On the third floor in a ward at the trauma centre of Lucknow’s King George Medical University (KGMU), hope lives and dies more poignantly than it does on any of the other floors.

It is here, in the rise and fall of breaths supported by ventilators, that a nation is making a cautious check of the health of its justice system while also taking notes on the many malaises of its political structure. Here lies a gang rape survivor and her lawyer Mahendra Singh, grievously injured for taking on four-time MLA Kuldeep Singh Sengar, now in jail, and his associates for a crime they committed in 2017.

The survivor's aunts and her staunchest allies, sisters Pushpa and Sheela Singh, lie in a mortuary not far from the trauma centre. Pushpa’s husband, Mahesh Singh, who has steered the survivor’s search for justice, is in a jail in Rae Bareli—convicted for attempt to murder—since February 2019.

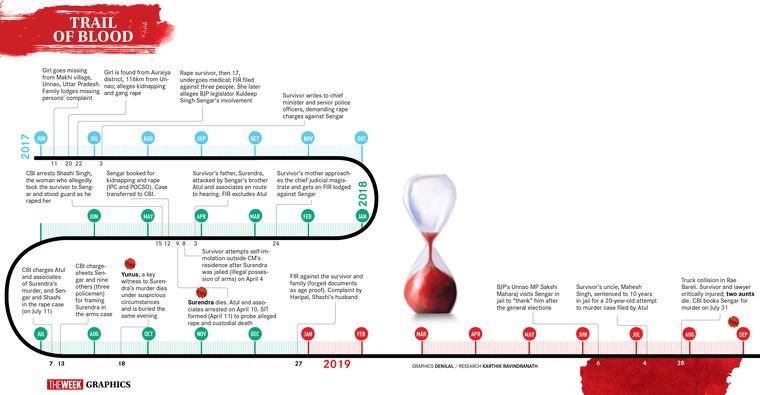

On July 28, the survivor and her aunts got into Mahendra’s car to undertake a 98km journey to meet Mahesh. The survivor, who now lives in Delhi, had come to her village—Makhi—the preceding week. There were three guards assigned to be with her in Delhi, and seven others who guarded her family home in Makhi. But there was none with her on the July 28 trip. The police say the survivor specifically told the guards to not accompany them as there was no space in the car. The survivor’s mother, however, denies it.

At the Pore Dauli crossing, some 20km from the Rae Bareli jail, a truck, with a blackened number plate, rammed into Mahendra's white car. The truck came from the wrong side of the road, said eyewitnesses, and dragged the car for about 100m before halting. There was a light drizzle. The driver and the cleaner fled. After a quick check at Rae Bareli’s district hospital, the car’s occupants were referred to KGMU. Pushpa and Sheela died in a couple of hours.

The survivor’s family has since accused Sengar, who belongs to the state’s ruling BJP, of orchestrating the accident. An FIR filed by Mahesh states, “The MLA would call from one Simple Mishra’s number and my family would be forced to speak to him. If you want to live, change your statement [he would threaten]. This used to happen in front of the police stationed at our home.” Sengar, his brother Manoj and eight others are named in the FIR; the case has been handed over to the CBI now. Another 15 to 20 unnamed people are accused of forcing the family to compromise or risk being killed.

The compromise the MLA and his aides have been seeking is over the case filed by the survivor, who charged them with raping her after kidnapping her in June 2017. The survivor was then 17, says her mother. Initially, a case of kidnapping and rape was filed against three people; the charge against Sengar took some time to come. In the immediate aftermath of the ordeal, the survivor had fallen silent. Her family shifted her to Mahesh’s home in Delhi, which is where she first told Pushpa about Sengar's involvement. Multiple attempts to file a FIR against the MLA were unsuccessful. Then his henchmen thrashed the girl’s father. Desperate and scared, she tried to immolate herself in front of the residence of Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath. Media frenzy followed and an FIR was filed. A CBI inquiry was initiated and the MLA and the other accused arrested. Security was offered to the girl. Yet the family continued to receive threats. Over the last year, 35 complaints about the threats were made to the local police, who deemed them untrue, says the family.

This July 12, the survivor’s mother, sister and aunt wrote to the Chief Justice of India, with copies marked to the Chief Justice of Allahabad High Court and state principal secretary (home) among others, pleading for directions to the local police to take cognizance of their complaints about the threats. One of the threats mentioned in the one-page letter is attributed to Haripal Singh, husband of Shashi Singh, accused in the kidnapping case. It reads, “We have bought the judge and bailed Shashi.... Compromise or you will all be framed in cases. You will rot in jail.”

Akbal Bahadur Singh, a 72-year-old relative of the survivor, says it was always an unequal battle, made worse by the local police that openly said it would do the MLA’s bidding. Yet, no one expected the family to be wiped out. “Even after the rape case was registered, we had hoped that there could have been some kind of compromise,” he says. “The girl’s life is anyway finished. Who will marry her now? But Sengar could have settled matters amicably—given her money; helped her to marry. Now there is no one left to compromise with. It is all over”.

In a state that has the largest share of crimes against women in the country (14.5 per cent in 2016 as per the National Crime Records Bureau), Akbal’s view that women must take crime in their stride is not unique. But it is not a view held by the survivor. “She did not speak much. But on the few occasions she did, she was clear that she would seek justice,” says Unnao-based lawyer Vimal Kumar Yadav, who was assisting Mahendra in the survivor’s case. “Why did my senior take the case? Who knows why. I never asked. He belonged to the survivor’s village. It was a call beyond professionalism. Sometimes the truth requires sacrifices.”

Since the accident, Vimal has been at the trauma centre playing the role of lawyer, confidant and counsellor to the survivor’s family of three sisters, a brother and a distraught mother. All family members, except for Mahesh's, have stayed away. As have the villagers, says Vimal.

“He is a big, powerful man. A jail cannot hold him. No one in the village dared to oppose him,” says the survivor's elder sister. “We have been on our own. They killed all those who could speak. They might even kill us. But now, what is there to lose? Why must we stop fighting?” Her brother, just five, looks on. Mahesh's son, 9, is the family’s oldest surviving male who is free.

In the long months when the family was attempting to file a case against Sengar, no organisation, local or from Lucknow (just 65km away), stepped in to help. But on April 12, 2018, a few days after the survivor's self-immolation attempt, a fact-finding committee of organisations working on the issue of violence against women met the family to piece together the details of her ordeal. “After the kidnapping, the girl did not mention the role of the MLA. She had been scared into silence,” recalls Richa Rastogi, a member of the team. “Only those who kidnapped her were named in the initial report. After she came out of her trauma, she opened up to her aunt. The family was shocked as it had shared close relations with Sengar’s family. There was disbelief about how he could have done this with their daughter.”

Sengar’s rise to power was ironically fuelled by the survivor’s family. Her father, Surendra, and his two brothers, Guddu and Mahesh, were “Sengar’s henchmen”, says lawyer Ajendra Awasthi. “Till 1996, the families were on good terms,” he says. “If Sengar’s will was supreme in the village, it was because of the brothers, who would go to any lengths for him. But when the brothers resisted and developed political ambitions of their own, they fell out.” Many false cases were filed against the brothers, he adds. “Guddu died mysteriously. Surendra was beaten to death. Mahesh was jailed. Had it not been for the survivor, there would have been no threats to Sengar. If she survives, it is definitely his end,” says Awasthi, who had filed a parole plea before the High Court for Mahesh to perform Pushpa's last rites. Mahesh was granted a 24-hour parole on July 31.

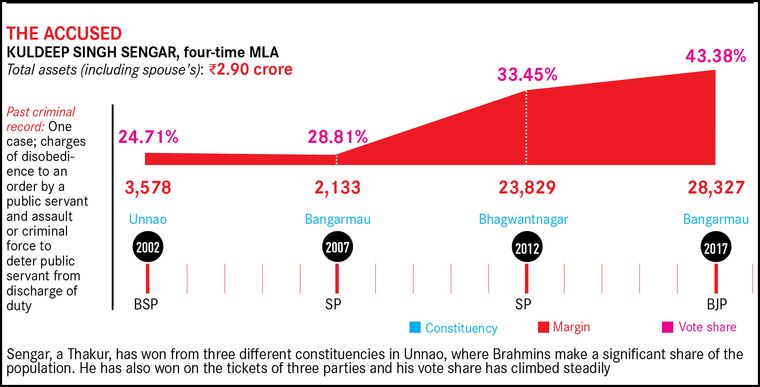

In wealth and power, Awasthi likens Sengar to Raavan, the demon king. Born and bred in Makhi, Sengar inherited the wealth and lands of his maternal grandfather, who had no son of his own. A wily politician, Sengar straddled between parties across the spectrum. He started off as a member of the Youth Congress. In 2002, he became an MLA from Unnao (Sadar) on a Bahujan Samaj Party ticket. In 2007 and 2012, he was elected on a Samajwadi Party ticket from Bangarmau and Bhagwantnagar, respectively. In 2016, he rebelled, and propped his wife, Sangeeta, against the Samajwadi Party candidate in the panchayat polls. In 2017, he joined the BJP, and contested and won from Bangarmau. His long convoy of SUVs was as talked about as his homes spread across acres. One of these homes is just 100m from that of the survivor’s. It was the one she had often visited when the families were on good terms.

“Sengar was a rich man, and known to stand by people in times of need,” says Mradula Asthana, a member of Unnao district’s Juvenile Justice Board. “His popularity steadily grew.” There are others who contend that his influence, though deep, was limited to his village and constituency. It helped that Makhi is dominated by Thakurs, the caste to which Sengar belongs (so does the survivor and the chief minister). This caste dynamic has led to a strange silence in the village where no one wants to be seen taking sides. Sengar’s breakthrough years are believed to have come during his stint with the Samajwadi Party when he profited off illegal sand mining. In the BJP, he is said to have the backing of the powerful Thakur lobby. Action against him thus has been slow.

The All India Democratic Women’s Association is one of the organisations that has stood by the survivor since last April. Madhu Garg, its state president, says, “The victim’s family, especially her uncle Mahesh, is well versed with legal technicalities, as he himself is battling court cases. For long, the rivalry between the families was about upmanship. Sengar rose while the other family struggled to shine politically. Then this girl was caught in the vicious mix of ambition, wealth and power.”

The survivor was also repeatedly failed by the systems that should have brought her justice, including the CBI court hearing the rape case. Since April 2019, CBI court 4 in Lucknow is vacant. There have been three dates since, but in the absence of a judge, the case has not moved. The next date is on August 3. Also, the file for the case is in the safe custody of the CBI court in-charge, who could have transferred it to another court for a speedy hearing.

The case itself is at a perilous stage, where the survivor's age at the time of the crime has been called into question. “The accused has asked for a withdrawal of POCSO [Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act]. We will put forth our arguments when the court is convened again,” says Pawan Bhaskar, one of the lawyers for the survivor.

As per the survivor’s school leaving certificate, she was 17 at the time of the crime. But another certificate from a school in Unnao, which is owned by Sengar's family, shows her to be 19. A forgery case against the survivor is listed in the district court in Unnao.

Meanwhile, scarred by multiple injuries, the exact nature and severity of which is still being judged by the doctors, the survivor and her lawyer fight a lonely battle, one breath at a time.