MULTIPLE THRUSTER

MALFUNCTIONS. Helium leaks. In the context of a space mission, all that sounds rather alarming. But, not for experienced astronauts. American astronauts Sunita Williams and Barry ‘Butch’ Wilmore arrived at the International Space Station (ISS) in June after “managing” such issues. The two former Navy officers recently completed six months in space on a mission originally intended to be for a week, after their capsule was deemed unsafe to return them to earth. The duo’s return is now scheduled for February 2025. Eight months of extended stay in space (NASA does not like ‘stranded’ or ‘stuck’), even with enough supplies, may seem like an unwelcome prospect for the uninitiated, but astronauts, evidently, are built different.

“Living in space is super fun,” Williams told students from the Sunita L Williams Elementary School in Needham, Massachusetts―her hometown―on December 4. Her mission partner sees it as just being on “a different path”.

As NASA administrator Bill Nelson put it in the wake of the duo’s extended stay: “Space flight is risky, even at its safest and even at its most routine, and a test flight by nature is neither safe nor routine.”

That is precisely why the making of an astronaut is so crucial.

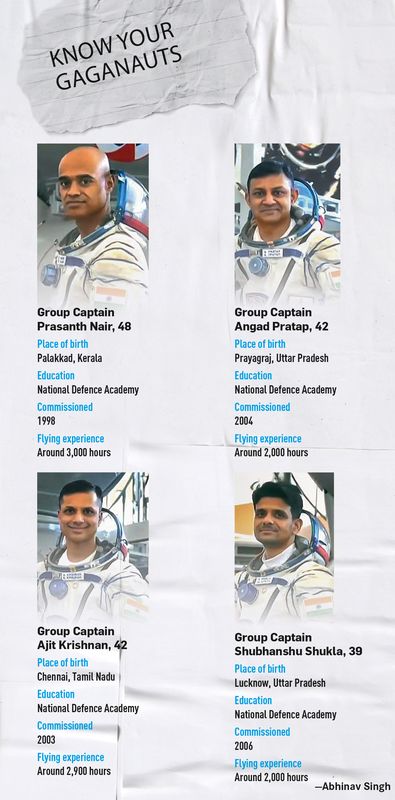

February 27, 2024, was a momentous day for India. On that day, the four gaganauts training for the Indian Space Research Organisation’s Rs20,000-crore Gaganyaan programme were introduced to the nation by Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Group Captains Prasanth Nair, Ajit Krishnan, Angad Pratap and Wing Commander Shubhanshu Shukla (now group captain)―test pilots of the Indian Air Force―were given “astronaut wings” by the prime minister. They have finished preparatory training at the Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Centre in Russia, the facility where India’s first space traveller, Rakesh Sharma, prepared for his 1984 voyage.

The centre, located in Star City, approximately 30km north of Moscow, is named after Yuri Gagarin, the first person to journey to space, and has state-of-the-art technology, including comprehensive simulators. It provides extensive survival training for a variety of potential landing scenarios, such as mountains, forests, marshes, deserts, arctic and maritime. The gaganauts have completed 13 months of intensive training at the centre and multiple stages of theoretical and physical preparations in India, which included over 200 lectures on engineering topics related to space flight. They have also completed 39 weeks of intensive crew training activity and have participated in test missions. ISRO is now pursuing a joint mission to the ISS with NASA and US private firm Axiom Space, with at least one of the four gaganauts-in-training expected to be part of the voyage (Shukla has been designated “prime astronaut” for the mission).

Countries that pioneered space exploration select both military personnel and civilians for space missions. India has picked IAF test pilots to be gaganauts, and it is easy to see why. They are well-suited to the demands of the training, being both physiologically and psychologically attuned to functioning under extreme scenarios. They have experience flying different types of aircraft and acquaint themselves with new systems quickly.

The health tests which were part of the selection process included thorough cardiovascular assessments, vision tests requiring 20/20 results (correctable with glasses), hearing tests and neurological evaluations. The ability to cope with prolonged isolation and stress was gauged through psychological assessments. The entire process included multiple stages of screening and several rounds of interviews with expert panels.

The initial training of astronauts focuses on understanding space systems, spacecraft operations, orbital mechanics and mission planning. This foundational knowledge is crucial for the successful execution of space missions. Training in robotics includes the use of robotic arms and other automated systems on the spacecraft, which are essential for various tasks such as docking and repairs. Medical training is provided to ensure astronauts can handle emergencies, perform CPR, tend to wounds, and utilise on-board medical equipment.

Advanced training involves extravehicular activity (EVA) training, where astronauts learn to spacewalk, use EVA suits and tools, and perform repairs and maintenance outside the spacecraft. They also receive training to conduct and manage scientific research in microgravity, covering a wide range of experiments in biology, physics, and materials science. Survival training, apart from diverse landing environments, involves physical endurance, navigation skills and tactics.

A critical part of the training is simulation, which uses microgravity simulators like parabolic flights and neutral buoyancy pools, and high-fidelity simulators that replicate conditions for practising launch, docking, re-entry and emergency procedures.

As India continues its preparations for Gaganyaan, which has been expanded to include eight missions―four by 2026 and the remaining by 2028―THE WEEK spoke to a NASA astronaut and a Russian cosmonaut for an in-depth understanding of the training of space travellers and their experiences on missions.

“THE FOOD WAS QUITE NICE”

Nicole Stott has two space flights and 104 days in space under her belt, as a crew member on both the ISS and NASA’s retired Space Shuttle programme. She was the tenth woman to spacewalk, the first to operate the ISS robotic arm to capture a free-flying cargo vehicle and the first to paint with watercolours in space.

Before her selection in 2000, Stott was an engineer in the Space Shuttle programme for more than a decade. One of 17 astronaut candidates chosen out of 9,000 applicants, Stott remembers the process clearly, including her final interview. “The aim [of the interview] is to know you as a person and why you want to go to space for an extended period,” she told THE WEEK. “If things go wrong, how are you going to react, how will you be as a crew mate to the rest of the crew.”

Her training included flying in T-38 jets, simulation and learning to spacewalk, the operation of robotic arms, getting used to space food and living in Aquarius, an undersea research station (off the coast of Florida) for 18 days. She said Aquarius was the experience closest to living and working in space. “I am a recreational scuba diver and was used to such an experience,” she said. “The Aquarius experience was aimed to take a trainee out of the comfort zone and to understand how to work better to solve problems. It is about the size of a big school bus and sits on the sea floor [at a depth of about] 65 feet.” She said that while the lab had normal oxygen flow, those inside cannot go out without donning special suits. “It is an extreme environment and one cannot swim to the surface to escape it, because, once you are down there for an hour, your body is saturated by nitrogen and you might kill yourself if you attempt to swim.”

All through her training, Stott knew she may not get to fly at all―there are times when a trained astronaut may not go on an actual mission. She had to wait nine years before her maiden space flight in 2009. Stott recalls her feelings at the time of that thrilling first flight. “I was not afraid, but I thought about my family,” she said. “My son was seven when I flew for the first time. I knew that everything will be fine. I got to talk to them as soon as I got to space. But, it is still difficult [not to think of family] as you strap into a rocket. Once you are strapped in, you go from zero to 17,500 miles an hour, and, very quickly... it takes about eight and a half minutes to get to space.” She says the simulation does a good job of replicating the experience in space.

Stott is all praise for space food. “At the space station, the food was quite nice and we had variety,” she said. “It is like camping food; most of it has the water sucked out of it, or like military rations and ready to eat. There are no big refrigerators, but, at the space station, it is easy to resupply from the ground.”

At the fully solar-powered ISS, there is a daily work schedule, which, Stott says, is similar to how things are on earth. There is a two-hour exercise schedule to maintain bone and heart health and planned meals throughout the day. There is also an eight-hour sleep schedule. “I used to sleep comfortably in my individual crew compartment―it is the size of an old phone booth. It is cool, dark and has nice air flow.”

The schedule for each astronaut is decided by the ground station. The tasks include conducting experiments as directed by scientists on earth and maintenance work, which sometimes necessitates spacewalks. Stott’s “incredible” experience of spacewalking left her wanting more. “I wish I could have done another one,” she said. “You get a whole different view of the earth and the sun. One needs to ensure that one is hooked to the space station and not going to float away. We are trained to do that and there is a jet pack and we are trained to fly back in case we lose control.”

She said the ISS had all the required medical equipment to take care of any medical emergency on board. “We also check the health of our fellow crew mates,” she said. The astronauts always have the option of talking to doctors on the ground.

Interestingly, the supplies from earth rarely includes fresh water, which is generated on board, from recycled urine, sweat and condensation.

Stott said the most complicated aspect of crewed space missions is re-entry. Kalpana Chawla and her fellow astronauts had died in 2003 when the Space Shuttle Columbia disintegrated as it re-entered the atmosphere. “She was one of the humblest human beings I had ever been blessed to meet and I am very grateful to have known her; very sad that she is not among us any more,” said Stott. Elaborating on re-entry, she said that the process is respectful, deliberate and diligent. “Falling from space back to the earth’s atmosphere is a pretty extreme thing,” she said. “The heat, the dynamics of it, the precision is just amazing.”

“I WAS OVERWHELMED WITH JOY”

Cosmonaut Sergei Nikolayevich Revin served as a crew member on board the ISS in 2012. The Russian spent 124 days, 23 hours and 52 minutes at the ISS. Revin is not fluent in English, so his interaction with THE WEEK and translation was coordinated by Natalina Litvinova, president, the Global Union of Genesis, Russia.

Like Stott, Revin, too, was an engineer before he was selected to be a cosmonaut. He said his training programme was fascinating and that he took multiple tests, both in Russia and in other countries, and also studied different training modules and systems. “We had many workouts and regular flights, during which aerobatics were done,” he told THE WEEK. “We also lived in harsh environments, such as the desert and the tundra. It was difficult, but very exciting and interesting.”

Also Read

- Why human-rated LVM3 will be crucial for Gaganyaan mission

- From space sickness to increased risk of cancer, navigating the challenges of prolonged stay in space

- Explained: The challenging task of entering the earth’s atmosphere from orbit

- Menu for Gaganauts: The progress and processes in the domain of space food offer some familiar

Revin highlighted the importance of nutrition and detailed the steps that went into ensuring that the cosmonauts were comfortable with the food they would have to eat in space. “We had preliminary tasting of dishes,” he said. “We had a 10-point scale and indicated our preferences and this was taken into account when preparing the menu for the flight period. Usually, these are various freeze-dried products and canned food. We also consumed lots of milk, cottage cheese, and cheeses.”

He praised the simulation and training protocols at the Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Centre and at the various foreign training centres. “The conditions are as close as possible to real conditions,” he said. “The main aspect is to work with on-board systems and also work in zero gravity.”

By the time space travellers get to the ISS, they have undergone so much training that life on board the ISS is “almost routine”, to use Revin’s words―wake up at 7am, exercise, eat, work and lights out at 11pm (the ISS observes Greenwich Mean Time). But, the flight to space, he said, is an experience to cherish for a lifetime. “Literally in nine minutes, I was in space,” he said. “The work at the ISS was interesting and we had an important responsibility, but it was during the flight that I was overwhelmed with joy. The earth is beautiful.”