrative in this election was centred on change (badlaav), with opposition parties, especially the Congress, pushing for a shift in governance after nearly a decade of BJP rule. The BJP emphasised the fear of Jat dominance under the Congress to rally non-Jats, while the dalit votes also played a crucial role, with several alliances aiming to split the vote.

The BJP has traditionally attempted to consolidate the OBC vote by promoting non-Jat leadership, such as its new chief minister, Nayab Singh Saini, an OBC. The party could unite OBCs and upper-caste communities, who hold political significance, especially in the non-Jat-dominated areas.

The opposition targeted the BJP over the handling of the economy, citing price hikes in food, fuel and agricultural inputs, which have hurt both urban and rural populations.

The 2020–2021 farmer protests against the now-repealed farm laws still linger in Haryana. They continue to protest the Centre’s agricultural policies, accusing the BJP of not legalising MSPs.

REASONS FOR THE CONGRESS’S DEFEAT IN HARYANA

The main reason for the loss, as stated before, was the consolidation of the non-Jat votes and the factional feud between Jats and scheduled castes.

Also Read

- Jammu-Kashmir and Haryana assembly election results: Dear politicians, hear the people's voice

- J&K: Abdullahs return to power after 16 years, but Omar will have to walk the tightrope

- 'Election result a rejection of what BJP has done to J&K': Omar Abdullah

- How BJP beat anti-incumbency in Haryana

- How BJP is working to consolidate its future after Lok Sabha debacle

- Haryana and J&K results come as a reality check for Congress

The faction-ridden Congress and the impact of the public feud between Kumari Selja, a dalit leader, and the state leadership of Bhupinder Singh Hooda, led to a large section of the rural dalit vote bank shifting to the BJP. The BJP carefully appropriated it. The government of Haryana announced that it will divide SCs into deprived scheduled castes (DSC) of 36 groups such as Balmikis, Dhanaks, Mazhabi Sikhs and Khatiks, and other scheduled castes (OSC) consisting of Chamars, Jatavs, Rehgars and Raigars, among others. The government decided that DSCs would have an internal reservation of 50 per cent within the SC quota.

The division influenced the vote shift from those of the second-largest SC community in the state, the Balmikis, to the BJP. This not only helped in the reserved seats, but built a narrative in support of the BJP.

For the Congress, losing key states like Haryana, where it has had a strong foothold, would dent the party’s image. This could create an impression of the waning prospects of the Congress’s emergence, which may embolden the BJP and the regional players in Maharashtra to intensify their campaigns against the Maha Vikas Aghadi.

The writer is chairperson, Institute for Development and Communication, Chandigarh