For most Kashmiris, the situation has never been as depressing and hopeless as it is now. The revocation of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status has so overwhelmed them with a sense of betrayal and loss that many believe that war is the only way out.

The bottled-up emotions erupted after Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan raised the Kashmir issue in his speech at the UN General Assembly in September. After Khan’s speech, protests broke out across Kashmir and people burst crackers.

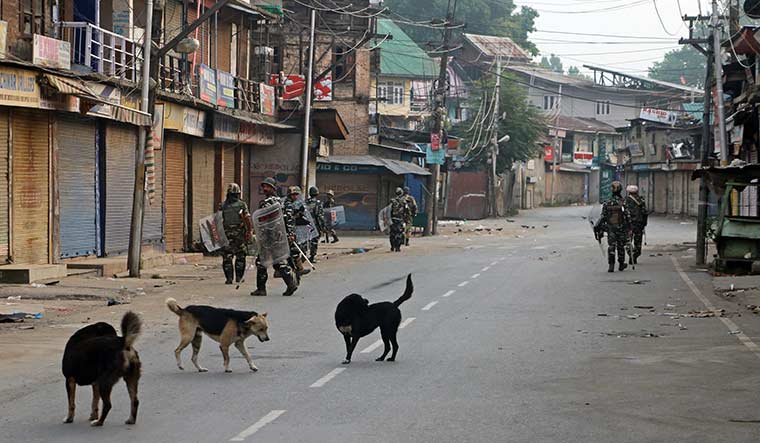

Seven people have been killed in Kashmir since the Union government voided Article 370 on August 5. The lockdown has prevented large-scale protests, except at Soura in Srinagar. Security officials know well that the absence of protests should not be confused with the acquiescence of the people. As Kashmir’s history suggests, the simmering discontent could turn explosive any time.

The closure of schools and businesses after August 5 has morphed into a civil disobedience movement that the government is struggling to defuse. For the first time, supporters of mainstream parties and separatists have found common ground—they feel disempowered and vulnerable, ethnically and politically. The BJP says it has “integrated” Kashmir with the rest of India, but the reality is that the gulf between Kashmir and Delhi has only widened. The party plans to replace the “dynastic and corrupt political elite” in Kashmir with panchayat- and municipal-level leaders. But such leaders are unlikely to fill the political vacuum that exists in Kashmir now.

Most Kashmiris are not convinced by the argument that the ‘integration’ with India will usher in development and improve lives. They point out that states like Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Jharkhand are grappling with poverty and unemployment, even as thousands of people from these states come to Kashmir for work.

Kashmir’s geography and environment do not support large-scale industrialisation. A case in point are the cement factories at Khrew in Pulwama, which ended up polluting saffron fields and affecting people’s health.

Kashmir needs investment in its traditional sectors—tourism, horticulture and handicrafts. Horticulture earns the state Rs8,000 crore a year. The revenue can be multiplied if cold storages and reprocessing plants are set up. Improvements in communication, transport and hospitality sectors can attract high-spending tourists.

The question everyone is asking: How can Kashmir be developed if its people feel disempowered? The BJP’s decision to increase the number of assembly seats in Jammu—from 37 to 43, against 46 in Kashmir—has only reinforced the sense of disempowerment among Kashmiris.

Pandits in peril again

Around 50,000 Kashmiri Pandit families left the state in the 1990s because of militancy. The number of those who remained has steadily declined over the years.

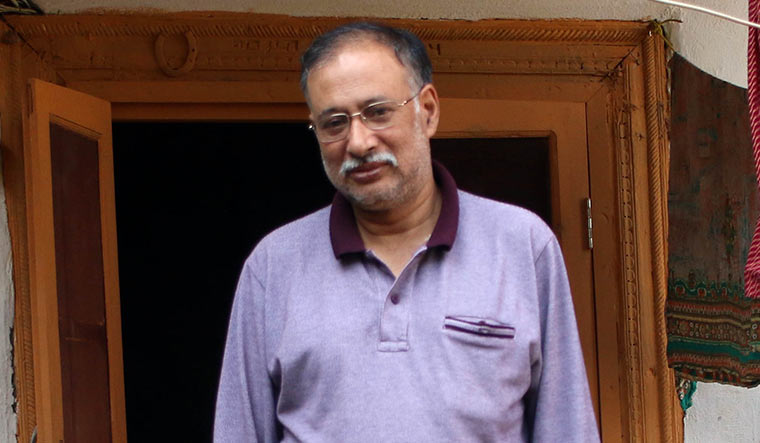

According to Sanjay Tickoo, president of the Kashmiri Pandits Sangharsh Samiti (KPSS), only 2,764 Pandits (808 families) remain in Kashmir. Tickoo, who has emerged as the voice of Pandits in Kashmir, said the voiding of Article 370 would impact their ties with Muslims. “When Kashmiri Pandits like Susheel Pandit and Ashok Pandit speak against Article 370, it has consequences for us,” he told THE WEEK. “We can neither leave Kashmir nor live in peace.”

Tickoo lives at Babarshah in Srinagar. He said after Article 370 was voided, he gave his property documents and children’s certificates to a neighbour for safekeeping. “I had not done this even in the 1990s,” he said. “I don’t fear my neighbours, but I fear strangers.”

He said it would have been reassuring if all 808 Pandit families in Kashmir were living in one area. “People outside Kashmir, including some from our community, are celebrating the revocation of Article 370. But they have no idea what the situation here is like. The government has turned Kashmir into a prison,” Tickoo said.

According to him, India considers only the territory of Kashmir as its integral part. “If the people of Kashmir were also integral to India, then [the government] wouldn’t have taken such a hasty step,” he said.

Pandits in Kashmir are feeling more isolated because of the lockdown. Tickoo said 150 Pandit families that were dependent on jobs in the private sector have suffered. “Muslims receive support from their community through mosques,” he said. “But where will a Kashmiri Pandit go?”

Return of the bunkers

Bunkers were a common sight across Kashmir in the 1990s, when militancy was at its peak. There were bunkers near roads, bridges, highways, schools, colleges, government offices and homes abandoned by Kashmiri Pandits. After the situation improved, most bunkers were removed.

The Central Reserve Police Force has now erected numerous bunkers across Kashmir to tackle militant attacks. It has also put up barricades around Srinagar to seal off the city if needed. Around 78,000 CRPF personnel have been deployed in Kashmir to help the police maintain peace.

CRPF personnel have for years been camping at Bakshi Stadium, Indoor Stadium and Sher-i-Kashmir Cricket Club in Srinagar. There are camps at Karan Nagar, Habba Kadal and Nishat as well. After August 5, CRPF personnel “temporarily” moved into S.P. Higher Secondary School in Srinagar, taking over classrooms, toilets and the auditorium. A teacher said all except two rooms in the administrative block have been occupied by the CRPF. It has also set up two bunkers on the campus.

Five kilometres from the school is Tanghbagh, where two residents, Fayaz Ahmed Gassu and Abdul Rashid Guru, allege that the police are forcing them to convert their homes into CRPF camps. “I will not give my house to the CRPF,” said Gassu. “It’s a very old house and I am making some repairs to make it liveable.”

Guru’s wife is determined to not hand over her house to the CRPF. “Two of my sisters live in the house,” she said. “One is a divorcee and the other is a mute.”

Worried migrants

Days before Article 370 was voided, Amarnath yatris, tourists and students from outside Kashmir began to leave the state. As panic spread, thousands of migrant workers began to leave Kashmir, but a few like Raju Bhai of Gujarat chose to stay.

Bhai’s family is part of a small group of Gujaratis who have, for decades, been living in an old building at Karan Nagar in Srinagar. He sells used clothes. Bhai said he feared for his family’s safety after Gujarati families, including that of his brother Viki, began leaving Kashmir.

“Local people supported me and 15 other families that stayed back,” he said. “I came to Kashmir in my youth. My children and my grandchildren were born here.”

He said he earns Rs200 to Rs300 a day—“enough to buy bread”. His brother and family have returned. “They had temporarily shifted to Tarn Taran in Punjab after August 5,” he said.

As Bhai spoke, a group of women and children gathered. “I have been living here for 50 years,” said Bani, one of the women. Two others, Lakshmi and Ramila, said life in Kashmir was good. “Some of us leave in winter and then return,” said Ramila.

A few migrant workers, especially barbers from Uttar Pradesh’s Bijnor district, have returned. On October 14, militants shot dead S.S. Sagar, a labourer at a brick kiln in Pulwama. Many people in Kashmir say it shows the growing hostility to outsiders.

A tourist paradise in limbo

The lockdown and communication blockade in Kashmir have dealt a blow to tourism. To revive the sector, the government has restored cellphone connectivity and decided to provide internet facilities at tourist spots. Many Kashmiris see the steps as part of the government’s attempt to counter the unofficial shutdown.

A top official in the tourism department said around 17,000 tourists—1,700 of them foreigners—visited Kashmir after August 5. “We are launching a major tourism promotion campaign called ‘Back to the Valley’ to woo tourists,” said the official.

But houseboat owners and hoteliers are not impressed. “Tourists were forcibly evicted from houseboats and asked to leave Kashmir,” said Bashir Ahmed, who owns a shikara (houseboat) at Nehru Park. People like Bashir long for tourists, but do not want to be seen as defying the shutdown.

The hoteliers are in a similar dilemma. An employee of Ahdoos Hotel in Srinagar said the hotel had stopped serving food to the employees of the nearby State Bank of India. The only hotel that has fared well in the past two months in Kashmir is Sarovar Portico in Srinagar, where the government has set up internet facility for journalists. “All of our rooms were rented by reporters from Delhi and elsewhere in August. Then the flow decreased,” said an employee.

Setbacks aside, the hoteliers and shikara owners are hopeful that the tourists will return. “We have seen worse times,” said Bashir.

Tariq Patloo, who owns two houseboats and a resort at Nishat, recalled how houseboat owners in the 1990s scouted for tourists in Delhi and convinced them that Kashmir was safe. “Once, a foreign tourist who wanted to go to Himachal Pradesh was [persuaded to go] to Kashmir,” said Patloo. “When he saw Kashmir, he extended his stay and later visited again.”

Upsetting the applecart

Apple trade has been the unlikely casualty of the Kashmir lockdown. Apple sales earn Jammu and Kashmir Rs8,000 crore a year and provide livelihood to 33 lakh people, including seven lakh farmers. Around 75 per cent of apples that India exports are grown in Kashmir.

Many apple growers have been struggling to sell their produce as the fruit market at Sopore in Baramulla, Asia’s second largest, remained shut. The unofficial shutdown has compounded their problems. Three apple growers and a two-year-old girl were injured in Sopore when militants fired at them for defying the shutdown.

The government decided to buy apples directly from the growers, but only 3,000 farmers had signed up by the end of September. “To elicit a better response, we have proposed a hike in the purchase price for all grades of apple,” said a senior official at the department of horticulture planning and marketing.

The fact that they had received money in advance from non-Kashmiri buyers prevented many apple growers from selling their produce to the government. “We will sell our crop directly at rates better than what the government is offering,” said Adil Hussain, a farmer.

Ghulam Muhammad of Sopore is one of the farmers who have decided to sell their produce to the government. “Given the situation in Kashmir, it is a safe bet,” he said.

The communication blockade made it impossible for growers to contact buyers outside the state or to keep track of the trucks carrying their produce to Delhi and elsewhere. Horticulturalists say proper grading of apples will ensure better returns. Earnings can also be increased if facilities to produce jams, juices and other products are set up in Kashmir.

For now, the apple trade is bearing the brunt of the anger in Kashmir. On October 14, militants shot dead Sharief Khan, a truck driver from Rajasthan who had come to transport apples from Shopian. Three days later, militants opened fire at Charanjit Singh and Sanjiv Kumar, an apple trader and a labourer from Punjab, at Traz in Shopian. Singh died on the way to the hospital, while Kumar is recuperating at SMHS Hospital in Srinagar.

The art of living

A question that often baffles outsiders is how Kashmiris survive prolonged disruptions and lockdowns. A short answer: resilience and adaptability.

Kashmir has more than 70 lakh people. About half of them earn their livelihoods from the apple trade, while the other half is largely dependent on tourism, business and government jobs. Of the five lakh government employees in the state, more than half live in Kashmir. Since the 1990s, governments in both Jammu and Kashmir and at the Centre have viewed government jobs as an effective counter to militancy. The rise of militancy is also the main reason that the police have recruited more than one lakh people in the last three decades.

A few good seasons do help hoteliers and houseboat owners weather sudden disruptions. When militancy was at its peak, many traders set up businesses outside Kashmir. These businesses have been helping them survive difficult times. Disruptions largely affect those working in the tourism sector, pharmaceutical and insurance companies, and malls and restaurants.

Markets in Kashmir now open at dawn and close at 10am. A strong network of baitul maal (Islamic charities) collects funds from the affluent to help the needy. They also help the poor during medical emergencies.

Troubled minds

The turmoil has taken a toll on the mental health of Kashmiris. According to a 2015 survey by Medecins Sans Frontieres, 45 per cent of the adult population in Kashmir showed symptoms of mental distress, 41 per cent showed signs of depression, 26 per cent showed signs of anxiety and 19 per cent had probable symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Mental health expert Dr Arshid Hussain said it would take time to assess the impact of the recent lockdown. “The youth of Kashmir used to gather on social media and connect with each other,” he said. “This space has been choked.”

Doctors in Srinagar said the lockdown resulted in a rise in the number of patients suffering from anxiety attacks. Also, an increasing number of people are purchasing medicines without prescription. The last time a similar trend was witnessed in Kashmir was in the 1990s, when killings, torture and custodial deaths had become routine.

The doomed mainstream

More than two months since the lockdown began, former chief ministers Farooq Abdullah and Omar Abdullah of the National Conference and Mehbooba Mufti of the Peoples Democratic Party continue to be in detention. The government, however, has decided to hold elections to the block development councils in the state, ignoring the prevailing vacuum in mainstream politics.

The NC, the PDP and the Congress have decided not to contest the polls. But, in the emerging political reality, the Abdullahs and the Muftis are faced with a difficult choice: accept the new reality or prepare for a long struggle.

“We will not budge. Farooq sahab is determined to fight it out,” said Hasnain Masoodi, NC leader and Anantnag MP.

Mehbooba’s daughter Iltija Mufti said her mother believed that the people’s rights were far bigger than her personal freedom. “She was told that she would be released if she signs a bond promising to keep quiet. But she refused,” Iltija told THE WEEK.

Sources say the Centre is working to convince the NC leadership that all is not lost, and that the two sides can work out a deal. The government, however, has made one thing clear: There is no going back on the voiding of Article 370.

The big cogs in the machine

Five officials have emerged as the face of the Jammu and Kashmir administration—principal secretary Rohit Kansal, development commissioner of Srinagar Shahid Choudhary, senior superintendent of police (security) Imtiyaz Hussain, information and public relations director Syed Sehrish Asgar, additional director-general of police Munir Khan and his brother and divisional commissioner Baseer Khan.

Kansal, Asgar and Munir Khan had been regularly briefing journalists since August 5. When media reports indicated a siege-like situation in Kashmir, Hussain uploaded videos of normal traffic on roads in Kashmir. He also criticised Imran Khan’s speech at the UN.

Choudhary said the administration had fared well. “We ensured supplies to the people and availability of 95 per cent of doctors in hospitals,” he said. “We made 300 vehicles available to students travelling in and outside Kashmir to take exams.”

Choudhary said he worked 18 hours a day from August 5 to September 18. “We provided support to 15,000 tourists, including 1,700 foreigners who arrived in Kashmir after August 5,” he said.

Munir Khan said “small incidents” were tackled locally. “Our worry was that our neighbour might instigate people, leading to bloodshed,” he said. “Thank God they didn’t succeed. Because of it, cellphones are back.”

The yearning for war

Days after the voiding of Article 370, discussions raged in Kashmir about what was in store for the people. Many felt militants would get more recruits, while others said a sustained agitation would force the Centre to reconsider the decision. There is also talk about how a war between India and Pakistan could help bring international intervention.

Political analysts say the feeling that war is the only way out shows the level of unease among the people. “This reflects how humiliated and desperate the people are feeling because of the removal of Article 370,” said political scientist Noor Muhammad Baba. More disconcerting, according to observers, is the arbitrary manner in which the article was voided.

Baba believes war is hardly a solution, as it would only create more problems. “There is anarchy in Kashmir, as there is no leadership,” he said. “[To yearn for war] is not reasonable, but in desperate situations, people do commit suicide.”