FOR 40 DAYS, courtroom No 1 in the central wing of the Supreme Court witnessed a fierce legal battle to settle a centuries-old property dispute. Chief Justice of India Ranjan Gogoi, heading a five-judge Constitution bench, heard arguments in the polarising Ayodhya title dispute case, making sure that both the warring sides followed the court’s strict deadlines.

As the hearing drew to a close on October 16, an atmosphere of cautious anticipation descended. The government issued fresh prohibitory orders in Ayodhya, denied leave to officials on “field duty”, and barred television channels from holding live debates from Ayodhya.

“We expect a just judgment from the Supreme Court,” said a statement of the All India Muslim Personal Law Board (AIMPLB). “The case is being watched not only by our nation, but also internationally. It is a test case for the basic values of secularism enshrined in our Constitution.”

Surendra Jain, joint general secretary of the Vishva Hindu Parishad, said all evidence in the case pointed in one direction. “There existed a temple,” it said. “It is time to correct the historical wrong. A grand temple will be built in Ayodhya.”

For the Constitution bench—which includes, apart from Gogoi, Justices S.A. Bobde, D.Y. Chandrachud, Ashok Bhushan and S.A. Nazeer—the task is cut out. It will have to deliver its verdict on the vexed issue before November 17, the day on which Gogoi will retire. Issues of faith, historical evidence and, probably, political expediency will figure in the judges’ minds as they prepare to deliver the verdict.

The judgment is likely to be a landmark one, as it could set a precedent for cases in which faith plays an important role. It could also open the floodgates for similar disputes across the country.

More importantly, the verdict will have wide political ramifications. A judgment favourable to the construction of a Ram temple in Ayodhya will send BJP and Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s stock soaring. If the statue of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel was intended to counter Nehruvian ideals, a grand Ram temple will help the BJP iconise its hindutva politics.

“The reawakening of India and the construction of the Ram temple at the janmasthan (birth place) are important milestones in the hindutva movement, as they give expression to a national cultural requirement,” said Sunil Ambekar, senior RSS pracharak and author of The RSS: Roadmaps for the 21st Century.

The Muslim side has agreed to accept the judgment, apparently because there is schism within the community over continuing with the case. Shia Muslims and a few intellectuals have been advocating that the Muslim side renounce its claim over the disputed land for the sake of peace and harmony.

Even on the last day of the hearing, there were reports that the Sunni Waqf Board, one of the petitioners in the case, would file an affidavit seeking an out-of-court settlement. But, apparently, the petitioners could not reach a consensus. The AIMPLB had earlier said that the status of the disputed land could not be altered in any manner, as the shariah did not permit it.

“No Muslim can surrender or transfer such wakf land,” the board said. “This submission is based on historical facts and evidence that the Babri Masjid was constructed without demolishing a mandir or any other place of worship.”

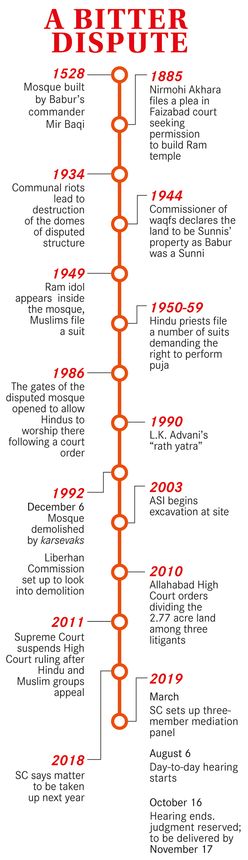

In the case heard by the Constitution bench, Lord Ram himself is a litigant and juristic entity, along with the Nirmohi Akhara, which claims jurisdiction over 2.77 acres of Ram janmasthan. Both of them are respondents, while the Sunni Waqf Board is the main petitioner on the Muslim side. The Constitution bench heard 14 appeals to the 2010 Allahabad High Court verdict, which had ordered that the disputed land be divided among the three main litigants. None of the three had accepted the verdict.

Faith has always been a sensitive issue in India. The Supreme Court has, in recent times, taken a view that constitutional morality takes precedence over issues of faith. Last year, it ruled that women of all ages could enter Sabarimala temple in Kerala—a decision that resulted in widespread protests. In August this year, it ordered the demolition of the Ravidas temple in Delhi, saying it was built on forest land.

The Supreme Court had, in 1994, rejected a presidential reference after the government took control of the disputed land in Ayodhya. It said the executive cannot expect the judiciary to resolve political matters.

The case before the Constitution bench has been marked by acerbic exchanges between lawyers and terse observations by judges. Arguing against the Allahabad High Court judgment, the lawyers representing Lord Ram argued that the birthplace itself was worshipped as a deity and, hence, could not be divided. Senior lawyer K. Parasaran said Babur, the Mughal emperor who is said to have built the mosque in Ayodhya, was a foreigner who came to conquer India. “For Hindus, it (the disputed site) is a birthplace. For Muslims, it is a historical mosque. For Muslims, all mosques are equal,” he said.

Senior advocate Rajeev Dhavan, representing the Sunni Waqf Board, denied the contention that there was no mention of the mosque in the writings of foreign travellers who visited India before Babur’s time. He said travellers were just storytellers and their accounts could not be relied upon. When lawyers representing the Hindu side argued that no prayers were being offered at the mosque before its demolition in 1992, Dhavan said people had been offering namaz.

The matter of prayers in the mosque has legal significance. The Supreme Court had ruled in 1994 that mosques were not an integral part of Islamic prayers. In September 2018, the court rejected a plea filed by Muslim groups that wanted the 1994 decision to be referred to a five-judge Constitution bench. The plea said the 1994 decision “had and will have a bearing” on the Ayodhya land dispute case. The rejection of the plea had given the Hindu side hopes of a quick resolution in the land dispute case.

In March this year, the Constitution bench set up a three-member mediation panel—with former Supreme Court judge F.M.I. Kalifulla as chairman and spiritual leader Sri Sri Ravi Shankar and senior advocate Sriram Panchu as members—to look into whether the two sides could reach a settlement. When the panel failed to break the deadlock even after four months, the bench began holding day-to-day hearings in the case in August.

Apparently, it was the longest such hearing held by the Supreme Court since 1973, when it delivered the verdict on the Kesavananda Bharati case after 68 sessions. Last year, the Supreme Court took 38 days to hear the case about the constitutional validity of Aadhaar.

The wait for the Ayodhya verdict will be shorter, but no less difficult. Both the petitioners and respondents, and millions of believers on both the sides, will be keeping their fingers crossed.