Interview/A.R. Rahman, musician

Two or three decades ago, it would have been unthinkable to get A.R. Rahman to agree to a quick interview, let alone have a leisurely chat after work. He was the musical genius who was heard more than seen, with his public interactions limited to a smile and a brief “thank you”. Today, though, Rahman is a skilled conversationalist―sharing his feelings, explaining his thoughts, and cracking jokes and laughing heartily. He has also become skilled at posing for photos, adept at finding the right angles that show himself exactly how he wants to be seen. “Yes, I am getting better at it. Part of the job, right?” he smiles.

Our interview begins late at night and stretches past midnight. His assistant tells me this is when Rahman is at his best, mentally and physically. Throughout the day, he is busy with recordings, events and meetings with film producers. Yet, as his SUV pulls into the studio, which also doubles as his multi-storey bungalow in Chennai, he looks as though his day has just begun.

Right next to the studio is a simple pet corner with a green mat, a small toy slide, a ball and a food bowl for the cats that frequent the space.

We grab mugs of hot black coffee before sitting down for our chat. Piping-hot biryani, ordered from a nearby restaurant, awaits us for dinner. “This interview has become as long as a Hollywood film,” he quips.

Our conversation flows freely, without inhibitions, covering the Oscar-winning musician’s life―from the intense ambitions of the 1990s and early 2000s to the more perceptive composer he has become in the last two decades, to the tech innovator he is evolving to be. Despite his accolades, Rahman does not write “Oscar-winning musician” on his X bio―he simply updates it with his current project. “That was my past, but I live in the moment,” he explains.

He has never been more content with himself, he says. “This has to be my best decade so far, and now I am making music that makes me happy. The desire to give back, to leave something that will inspire future generations, has never been stronger. I am constantly thinking about what more I can do, what more I can contribute,” he says.

At the start of our conversation, he made it clear: “Please don’t use grand words to describe me. I’m no ‘Mozart of Madras,’ and I am not some fancy authority. Please keep it simple; just use my name.”

Edited excerpts from the interview:

Q/ The Rahman I see today is very different from the one I grew up listening to as a millennial. Director Mani Ratnam calls you a style icon. What has led to this transformation?

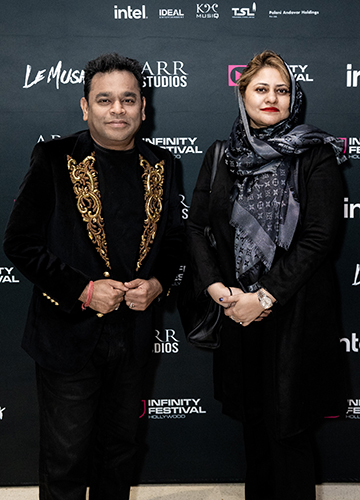

A/ Yes, that’s true. Earlier, I believed in letting my work speak for itself, and I still do to an extent. But since I have become a part-writer who tells stories, I have improved my vocabulary and articulation. Also, after winning the Oscars, I realised that if people are looking at you, from India, you can’t remain silent―you need to open up, dress up…. So, from a third-person perspective, I thought, ‘Okay, things have to change.’ My wife, Saira, deserves all the credit for it; she shops for me, styles me, and is my everything.

Q/ You have been exploring emerging technologies―penning a virtual reality thriller and working with the latest technologies in music. Does stepping into unknown territories come naturally to you?

A/ Music is such a vast ocean, and sometimes it feels like I haven’t even scratched the surface of what’s possible. People find formulas all the time, and even I find myself trapped by repetition even though I try to avoid it. After I have done something, I could easily capitalise on it tenfold, but I want to move on. It is important to stay passionate about what excites you. I am sleepless, and I am constantly texting people asking how things are done, because I am eager to know the possibilities. A question that is very important to me is, why can’t Indians innovate like they do in the west? We may be good at certain things, but art is definitely not one among them.

Q/ You ventured into virtual reality, much ahead of its time. Is India ready to embrace it now?

A/ For me, it was about doing something that I have not done before. The 37-minute VR film Le Musk is not just a story; it is an immersive experience with scent, art, psychology and spirituality all bundled together. I have had people say they didn’t want to return to the real world, which is the highest compliment I have received.

Although it began with a casual conversation with my wife, who enjoys perfumes, the main trigger was boredom with the traditional film formats. We have been watching films on rectangular screens for more than a hundred years, and it is time to move on and make the experience more immersive. [Le Musk integrates] a scent module, haptics, 3D and 4K 360-degree [visuals] and cutting-edge sound.

Q/ Is the output as you envisioned?

A/ It was not easy. In film and music, there are countless people working on software and technology, and it is essential to stay updated. A 2D filmmaker can never understand [VR] tech. I didn’t know anything about 2D filmmaking, so I set up my own work flow and set of cameras for close-up, mid shots and all that stuff. We now have a set of 21 cameras, one for each need.

We shot the film in Rome and released it in two months on a streaming platform. We faced a lot of challenges, but I kept my team motivated. We released teasers and showcased a shortened version at Cannes. We did the final cut a year ago, with even more tech involving sound and scent. Unfortunately, only around 1,000 people in the world have been able to watch it; those VR chairs are not easy to come by here in India.

Q/ Your ambitious project, Secret Mountain, is being hailed as the future of entertainment.

A/ Secret Mountain is also a band from India. We have had amazing musicians like Pandit Ravi Shankar, Anoushka Shankar and Zakir Hussain, but we have never had an internationally recognised band. After ‘Jai Ho’ [from Slumdog Millionaire], I took a year off to chill out. I had the idea to form a band in Los Angeles that was multicultural, so I auditioned musicians from Berkeley. But then my mom fell ill, and I had to return. But the idea stayed with me.

And then I saw the progress of Unreal Engine and MetaHumans (Unreal Engine is a digital platform where users can create and animate highly realistic digital human characters, called MetaHumans), and I thought, ‘This is it!’ You are no longer trapped by your skin colour; you can be anything.

We now have mentors from Africa, Ireland, China, America and India, and singers from Africa, Ireland and Mongolia. I have been having the time of my life working on this, even as the technology in this domain is growing in leaps and bounds every week. Mind you, this is not artificial intelligence; it is a collaborative effort where a lot of people work on each character.

Q/ What about the potential of AI?

A/ AI is Frankenstein―trained on collected, stolen knowledge. [It] is good as a starting tool. I use AI for posters. Sometimes the result surprises you, and sometimes it is very bad, in which case I use a combination of Photoshop and AI.

Q/ How do you use AI in music?

A/ AI helps in the mastering process, but creating a tune still requires a human heart and philosophical mind. I believe the future will belong to real musicians going on stage with a guitar and a song…. I feel that, with digitisation, we will value the flaws even more―‘Oh, it’s real, see? He is out of tune.’

Q/ You recently used AI to recreate the voices of late singers Bamba Bakya and Shahul Hameed, for a track in the Rajinikanth film Lal Salaam.

A/ I was watching people recreating famous singers on Instagram when Aishwarya (director Aishwarya Rajinikanth) asked for a folk voice. I said I wished we had a voice like Shahul’s. We reached out to his family, got their approval and compensated them fairly. It is a great way to honour them, rather than just taking their work.

Q/ In India, how far do we need to go to fully utilise future technologies?

A/ Beyond technology, we need to invest in talent and in collective creations. Musical theatre is virtually nonexistent here, except for NMACC (Nita Mukesh Ambani Cultural Centre) in Mumbai…. We don’t have world-class load-ins (the facilities for setting up all equipment and material needed for a production)…. We are trying to set up a state-of-the-art space in Chennai, with guidance from international experts.

Q/ You mentioned the urge to innovate in every decade.

A/ Every three years; not every decade. If I don’t do something new every three years, I feel like I am rotting.

Bahauddin sahab (the rudra veena exponent Bahauddin Dagar) once told me that each of us has a different mental makeup. I was focused on mastering a raga for three years before learning another. One has to go deep into certain things.

Some directors are knowledgeable, like [K.] Balachander, Raja [Krishna] Menon… Mani Ratnam has a keen ear for everything. When he hears it, he gets it. So I keep telling people who say that (directors) are not letting them do it, ‘Why don’t you show them, instead of telling them, that you are going to do a Bilaskhani Todi?’.

Your investment is not waiting for somebody to commission you. You commission yourself, and you do things so that people know what you are capable of doing. Luckily, I have been learning by doing movies and getting paid for it. It is a great way to learn―you get paid and you test out what the audience like and don’t like. And then you learn more.

Q/ Mani Ratnam says your way of working is very instinctive. You first make the music and, if he likes it, he places it in the film.

A/ I have seen composers approach scenes in certain ways. [With those ways], scenes trigger muscle memory in me. So, to challenge my instincts, I try something entirely different. With the director’s help, we place [a musical piece] in the movie and see how it pans out. We just wildly put it in some place and magic happens. That’s what happened with Roja.

Q/ From Taal and Rang De Basanti to Raanjhanaa, Atrangi Re and Aadujeevitham, you have grown and evolved.

A/ My work is like a capsule―the outer layer changes, but the core is the melody. Can the tune stand on its own, is what I assess. The audience responds to compositions that are grounded.

Q/ You collaborated with Hans Zimmer. How was the experience?

A/ I was in LA when Hans called me asking if I would like to be part of a super band for the Oscars. There was Pharrell [Williams], Giorgio Moroder, Junkie XL, Sheila E., Hans and I. So we hung out in his studio, rehearsing, and he was very generous and encouraging. ‘I have done only half the movies you have done, buddy,’ he said.

He uses Cubase (a music production software, developed by Steinberg) and I use Logic (developed by Apple). He can tell [Steinberg] to modify the software. He got that power. I don’t have that much influence. I can’t tell Apple, ‘Can you change this for me?’ We talked about these things.

Q/ You have had a long-standing relationship with director Subhash Ghai, with whom you collaborated for Taal 25 years ago.

A/ Yes, he is my Hindi and Punjabi teacher. Even when I had success with Rangeela, Roja and Bombay, I felt the core Hindi audience at the time belonged to people like Ghai. Everyone who would meet me would say, ‘You know, you should work with Subhash Ghai.’ And I didn’t even know who the man was.

So, one night, as I was sleeping, the fax machine started buzzing. ‘I am Subhash Ghai, and I’d love to meet you,’ said the message. I was thrilled. I went and met him in a couple of days, and the movie we started working on, called Shikhar, never actually took off. The main track of Taal, ‘Ishq Bina’, was actually composed for that film. We still have four or five songs left from that movie―all of which he has still got. With Taal, my concern was the music was primarily rhythmic. So I worked with Bakshi sahab (lyricist Anand Bakshi) to focus on meaningful lyrics, ensuring that the melodies were grounded.

Ghai is a great fan of music and respects the process. He came to Chennai to be among us while we worked; he could have been in Bombay, where everyone would wait for him. Down south, we don’t like people pushing Hindi on us, but I respect all languages, and I took to it well.

Q/ Earlier, producers used to call the shots. But, with the decentralisation and distribution of music through streaming platforms, how are the dynamics changing?

A/ There are good and bad things. Budding composers now have more opportunities. I don’t know whether they are exploited; but at least they are getting exposure, which is good. New singers, songwriters, producers and composers are emerging, which is great.

The problem is that the control over quality and the way people listened to music is no longer there. We used to listen to FM stations and Chitrahaar; now, with so many streams available, we don’t know where the good things are. This is why movie promotions are important―when a movie becomes a hit, its songs act as a sort of curator for listeners. That is one of the reasons I still focus on film music.

Q/ Many composers are fighting for copyright ownership. You have managed to avoid such issues.

A/ I believe in always following certain ethics. You can’t take a song from a movie and use it in another movie six years later, saying you are reimagining it. You can’t reimagine people’s work without their permission. You could post it on Instagram, but certainly not make it mainstream.

An even bigger evil is people misusing AI and not paying the composer even if they are borrowing his style. We need to bell this cat, because it could lead to major ethical issues. People could lose jobs.

In my opinion, AI should be used to tackle challenges that human beings procrastinate on―like [improving] the justice system, infrastructure and education, and empowering the underprivileged.

Q/ You have said often that you are a blend of your parents―musician R.K. Shekhar, who died when you were young, and Kareema Begum, who brought you up and your three siblings.

A/ The memory of my father’s death is intolerably dark, which is why I don’t talk about him. He used to take me to the studios, and after his death, people praised him. There is a clip of [composer] Ilaiyaraaja talking about how he and my father learnt from the same master.

His end was not a good one―his face resembled a skull, his stomach protruded, his legs were bony. But I think his hard work was a blessing for us. My mother was a very strong figure―the resilience she showed as she raised all four of us is what I have learnt from her.

Q/ Are there new artistes whose work you admire?

A/ All those whom I follow on social media. But the one song I have been listening to on loop is something I saw in Leeds―[the opera] Orpheus. There is a gentleman who has composed beautifully―a Sri Lankan artiste was singing that on stage. Outside of work, I don’t listen to music―just like a chef doesn’t want to cook after hours.

Q/ How do you handle the pressure to not repeat yourself?

A/ I take on less work now. In the past, music directors would work on 40 movies a year, almost like a factory, but I believe that can take away the joy of the process and lead to monotony. I have done a lot of movies, so I am planning to relax a bit and focus on a few major projects and some personal ventures, like Secret Mountain.

Q/ Is there a director who both inspires you and is difficult to work with?

A/ Mani Ratnam! (Laughs.) I think the more trust you have in someone, the more you torture yourself. Some directors are very clear about what they want, so the projects move faster. But Mani Ratnam will say, ‘Give me something,’ and you wonder and torture yourself to give him something inspiring. Meanwhile, he quietly enjoys it… in a good way of course.

Q/ Is there a song that you think was released at the wrong time?

A/ 99 Songs. It was lockdown, and I just wanted to get on with my life. So, after a while, [working on it] became a torment, and [the film] inevitably suffered. I just moved on.

Q/ How does it feel to know that you are a global icon?

A/ I don’t really know! My focus now is on how to create Broadway-style productions in Chennai, and what it would take to get the right infrastructure and investment for that. I am starting to think more like an entrepreneur than just a musician. I want to give back to the society now; I want to inspire generations.

Q/ How do you control your mind?

A/ I have trained myself to be in a Zen state―neither happy, nor sad; neither fully fed, nor hungry; neither sleepy, nor fully awake. That is the best state for making music―you don’t exist, only the art exists. When you go deep into philosophy, you realise that there is life and there is death, and we are in between. So, don’t take anything seriously.