Machoi Glacier, Drass, Zojila, Sonamarg & Gulmarg

Rafique Ahmad Malik, 47, sits beneath the Himalayan peaks, not far from crevasses where blood stains have been washed away by melting snow. He is battle-ready, having sensed his adversary in the icy winds blowing across the northern frontier, home to the world’s toughest and highest borders. The Himalayan range separates India from Pakistan in the northwest and China in the north. Mountain combat here is arduous, as the terrain favours small defensive forces holding key passes and valleys, where natural obstacles provide critical support. A seasoned mountaineer is a skilled warrior. Such individuals listen to the wind, identify rocks, follow trails and often uncover secrets hidden in the mountains to surprise the enemy.

It was at these perilous heights that Everester Narendra “Bull” Kumar won Siachen for India 40 years ago. Colonel Kumar, heading the Mountain Warfare School in Gulmarg in 1977, met a German rafter during an expedition in the Nubra valley. The rafter revealed that Pakistan had been issuing climbing licences for the area and showed Kumar a US-printed map of northern Kashmir marking Siachen, the world’s largest glacier, as part of Pakistan-held territory. Kumar reported this to the Army’s operations chief, Lieutenant General M.L. Chibber. Soon after, General T.N. Raina, chief of the Army staff, authorised a “training trek” for Kumar and his team to Siachen. They returned with damning evidence―tin cans and cigarette packs left by Pakistani climbers. Kumar and his team reconnoitred several peaks―Pir Panjal, Himalayas, Zanskar, Ladakh, Saltoro, Karakoram and Agil―gathering intelligence on Pakistan’s plans to occupy Indian territory. The account of these treks played a vital role in Operation Meghdoot in 1984, when Indian forces climbed the glacier to secure it. The main base was named “Kumar” in his honour. Wars fought in the mountains hinge on who dominates the peaks.

Today, at the High Altitude Warfare School (HAWS) in Gulmarg, Rafique and the ‘White Devils’ are preparing for future wars, which are expected to be swift, precise and driven by technology and intelligence. The trainees at HAWS are called White Devils, and are trained at the Machoi Glacier across Zojila in Ladakh’s Drass region. Here, they learn ice and snow craft under inclement weather and sub-zero temperatures. High-end weapons, lightweight mountain gear, advanced techniques, surveillance capabilities and rapid mobility make them a formidable force.

Born in a humble farming family in Anantnag, Rafique grew up in the mountains and, like any highlander, fell quickly in love with the peaks. However, the distant sounds of gunfire, classmates lost in encounters and militants crossing peaks under the cover of darkness shattered the idyll. As a teenager, Rafique often ran to the mountains, restless until he reached the summit. It became a habit as militancy surged in Jammu and Kashmir during the 1980s and 1990s. “I used to run like a leopard. I asked around my village about a vocation that would match my skills. They suggested the Army,” said Rafique.

In 1995, Rafique joined an infantry battalion but soon realised that his duties took him away from the mountains. “I was perplexed. The reason I joined the Army was to be close to the mountains. I inquired about how I could return to them and was told about HAWS, where I could train to become a mountain warrior.”

Rafique’s unwavering focus brought him to HAWS, where his trainers noticed his unique gait, speed and observational skills, and started sending him on expeditions. In 2011, he scaled Mount Manaslu, the world’s eighth highest peak, becoming the first Indian to do so since 1985.

“Like any mountaineer, it was my dream to climb Mount Everest,” says Rafique. But such dreams were unheard of in Jammu and Kashmir. After receiving facilities, including skis and mountain gear, I began training at HAWS.” Rafique’s two years of preparation were relentless―he refused to take leave despite being newly married. His family was unaware of his plans, and his village began worrying about his long absence. Elders speculated whether the mountains had lured him to the other side, where indoctrination, money and terror recruiters were waiting.

Rafique, however, was busy travelling to Delhi, climbing the Siachen Glacier, and training in Kathmandu and Switzerland. From almost 250 soldiers, he made it to the final six selected for an Everest expedition. In 2014, Rafique became the first Kashmiri to scale Mount Everest, a record that remains unbroken. His skills in outmanoeuvring the enemy are as honed as his ability to capture peaks. A subedar major in the Army, Rafique has received eight commendation cards (awards for acts of gallantry or distinguished service) from the Army chief.

“The techniques we learn in mountaineering and snowcraft give us endurance and the skills to operate in the toughest terrains,” said Rafique. “Early in my career, I fell into a crevasse during an expedition, severely injuring my fingers. But I stitched them up and returned to climbing.”

Rafique’s journey reflects the story of many White Devils, who are constantly mastering new skills at dangerous heights near the two ‘Lines of Control’. They have fought intense battles, defeating Pakistan in Kargil in 1999 and helping the Army dominate heights during the 2020 clashes with Chinese soldiers in Ladakh’s Galwan valley.

The lessons began with the 1947-48 conflict with Pakistan, where Indian soldiers faced challenges due to a lack of high-mobility equipment and technology, restricting operations in the mountains. One day, General K.S. Thimayya (who later on became Army chief from 1957 to 1961) visited the Ski Club of India in Gulmarg and found 100 pairs of skis left behind by the British. Thimayya asked the club to give the skis to the Army to help train soldiers. Thus, HAWS was born on December 11, 1948, with its first instructors coming from the Ski Club. HAWS initially operated as the 19th Infantry Division Ski School and came to be known as the Winter Warfare School. It was renamed HAWS in 1962. In 1993, it began functioning under the Army Training Command.

During Operation Vijay in 1999, nine teams that trained at HAWS played a key role in successfully recapturing large parts of Indian territory from Pakistan. “The Kargil war didn’t teach us the importance of mountain warfare, we already knew that. What Kargil did was present new operational challenges, which we incorporated into our training,” said Major General Bruce Fernandez, commandant of HAWS. “A country’s geography remains unchanged, and the Himalayas will always be there. To suggest that mountain warfare will become irrelevant is short-sighted. We will never stop preparing for war in the mountains.”

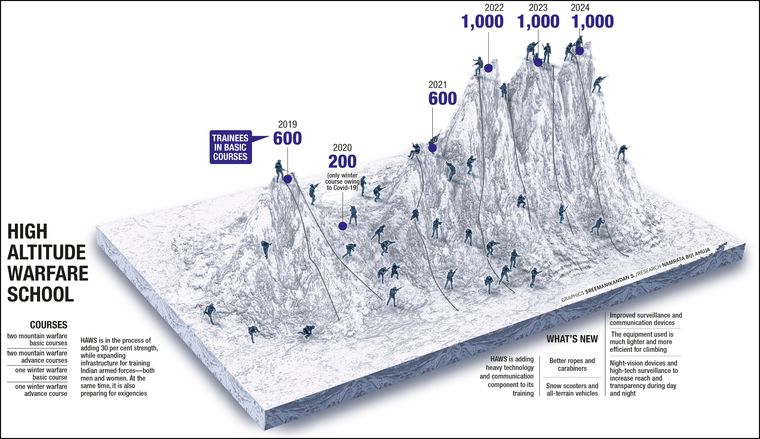

This is why HAWS is increasing its training capacity. It has doubled the number of soldiers it is training in the past few years and is in the process of adding another 30 per cent to its strength while expanding infrastructure to train various arms of the Indian armed forces, both men and women. At the same time, it is also preparing for exigencies.

“Today’s wars involve operating in smaller groups due to the high transparency and visibility afforded by technology, such as satellites, radars and computer systems,” said Fernandes. “As a result, we are focusing on empowering junior leadership to also act as decision-makers at the tactical level, as they will more often than not find themselves in situations where they must decide and act.” This approach enables the armed forces to operate with greater independence and adaptability in a highly visible environment, he added.

Warfare evolves with time, greatly influenced by technology and the geostrategic positioning of nations. Whether it is the recent shift of theatre by Pakistan-based terrorist groups from the Kashmir valley to the high-altitude jungles of Jammu or deployment along the Line of Actual Control, the Indian armed forces’ training efforts continue relentlessly.

HAWS trains the Army at three different locations: winter warfare at Gulmarg, mountain warfare at Sonmarg, and ice craft at Machoi Glacier. The Machoi Glacier lies between Gumri and Matayen, a rare stretch that has seen two wars. Gumri, a small valley surrounded by sharp peaks, has memories of the 1947 Indo-Pak war and the 1999 Kargil war. In Gumri, General Thimayya decided to surprise the enemy and moved up tanks across Zojila to clear Drass and Kargil. Almost 50 years later, Gumri was the staging area for all inducting troops into the war and Matayen was used as one of the gun positions. It is here that THE WEEK spent time with the mountain warriors as they moved from one perilously narrow and jagged terrain to the next.

The basic tactical exercises―rock climbing, route opening, stream crossing, rappelling and survival in the mountains―begin in May and last seven weeks. These are followed by an advanced course lasting four weeks. “The evaluation of the basic course paves the way for a select few to join the advanced course, which includes one week of advanced ice craft, attack by infiltration, long-range patrols, advanced climbing techniques and mountaineering expeditions,” said Lieutenant Colonel Manish Dhayani, senior instructor at HAWS. Before the mountain warfare series begins, the instructors undergo a refresher course, where their skills are rigorously tested. For every four trainees, there is one instructor.

This time, the teams are preparing for an expedition for “height gain” as they get ready to scale two peaks. This includes establishing a base camp on a glacier before attempting the summits. The expedition starts well past midnight, when the snow is hard, and the mountain terrain is almost invisible. “The element of fear is lost in the darkness because you cannot assess the danger levels. The training is better,” said Dhayani. “For those coming from peace locations, it is an uphill task, especially when you have to use your forelimbs.” In 2009, when Dhayani was training at HAWS, he was caught in an avalanche. “That day, somehow, I skipped the tea break and joined my jawan in a tree pit to share a biscuit,” he said. When the avalanche struck, he recalled the swimming action taught by the instructors, which saved him from being buried under the snow. Although the platoon lost one member, Dhayani and his jawan were saved.

At Machoi Glacier, there are jubilant faces, laughter and songs at sunset as soldiers huddle together after days of negotiating the mountains. Rappelling down cliffs with rifles, their sweat and smiles have become part of the snow.

The White Devils have made the unwelcoming terrains skiable. From traditional methods using herringbone techniques to smoothen the snow, snow groomers and snow scooters now save time and energy, allowing more time to practise newer techniques.

When Luxmi Kant, 43, a naib subedar in the Special Forces, mastered these techniques, little did he know he would use them during a live terrorist operation to retrieve the fallen brothers. In a counter-terrorist operation in the higher reaches surrounding Kashmir valley, some personnel of another battalion suffered fatal casualties. As the gunfire ceased, the cliffs bore silent witness to the bravery of the martyred soldiers. Luxmi Kant received orders to retrieve the bodies even as operations against the terrorists continued. Having aced the same cliffs and terrain during a previous posting, he quickly made a mental map.

“It was the first time I was negotiating the mountains while terrorists were still looking for an opportunity to strike. Since I knew the area well and was adept at mountain warfare skills, we climbed the peak at dawn and rappelled down 40m between two cliffs to wrap the bodies and bring them home.” During the operation, the bodies of two terrorists were also recovered. “The terrorists have no rules. But we must save our men and bring them home, following the command of our forces,” he said.

As the day darkened and temperatures plummeted, the music faded away into the ranges. Soldiers walked on the line, preparing for daring expeditions, rescuing their brothers from the brink of death and readying themselves for future wars.

In June 2024, Fernandez led a gruelling expedition to retrieve the bodies of three havildar instructors trapped under avalanche debris. In July 2023, a HAWS mountaineering expedition set out to scale Mount Kun in Ladakh. Four team members fell into a crevasse and were buried under a massive volume of snow in October. The bodies of Havildar Rohit Kumar, Havildar Thakur Bahadur Ale and Naik Gautam Rajbanshi were trapped deep within a crevasse covered by layers of ice. The body of Lance Naik Stanzin Targais was recovered soon after the accident.

HAWS launched Operation RTG (Rohit, Thakur, Gautam) to retrieve the missing bodies. Fernandez stationed himself at the roadhead camp to oversee the operation until the mortal remains were transported to their families with full military honours. “Our ethos is never to leave our fallen behind,” he said. “What is equally satisfying is that it brought closure to the families.”

The heroes of HAWS are future-ready. Captain Bharti Rao from the 66 Engineer Regiment is the first woman trainee at HAWS. Reflecting changing times, as women take on various support roles in the field, Bharti’s presence at Machoi signifies more than gender parity in the armed forces. The 29-year-old helps fill critical gaps in the Army’s essential components, with engineers, signals and other arms working alongside infantry as force multipliers during operations.

A civil engineer from Bhopal, Bharti left a lucrative job in Delhi to brave wind, ice and snow. “I wanted to be part of the pioneer course. I told myself that if I am going to be the first woman in the mountaineering course, I must achieve something new. During the Kargil war, we were attacked from unexpected and unconventional areas. So it is a mix of technical and tactical training. Today, I am learning rock craft, snow craft and navigation,” she said. “Every day, you learn to walk on a glacier. Who else gets this opportunity?” As an engineer officer, Bharti’s combat role aligns closely with the infantry. She moves with the troops, enabling their swift movement while simultaneously restricting enemy movement. The art of warfare has made her a stealthy warrior who understands that wars in this sector will be fought at altitudes of no less than 17,000 feet. She ensures her inventory and supplies move steadily alongside.

And how does she deter the enemy? “It all depends on what sort of explosives I need, what sort of stabilisation I require, and how my wares would be deployed,” said Bharti. She highlights the advantage of joining the Army at a young age and training at HAWS as an engineer officer, which opens up numerous opportunities for the future. “I am already part of a combat support arm. Who knows, maybe tomorrow I will be able to lead a team into battle.”

These days, soldiers at HAWS employ new communication techniques. “The role of technology and communication was not as critical in the past as it is today. Now, we must fight using all the skills at our disposal for better cohesion in the mountains,” said a Signals officer. The Corps of Signals provides communication support specifically tailored to the needs of the troops. “When it comes to communication, we are very well trained and equipped. With the use of satellites, communication has evolved in multiple ways.”

The only other time the mountain warriors encounter another female officer atop the glacier is when they enter the medical tent and are greeted by Captain Durga Mohan. “I’m very fortunate to be here, as very few people are posted here so early in their career,” said the medical professional from Thrissur, Kerala.

Popularly known as Rani Lakshmi Bai in the Himalayas, Captain Durga’s journey serves as an inspiration to the warriors. “When I first climbed the glacier, I felt this wasn’t my cup of tea,” she said. But over time, the mountains grew on her. More importantly, attending to the soldiers and officers became second nature, as she witnessed them battling mental challenges daily.

“Being away from their families in such harsh living conditions is a test of both mental and physical endurance. It is the brotherhood that keeps them going,” said Captain Durga.

HAWS is a place where legends live, frozen in time. Subedar Major Arjun Thapa, a third-generation soldier from Nepal, holds the distinction of completing a polar expedition. His skills are honed not only in the icy Himalayan peaks, but also at the South Pole, which was possibly his first trip outside the country.

“I was sent to Greenland for 28 days of training. I still remember the long flight with multiple layovers,” he recalls with a smile. However, what does not seem like a long journey to him is his trek to the South Pole―a post-to-pole journey covering 1,170km in Antarctica. There, wind chills, dazzling sun, sleepless nights, and packed food were his companions in one of the toughest human endurance tests. “Navigation is challenging. It is difficult to pull the sledge through snow dunes, and the high winds don’t let you sleep,” he said.

Legends like Thapa are invaluable assets to the Army, as they not only inspire young warriors but also carry with them a wealth of knowledge that can be crucial in critical moments. Thapa has travelled from the Karakoram to Lipulekh, crossing 26 mountain passes along the Line of Actual Control, gaining an intimate understanding of the terrain on both sides. “Border infrastructure is the need of the hour, and it’s a positive sign that we are focusing on border roads, improved connectivity, and enhanced strategies to safeguard our interests in border areas,” he said.

Also Read

- 'HAWS is focusing on empowering junior leadership': Major General Bruce Fernandez

- 'India has advantage in high altitude combat': Lieutenant General S.L. Narasimhan (retd)

- How mountaineering expeditions play crucial role in mountain warfare training

- 'India is preparing for a two-and-a-half-front war': Radha Krishna Mathur

Over the years, the Himalayas have been a training ground for warriors from across the globe. Soldiers from Nordic countries and Africa have brought their unique experiences to these peaks. Lieutenant Malakia Kashava from Namibia can’t help but compare the relatively easy mountainous treks back home. “India has an advantage, as its natural features provide countless opportunities for training armed forces,” he said. His Ugandan counterpart agreed. “Our enemy operates in the mountains along the border with Congo. The training here will enhance our operational capabilities as we learn advanced techniques,” said Kaihura Jowel.

The Indian military’s greatest advantage lies in its distinct upper hand over other militaries, having fought and won multiple wars, some decisively. This has allowed military planners to battle-test their doctrines and strategies repeatedly. Additionally, advances in signals and electronic warfare have become critical components of communication strategies in the mountains.

However, military strategists at HAWS caution against relying solely on technology. No amount of drones, rockets or information warfare can secure victory unless soldiers physically climb the mountains and capture the peaks. Similarly, unconventional methods of warfare remain indispensable for defending territories. The famous cliff assault during the Kargil War of 1999 is one such example. Now, 25 years later, HAWS continues to prepare mountain warriors for even greater challenges in the Himalayas.